Hi there!

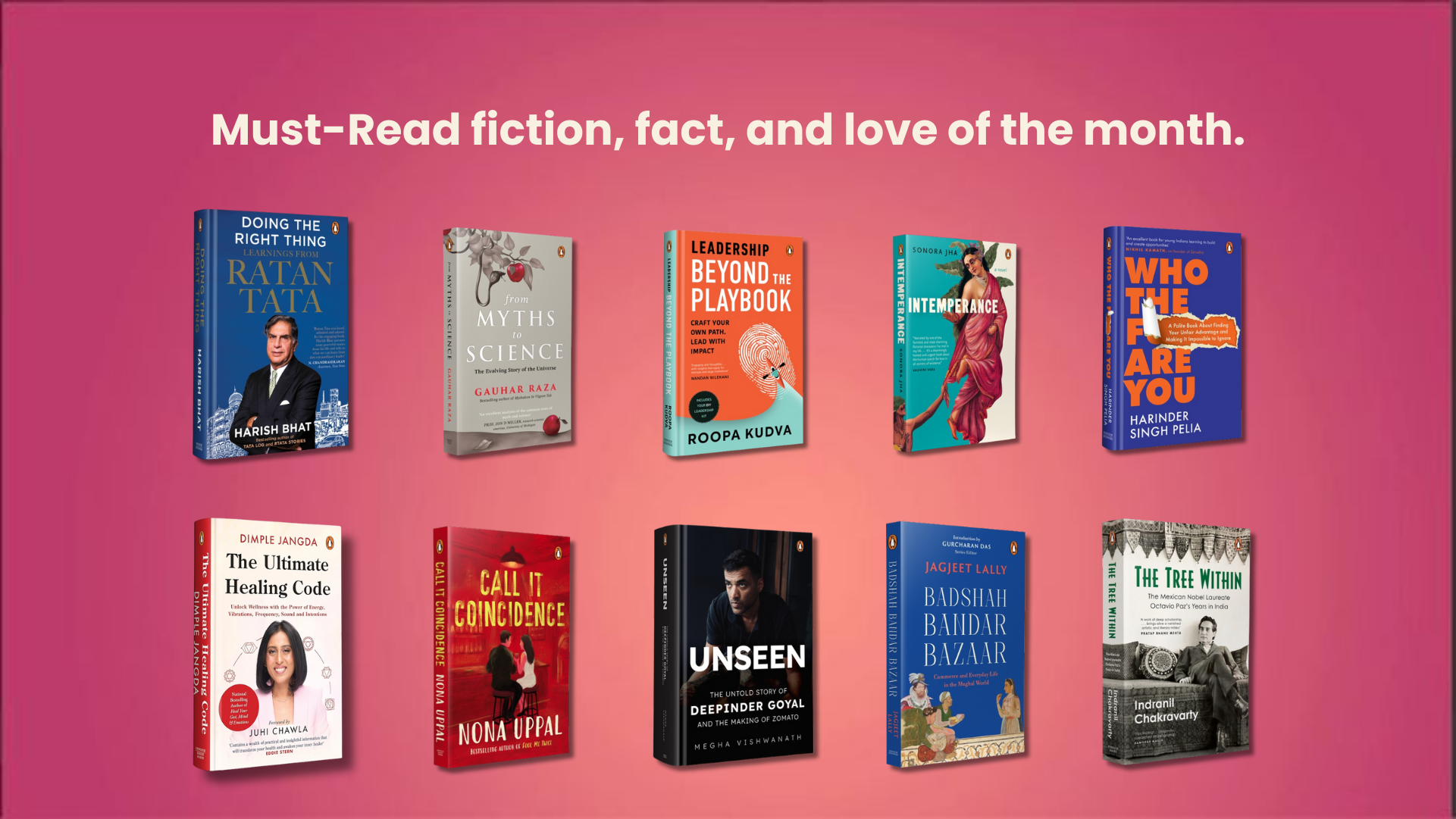

Greeting the shortest month of the year with eyes full of hope, hearts brimming with joy, and books from all spheres of life.

