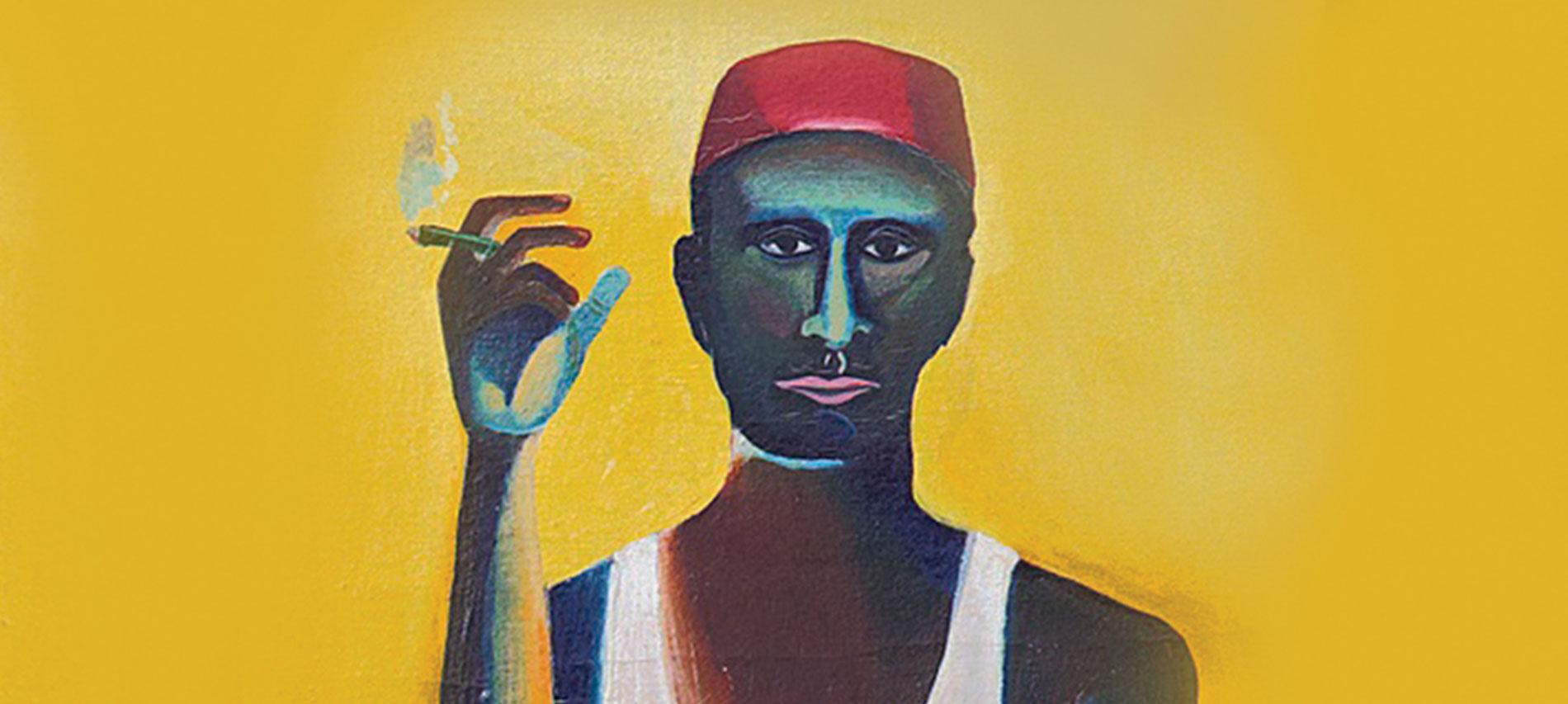

Anjum Hasan is the author of two critically acclaimed novels- Lunatic in my Head that was shortlisted for the Crossword Book Award and Neti Neti, shortlisted for the Hindi Best Fiction Award. She has also written the short fiction collection Difficult Pleasures along with a book of poems titled Street on the Hill. Currently, she is the Books Editor at Caravan Magazine. In her latest book, A Day in the Life, Hasan gives us fourteen well-crafted short stories that provide an insight into the daily life of her characters. With protagonists like a non-conformist living by choice in a small town or a middle class woman’s bond with her maid. Hasan shows that there is an unusual charm in normal, everyday life too.

Let’s read an excerpt from the short story The Stranger from Hasan’s latest book- A Day in the Life.

______________________________________________________________________

There were no new ideas to be found in the city so I retired last year to this small town—an experiment to see if I could live in a house with a tiled roof that sometimes leaked and little storybook windows that muffled rather than let in light. Four months straight it rained with pounding urgency, bookended by two of drizzle. Sentences that I thought had no currency any more, not in the twenty-first century, still applied here, in this drenched hill town. It was a dark and stormy night. Or, The wind howled in the trees and loudly rattled the windowpanes.

One could imagine a very old place, a sparser and hardier monsoon existence hidden in the folds of the green valleys, even though they’d been killing off the vestiges in recent years— building hotels over the Christian graveyards and glassy shopping complexes where there’d been trees and empty space. Still, a few bungalows with compounds and driveways from a hundred years ago remained, and in the bazaar lots of those crooked little two -storey split-level shophouses with wooden casements, which too must have been here at least since the British, were writing in their gazetteers about who was up to exactly what business in the district. With the rain and the daily power-cuts, the Gothic mist creeping over everything all the time in season and the silence that lay over the hedgerows in the lanes away from the town centre, this was still a place where you could play at being someone else.

I’d seemed to be coasting along like everyone else in the city but was really eyeing something deeper—a love affair or a glittering friendship. I was lonely and didn’t see it. When this hit me, when I turned forty, then forty-five, and still felt unmade and unresolved, still chasing something just around the corner, I stopped. I had some money from two decades in the industry—if not scaling the heights of the corporate ladder, then not sliding down it either. Enough to ride on for a few years if I yielded all ambition, so that’s what I decided to do. Become nobody or, at least, a sincerely regular man. Cease thinking I was going to get anywhere either in the realm of intellectual achievement or human relations.

What can better aid coming down to earth than a half-forgotten small town: that stained suburban air, the permanent emanations of open sewers and busy bakeries? A whole population’s worth of people with reduced hopes, happy to cut their coats according to their cloth.

I’ve been here almost a year now, one monsoon to the next, and I have a house of three small rooms which is too big for me, a talkative cook in a burka and a target of getting through all the mouldy books in the back rows of the local library, which no one seems to have touched since circa Independence. I do try to give some kind of shape to my days—watching the blackbirds with my morning coffee; walking with the late afternoon sun when there is one; helping, because I was inveigled into it, the landlord’s middle-school-going boy and girl with their homework; just sitting around reading in the evenings as I drink brandy with hot water, or bad wine, or whisky with ice on summer nights when it’s really warm and I’m feeling like I might start to be sorry for myself. Who was it who said Proust’s pinings and dissatisfaction represented the illness of the cultivated classes in a capitalistic society? I’m trying, with the benevolent aid of my neighbourhood liquor store, to undo my cultivation and sometimes casting off these chains can hurt.

I wake up in the dark: it could be 4 a.m. or well past seven. The clacking rhythm of rain on the roof seems to be saying, I’m here to stay. Okay, I tell it. I can live with you. It’s all right to wake up in an indeterminable darkness, not knowing what day of the week it is, and no longer needing to call up the thought of the project I’m working on or dwell on the inexorable nature of modern work. I stay in bed till Amina bangs on the door. The bell’s stopped working.

____________________________________________________________________