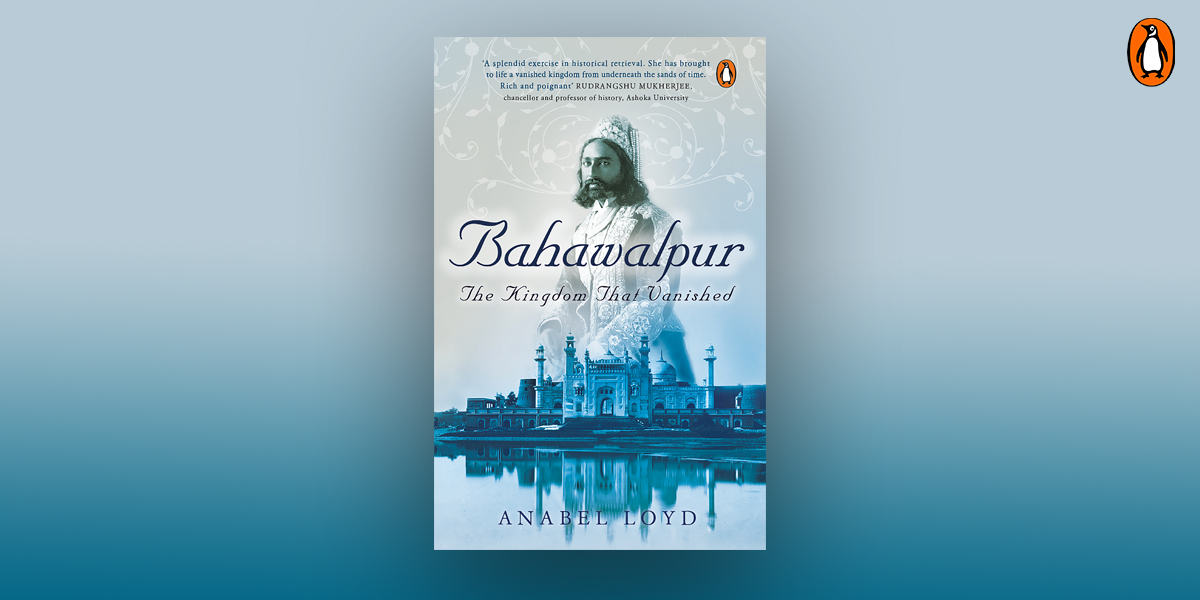

In the seventy or so years since Independence, much less has been written about the Princely States which acceded to Pakistan than those that remained in India. The name of the once great State of Bahawalpur is no longer remembered among its well-mapped peers over the border in Rajasthan.

Bahawalpur is a series of conversations between the author, Anabel Loyd and Salahuddin Abbasi, amir of Bahawalpur and the son of the erstwhile Nawab of Bahawalpur. The latter reminisces about his family and sheds light on Bahawalpur’s princes through old records, letters etc.

The book begins with a quote from Shakespeare’s infamous play, The Tempest, ‘What’s past is prologue’. This means that the past is a preface to the future – we cannot forget the lessons of history. As Salahuddin Abbasi takes you back, you can’t help but draw parallels between the long forgotten princely state of Bahawalpur of the past and the Pakistan of the present.

Jinnah’s aspirations for nationality and not communality- buried

Jinnah’s vision of a country had been buried, over time- not only under the flow of patronage and corruption but also under the illusion and imperative, the ‘mirage’, of the Islamic state.

The sheer one-upmanship of the everyday, increasingly archaic, public practice of religion in Pakistan hinders the running of a contemporary progressive state and argues an almost impossible case for reinstatement of Jinnah’s aspirations for nationality rather than communality.

While the state promises Jannat to the poor, the young do dream of a better existence

Pakistan is more than ever girt with the restraints of caste, creed and class, but young people continue to dream of something better and of levelling the ground. Those living in extreme poverty may be easily seduced or coerced by the promises of extreme Islam: a glorious life to come after death providing some sort of solace or reward for the lack of any uplift through education or public services during the only earthly existence available to them.

The partition may have given us hindsight…

Pakistan looks backwards for religious authenticity, to a dream of national identity and unity never fulfilled after Partition which tore the country from its past.

But Pakistan no longer looks back far enough to its extraordinary history as part of a greater whole. That pas was cast into the deep chasm of Partition.

…But what about foresight?

Nowadays the country often appears neither to look back nor forwards beyond the trappings of new infrastructure in transport systems, shopping malls and increased urbanization. Such changes leave the poor exactly where they have always been, with nothing, and, regardless of the blandishments of government, does little to encourage outsiders to come in.

The wealthy get enmeshed in the threads of corruption and nepotism while trying to rise above it

Education abroad seems to have become a standard for those who have inherited status or have gained vast new wealth. Not all are lured for long by migration for the sake of further fortune. Those who return are entrepreneurial, creative and determined to find ways to circumvent or rise above endemic corruption in order to move forward. However, they may already be enmeshed in the threads of nepotism and corruption by virtue of the endless unbreakable network of familial connections at the top of Pakistani politics and society.

Anyone with a penchant for history and politics would definitely consider Bahawalpur an insightful read. Read it and tell us what you think?