February is a month that often asks us to look inward, and our new releases are here to guide the way. From the intimate reflections of Bloom and Queerly Beloved to the sweeping generational sagas in This is Where the Serpent Lives, our latest shelf is an exploration of the human heart in all its forms. Whether you’re navigating the complexities of modern relationships in What They Don’t Tell You About Marriage or finding stillness in From Chaos to Clarity, these books offer a home for every reader.

Ready to dive in?

Discovery of New India – Aakar Patel

Journalist Aakar Patel guides readers through a unique graphic novel examining ‘New India’s’ grand claims versus ground realities. Through conversations, history, and true stories, this witty political primer unpacks how government decisions shape our freedom, safety, prosperity, and health.

From Chaos to Clarity – Shonali Sabherwal

Strategies for Cancer Prevention and Remission Acclaimed nutritionist Shonali Sabherwal offers hope for those affected by cancer. This essential guide provides detox plans, nutritious recipes, and holistic dietary strategies for prevention, remission, and treatment phases—empowering readers with practical advice during life’s toughest battles.

Half of Forever – Ravinder Singh

What if forever isn’t measured in time, but depth? Ravin and Heer’s chance meetings grow into unintended love but at a heavy cost. Ravinder Singh’s reflection on transformative love quietly closes his trilogy following I Too Had a Love Story.

Queerly Beloved – Farhad J Dadyburjor

Ved Mehra and Carlos Silva plan their big fat Indian wedding, but complications mount: his mother’s smitten, his father’s secret surfaces, and his ex returns. Farhad J Dadyburjor’s sparkling romcom celebrates love in all its messy, complicated glory.

What They Don’t Tell You About Marriage – Yashodhara Lal

Couples therapist Yashodhara Lal reveals the real work after the honeymoon. Drawing on clinical experience and her two-decade marriage, she normalizes conflict and offers practical tools for managing differences, money, sex, in-laws, parenting, and betrayal with clarity.

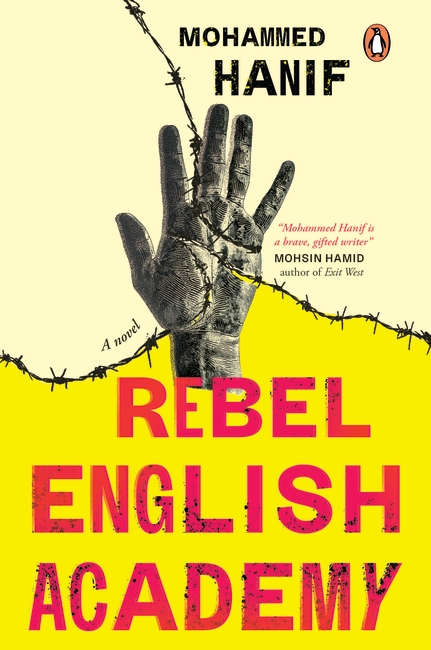

Rebel English Academy – Mohammed Hanif

After a political execution, OK Town erupts. At the Rebel English Academy, refugee Sabiha arrives with a gun and secrets. Meanwhile, disgraced Captain Gul hunts protesters. Mohammed Hanif’s wry, searing novel explores political power, religion, sexuality, and dissent in modern Pakistan.

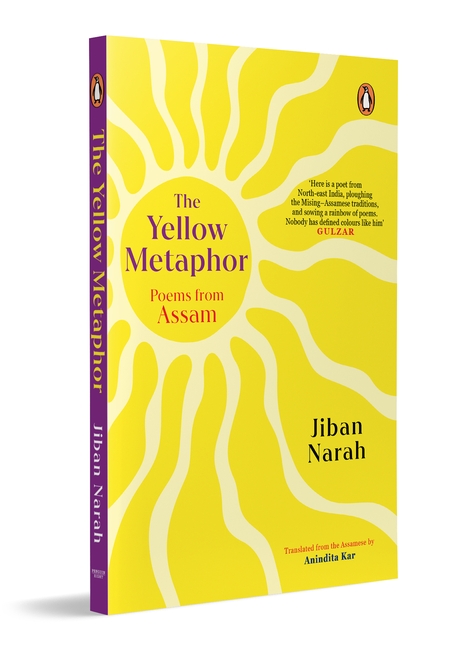

The Yellow Metaphor – Jiban Narah

99 Selected Poems: 1990–2023 Three decades of Jiban Narah’s shimmering poetry from Assam and India’s North-east. Steeped in Mising and Assamese lore, his verses carry the Brahmaputra’s memory, displacement’s ache, and quiet rebellions—translated luminously by Anindita Kar into incandescent, metaphor-rich reflections.

