‘Here are many and boundless marvels; in this First India begins another world.’

Jordanus Catalani, the first bishop of the Church of Rome in India, introduced the northern part of the subcontinent to his readers in fourteenth-century Europe in this manner. Two hundred years before the advent of Vasco da Gama, Western Christianity had already arrived in India, finding among its diverse people and faiths the Church of the East at home since the beginning of Christianity.

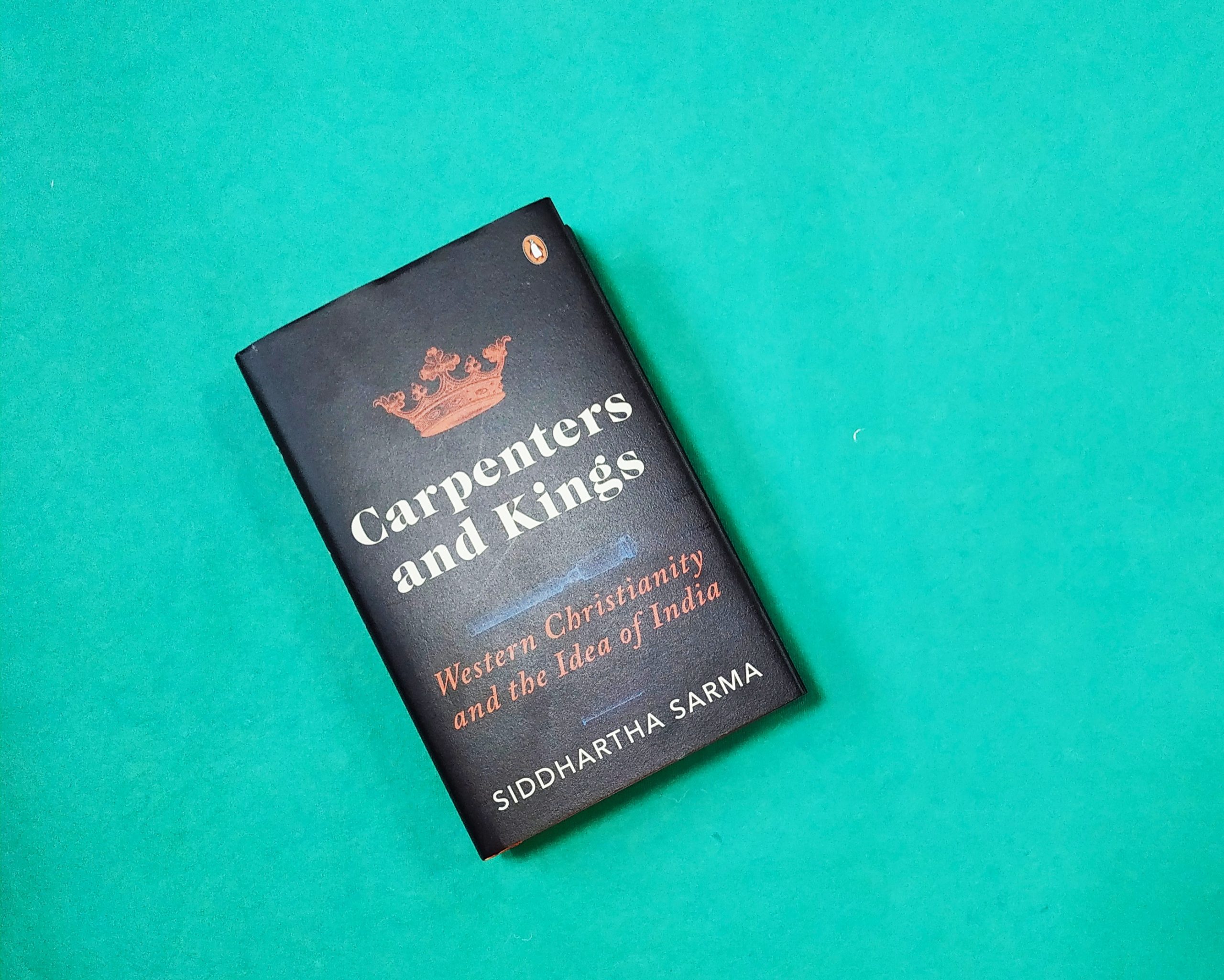

Siddhartha Sarma’s gripping narrative traces the cross-cultural trade of Antiquity which established the roots for the spread of Christianity in the Apostolic Age, across the intervening centuries to the alliance of Roman Catholic Church and the Portuguese crown which pursued an imperial policy.

