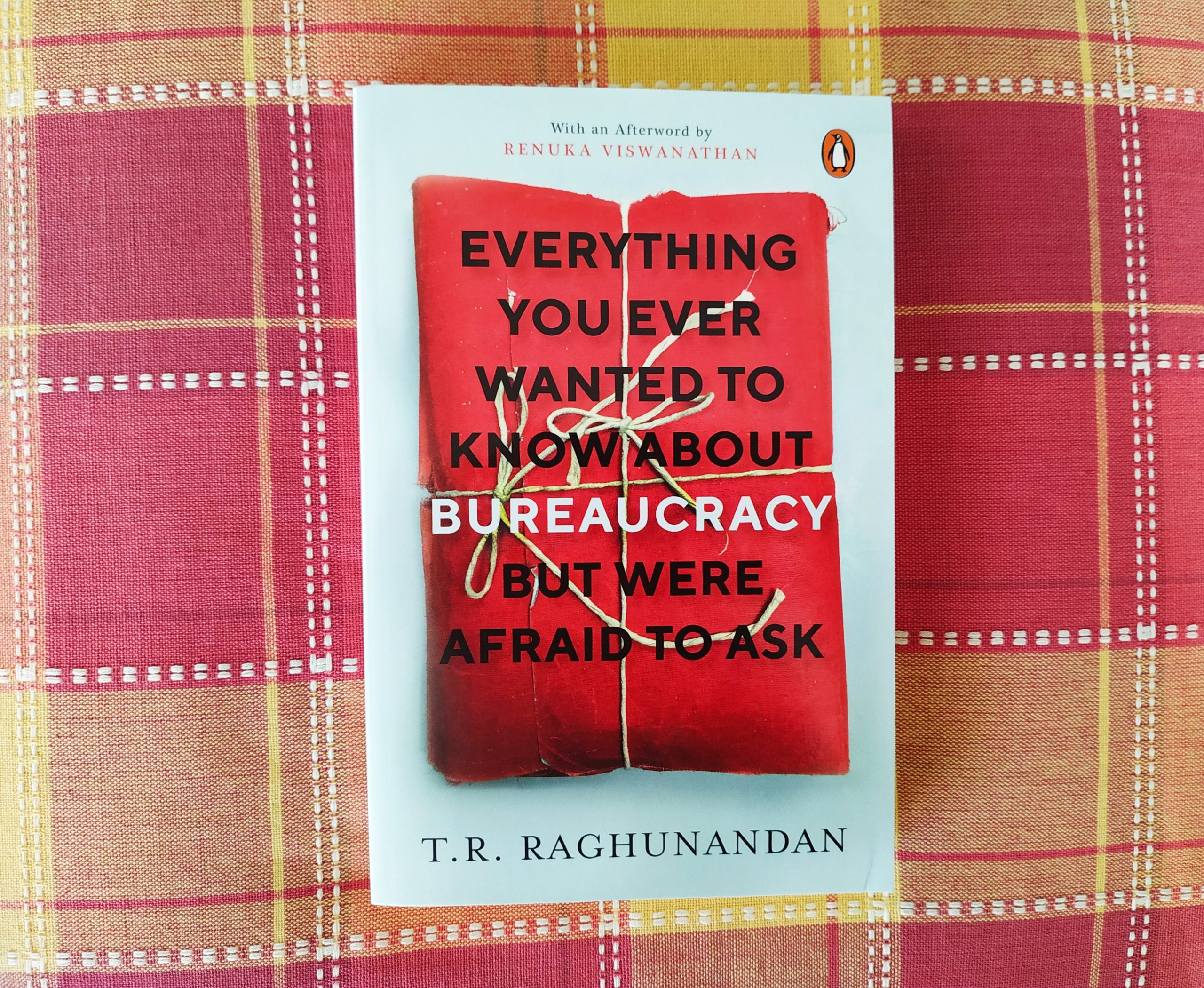

The aura of the Indian Administrative Service has remained intact over the years. In this humorous, practical book, T.R. Raghunandan aims to deconstruct the structure of the bureaucracy and how it functions, for the understanding of the common person and replaces the anxiety that people feel when they step into a government office with a healthy dollop of irreverence.

Here are a few things you didn’t know about the Indian bureaucracy!

Although higher civil services were in theory open to women since Independence, the first women officers who joined the government (Chonira Belliappa Muthamma to the foreign service in 1948 and Anna George to the administrative service in 1951) were inducted with reluctance and with the caveat that they must leave if they ever married. At that time, patriarchal and misogynistic ideas about the unsuitability of women at higher official levels were widely prevalent among colleagues, bosses and members of the public.

The first woman to top the IAS list was Anuradha Majumdar in 1970, the year in which a record number of women became civil servants.

The government is stubbornly loyal to the paper file. Unless a government office is buried under paper, preferably with fetid odour, it does not look and feel like a government office.

The blunt fact of the matter is that the bureaucracy, and particularly the IAS, is inherently suspicious of and, therefore, resistant to changes that introduce imponderables into the way the officers’ careers progress.

In an earlier era, the idea that an IAS officer should be a generalist had the makings of a It was considered bad form for an IAS officer to quote an educational degree in a particular subject to seek a posting in a related department; indeed, it was bad form for an officer to ever ask for a post.

There is no doubt that one of the significant reasons why India is progressing is because there are large numbers of honest bureaucrats, who go about their work diligently and honestly, but are constrained not to speak about the changes they have brought about, because they are trained to be self-effacing.

IAS officers are sticklers for detail. They need to find out quickly as to whether the individual opposite them are (a) senior or (b) junior to them and/or whether they are (c) direct recruits or (d) promotees into the service. The nub of the matter is to find out the status and seniority of the other. A miscalculation of seniority in that introductory meeting can result in the destruction of one’s confidential reports. It is prudent for the ambitious officer to err on the side of caution and address any object that looks senior to her, animate or inanimate, as ‘Sir’ or ‘Madam’.

Everything You Ever Wanted to Know about Bureaucracy But Were Afraid to Ask tells you all about the fast-tracked elite civil servant, who belongs to a group of generalist and specialized services selected through a competitive examination