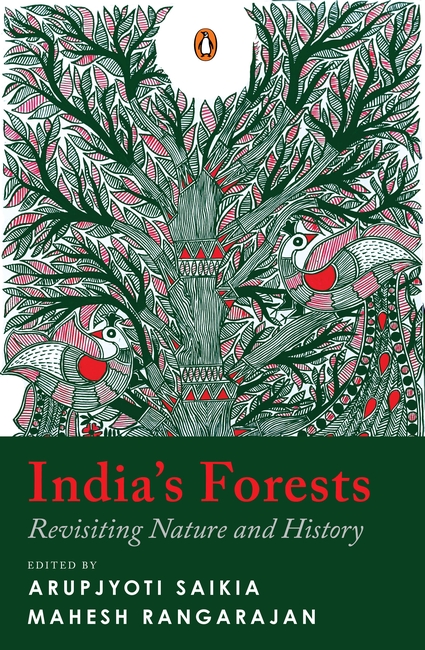

India’s Forests – Arupjyoti Saikia, Mahesh Rangarajan

Leading scholars reappraise Indian forests as living, contested spaces shaped by power, culture, and society. Spanning prehistory to present, this volume examines forests as ecological lifelines and sites of legend, memory, and scientific knowledge—asking fundamental questions about their fate.

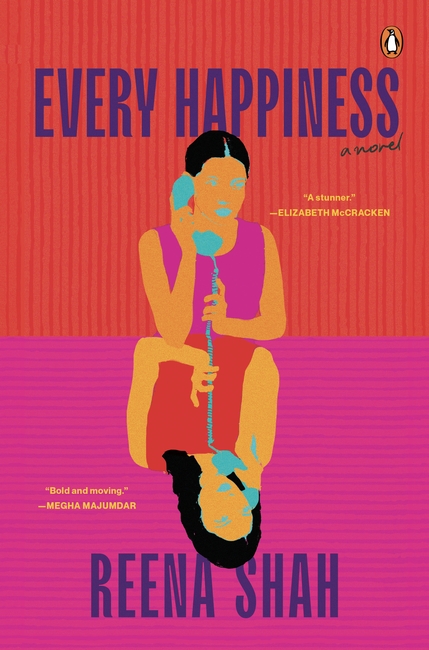

Every Happiness – Reena Shah

Deepa and Ruchi’s swift childhood friendship follows them from India to Connecticut suburbs. As class disparity, family needs, and desire test their bond, a dangerous secret about wealth forces both women to weigh loyalty against survival in their burgeoning Indian American community.

This Is Where the Serpent Lives – Daniyal Mueenuddin

From Pakistan’s chaotic cities to lawless countryside, Daniyal Mueenuddin follows interconnected characters struggling between moral paths and worldly survival within systems of caste, capital, and social power. Intimate and epic, this tour de force destined to become a contemporary classic.

Hot Butter Cuttlefish – Ashok Ferrey

Personal trainer Malik relocates to sleepy Kalabola village when COVID strikes. In Ashok Ferrey’s deliciously dark Sri Lankan romantic comedy, lines blur between hero and villain, love arrives in strange disguises, politics get personal, and Karma may be the true leading lady.

Bloom – Aisha Sharma

Aisha Sharma explores the delicate balance between resilience and vulnerability. Through intimate reflections, Bloom guides readers toward self-compassion, celebrating the quiet power found in embracing both our strength and softness on the journey to authentic self-love and personal growth.