Carpenters and Kings is a tale of Christianity and, equally, a glimpse of the India which has always existed: a multicultural land where every faith has found a home through the centuries.

The presence of Jewish communities in the western coastal region of India went back to the Achaemenid Persian Empire.

The first Jewish communities in India are likely to have established themselves in coastal cities in the north-west around the beginning of the fifth century BCE, during the expansion of the Achaemenid Persian Empire. Eventually, Jewish diasporic groups would settle along the Konkan, Malabar and Coromandel coasts. These, the oldest of India’s Jewish communities, are known as the Cochin Jews. But there have been others down the centuries, particularly after the formation of the Jewish diaspora following the destruction of the Second Temple in Jerusalem by the Roman Empire in 70 CE.

The Acts of Thomas, which was considered Scripture by early Christians of both Asia and Europe, describe the miracles of the apostle Thomas in India.

‘Send me where you want, but send me somewhere else. Not to India.’ Thus begins The Acts of Thomas, an account of the coming of the apostle Thomas to the subcontinent. Tasked with spreading the word of Christ among the Indians, a reluctant Thomas is finally compelled to travel to the subcontinent as a carpenter. In India, according to The Acts, he preaches among the people, heals the sick and converts royal families before being martyred. While not an account of history, The Acts does convey an idea of how Jews, Christians and other people of West Asia thought of the polytheistic Indians in that early period of Christianity. India was therefore a vital part of the early Christian imagination of the known world.

The slow spread of Christianity among Jewish communities in India in the Apostolic Age itself.

By the end of the Apostolic Age, Christianity had spread among Jewish communities and Gentiles in Greece and other parts of the Roman Empire including the Italian Peninsula and Egypt, besides Persia and north-western India, but perhaps no farther than the coastal areas of the subcontinent. As the ecclesiastical structures to minister to these communities grew, it would have been difficult for smaller communities of Christians in the interiors of India to be closely connected to centres like Edessa in Mesopotamia, where The Acts of Thomas was written and where the remains of the apostle found a final resting place. In coastal India, the first Christians were almost certainly converts from Judaism. There might not even have been a conscious break from the religion of their ancestors. Conversion by Indian Jews to Christianity at that point would have been part of internal religious reform within Jewish communities, led by baptizing cults. This happened in the Middle-East in that period as well.

The famed tale of the Christian prince Josaphat and his conversion by the hermit Barlaam, appears to be based on the tale of the Buddha.

Jataka stories percolated from India to the Sassanid Persian Empire in the sixth century CE. By the 11th century, these stories had circulated in Europe, where eminent personages of the Church and ordinary Christians believed that Prince Josaphat, based on the prince who became the Buddha, had been a Christian. The tale of Josaphat and the supposedly Christian monk Barlaam became one of the first bestsellers of the age of printing, with editions of the legend selling more copies than the Bible. Barlaam and Josaphat became the most famous and lauded Indians in Europe in the Middle Ages and were canonized by both the Latin and Greek Churches. By the time the Portuguese arrived in India, there was a great deal of curiosity about what the Indians thought of the two men.

The author of The Christian Topography, Cosmas ‘Indicopleustes’ found thriving Christian communities in Konkan and Malabar in the sixth century.

Cosmas’s reputation among later scholars was so indelibly tied with his visit to India that he became known as ‘Indicopleustes’, the sailor to India. The old ports of India were as vibrant as ever, and there was still a vast market for western goods. Sailing south from Bharuch, Cosmas arrived at the town of Kalyan where he found a resident Christian community with a bishop ordained and sent from Persia. Syrian Christians had a well-entrenched ecclesiastical order in the coastal cities of northern Konkan. In ‘the country of Male’, that is the Malabar Coast, Cosmas found both pepper and a church of respectable size. He also found an established Christian community in Sri Lanka.

