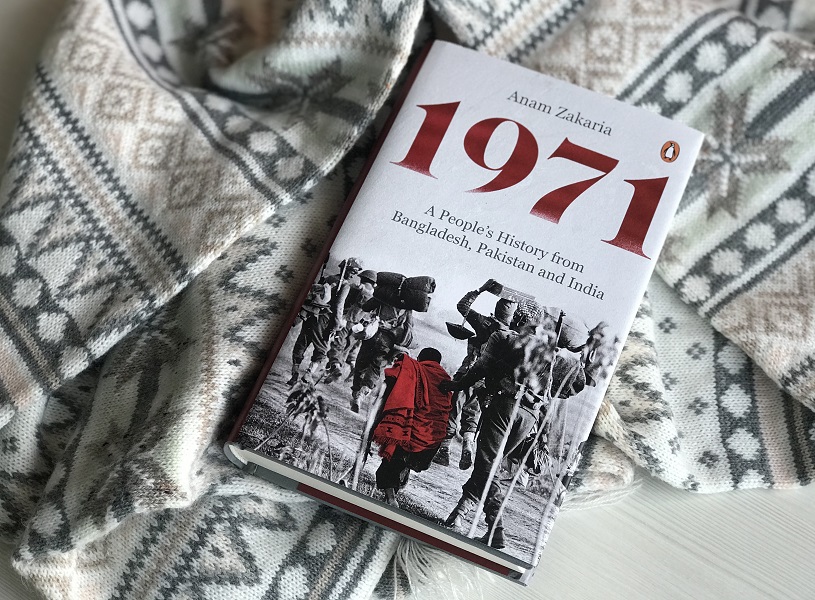

The year 1971 is etched into the minds of the billions that call the subcontinent their home. Post partition, the third Indo-Pak war cleaved through the land to make way for another nation to come into its own. For East Pakistani’s, it was a battle that led to liberation and the birth of Bangladesh. For Pakistan, it was the dismemberment that left behind a sense of loss. For India, 1971 was the war that established it as a nation of humanitarian sensibility and military power.

But what does 1971 mean for the victims and survivors of the war?

Anam Zakaria writes, ‘The war is not just a historical event or a story of gallantry or loss, the war is personal and intimate, the trauma as haunting even forty-eight years later.’ Turning the spotlight away from the state orchestrated narratives of victory and defeat, In 1971: A People’s History from Bangladesh, Pakistan and India, Zakaria draws attention to the festering wounds that victims of the bloodbath bear even today, giving those tormented by terrible memories of heartrending violence a space to voice their experiences.

Read on for a glimpse-

Three men, an officer and two sepoys barged in from the back door, pushing our maid to the side, demanding: “Professor Sahib kahan hai? (Where is the professor)?” When my mother asked why, the officer said, “Unko le jayega (We have come to take him).” My mother asked, “Kahan le jayega (Where will you take him?).” He repeated, “Bus le jayega (We will take him).”’

It was the night of 25 March, when Meghna, then only fifteen years old, had been woken up by her father, a provost at Jagannath Hall, a non-Muslim residence hall at Dhaka University. It was the night Operation Searchlight was launched, the Pakistan Army’s action to crush the secessionist movement in East Pakistan. Dhaka University, whose students were actively engaged in the resistance movement against Pakistan, would be one of the primary targets. The operation would unfold into a long, bloody war, first between East and West Pakistan and then between India and Pakistan, finally culminating in Pakistan’s surrender on 16 December 1971, and the birth of Bangladesh.

‘There was a lot of firing that night, but we assumed that it was the Dhaka University students, excited and eager to show their spirit to Zulfikar Ali Bhutto, who was in town. By then, the firing had become a regular occurrence,’ Meghna told me. ‘Our flat was opposite Jagannath Hall, overlooking the Shahid Minar, the monument for the martyrs of the language movement of 1952. In fact, we were at the centre of all the things that were going on,’ she said, referring to how Dhaka University was one of the major centres of political activity, right from when the language movement started to the 1970s. ‘We even went to see Bangabandhu’s speech of 7 March (held at Ramna Race Course, now called Suhrawardy Udyan) and I remember, my father kept saying, “I don’t see any mediation. I don’t know what will happen.” He feared that the army would clamp down because there was no way they would let things continue as they were . . . The radios were broadcasting their own programmes in Bangla, there were marches happening, there was an active civil disobedience movement. But even then, my father thought the army clampdown would just involve forcing students to stop protesting and return to university, or at most translate into the arrest of teachers (who, the state thought, were instigating trouble). We could never have imagined what happened.’

On 7 March 1971, at the speech that Meghna attended with her father, Sheikh Mujib addressed lakhs of people. By now, Yahya Khan had postponed the opening session of the new parliament. As a result, ‘widespread violence erupted in East Pakistan . . . Mujib was under intense pressure from two sides. Leftist politicians and activists in East Pakistan demanded that he declare independence right away, while Pakistan’s military leaders flew in troops to make sure he would abstain from such a pronouncement.’ Against this backdrop, on 7 March, Sheikh Mujib delivered a historic speech, trying to steer a ‘strategic middle ground’ by emphasizing that until the regime met his conditions, all offices, courts and schools would be closed, and there would no cooperation with the government. Before ending the speech, he also declared, ‘This struggle is for emancipation! This struggle is for independence.’

In her third book 1971, winner of the 2017 KLF German Peace Prize Anam Zakaria takes a closer look at the conflicting narratives on the war of 1971 through the oral histories of various Bangladeshis, Pakistanis and Indians.