Vikram and Betaal – Night of The Blood Mood – Amit Juneja

Silicon Valley entrepreneur Vikram abandons everything when his wife faces terminal cancer. A desperate bargain with a mysterious priest binds him to capture the ancient pishach Betaal. Amit Juneja’s haunting tale explores where ancient folklore collides with modern reason, testing love’s limits.

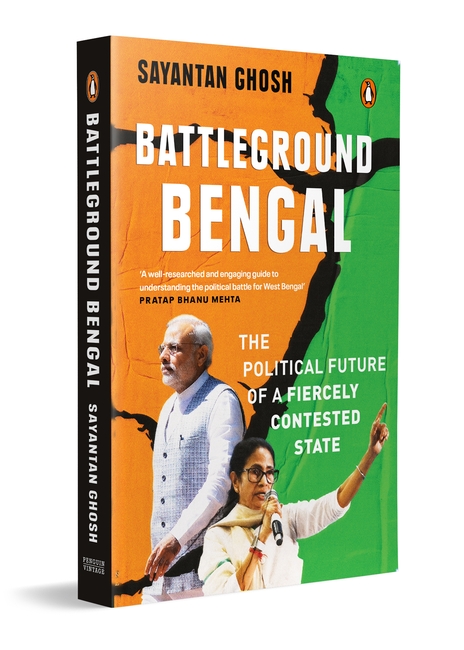

Battleground Bengal – Sayantan Ghosh

Once a Left bastion, West Bengal has been TMC-dominated for over a decade. But the BJP is rising. Through archival documents, electoral data, and field reporting, Sayantan Ghosh analyzes identity, patronage, and fear shaping Bengal’s politics ahead of 2026’s crucial assembly election.

Winning People Without Losing Yourself – Ankur Warikoo

This collection of sharp, lived truths reveals how people behave, why, and how to respond with clarity instead of chaos. One page, one insight—a practical guide for dealing with people without exhaustion.

Evolve – Debashis Sarkar

49 Counterintuitive Principles for Business Could intuition create blind spots? Debashis Sarkar explores counterintuitive thinking—questioning assumptions and embracing strange strategies. Drawing from psychology, economics, philosophy, and technology, this result-oriented toolkit offers research-backed principles for unlocking hidden opportunities and competitive edges through innovation.

Unruly – Upasana Sarraju

Prize-winning research that makes you laugh first, think later. Funny, unhinged, and quietly radical, this love letter celebrates weird science, weirder scientists, and stubborn curiosity.

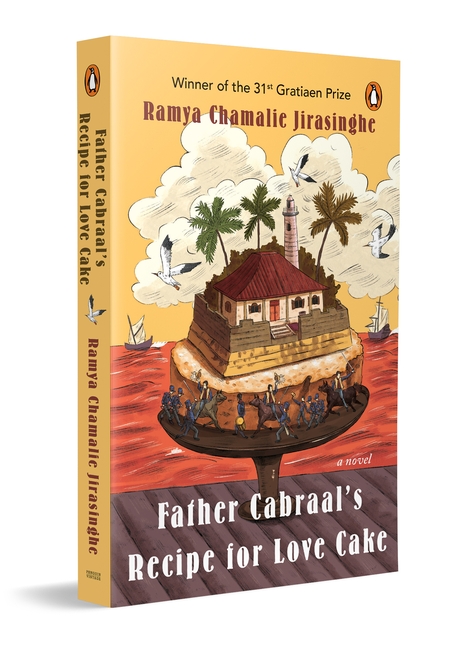

Father Cabraal’s Recipe for Love Cake – Ramya Chamalie Jirasinghe

In the 21st century, former war reporter Katharina shelters a fugitive while baking cakes from an old recipe. In the 17th century, Santiago defies The Company by marrying local pepper farmer Maria. Ramya Chamalie Jirasinghe explores colonial exploitation’s complex legacies.

The Manifestation Mindset – Vrindda Bhatt

Everything you want is within reach—master the mindset to claim it. Vrindda Bhatt’s science-backed guide moves beyond wishful thinking to grounded transformation. Through practical exercises covering health, relationships, money, and career, readers learn to train their minds for purposeful, fulfilling action.

Happy Reading!