Tibetan Buddhist texts dating from the eighth to the ninth centuries mention ‘Jesus the Messiah’.

At the beginning of the twentieth century, a sealed cave in the region of Dunhuang in western China was found to contain a treasure trove of Tibetan manuscripts from the fifth to the eleventh centuries, which reveal the impact of Nestorian Christianity on Tibetan Buddhism. One of the manuscripts, dated from the late eighth to the early ninth centuries, tells the reader to prepare for the End of Days, when ‘the god known as Jesus the Messiah, who acts as Vajrapani and Sakyamuni’ will return. This ‘judge who sits at the right hand of God’ will arrive and teach yoga to believers, who are told not to fear any demons or malevolent spirits. For Tibetan Buddhists of this period, Christ was supposed to return and fulfill the functions of Buddha Maitreya during the End Times.

The writings of Giovanni of Montecorvino have extensive notes on the Deccan and on the existing Christian communities.

In 1291, Giovanni of Montecorvino, a Franciscan friar, was directed to travel to the East from Persia. Starting from the city of Tabriz, Giovanni travelled to the Persian coast and then by sea to India, where he formally established the Latin Church. Giovanni spent thirteen months in India preaching among Syrian Christians, whom he found in abundance along the western coast, and the Hindus. He spoke of his favourable impressions of the land and the people.

The strange case of the Four Martyrs of Thane, the most well-known historical Christian martyrs in India in the Middle Ages, also shows how the first Western Christian travellers to India came in contact with the resident Syrian Christians.

Three Franciscan monks and a lay European, Demetrius, arrived in India in 1317 and were hosted by the Syrian Christian community of Thane. The man at whose house the Franciscans were staying beat up his wife after a domestic quarrel. The woman complained to the local Muslim judge or ‘qadi’ against her husband and added that she had four male witnesses to the crime, monks from Persia. The qadi called for the Franciscans and Demetrius. The hearing then seems to have digressed into a religious debate between the qadi and other learned men present there, and the Franciscans. The qadi asked them what their view was of the Prophet, at which Thomas, one of the Franciscans, made some derogatory remarks against him. The court declared them guilty of blasphemy and they were sentenced to death.

The writings of Jordanus Catalani, a Dominican friar from southern France which describe a largely tolerant Hindu society.

Jordanus, who originally arrived in India with the Franciscans who were martyred, spent more than a decade afterwards travelling in western and southern India. From his travels emerged the Mirabilia Descripta, the most detailed and scholarly account of India by a European in the Middle Ages. He found the Hindus welcoming towards Christian missionaries and never feared for his safety while preaching among them. In fact, missionaries would be treated with warmth and respect by Hindus across the land, and their safety would be ensured. Whenever a Hindu chose to be baptized, the people or the authorities would not create any hindrance or persecute either the convert or the missionary. This freedom, said the Dominican, was common to Hindu and Mongol societies and among other people east of Persia in his time. Jordanus met Indian Christians and discovered the deep roots of the Church of the East in the subcontinent. He would eventually be ordained the first bishop of the Church of Rome in India, with his seat at Kollam in what is Kerala today. Over the remainder of the 14th century, dozens of Christian monks and scholars travelled to India or through the subcontinent on their way to China, and wrote about Indian society.

The Papal Bull of Pope Nicholas V seemed to have considered India as a Christian nation prior to the Portuguese arrival in Kozhikode and the beginning of European colonialism.

In 1454, Nicholas issued a second bull, the Romanus Pontifex, which expanded on the earlier Dum Diversas. The Portuguese were charged with exploring the seas and finding a route to India, ‘whose people are said to worship Christ’, and to convince the Indians to join an alliance with Europe against the Muslims. Nicholas and his advisers seem to have completely misread Church history on the situation in India, and assumed that Indians were mostly Christian.

Get your copy of Carpenters and Kings today!