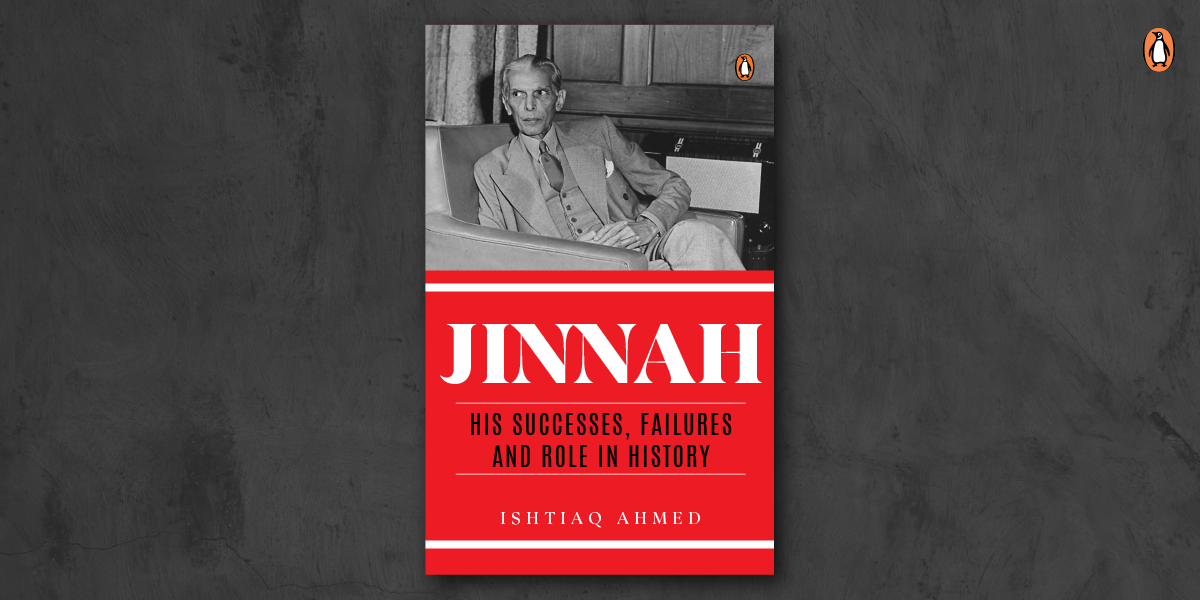

Jinnah

Ishtiaq Ahmed

Mohammad Ali Jinnah has been both celebrated and reviled for his role in the Partition of India, and the controversies surrounding his actions have only increased in the seven decades and more since his death. Ishtiaq Ahmed places Jinnah’s actions under intense scrutiny to ascertain the Quaid-i-Azam’s successes and failures and the meaning and significance of his legacy. Using a wealth of contemporary records and archival material, Dr Ahmed traces Jinnah’s journey from Indian nationalist to Muslim communitarian, and from a Muslim nationalist to, finally, Pakistan’s all-powerful head of state.

Here’s an excerpt from this thoroughly researched and deeply perceptive book.

**

The establishment of Pakistan in mid-August 1947 is proverbially attributed to the sterling leadership of Mohammad Ali Jinnah. The British writer Beverley Nichols, who met Jinnah in 1943, described him as ‘the most important man in Asia’. The chapter on Jinnah was titled ‘Dialogue with a Giant’. The Pakistan government’s officially appointed biographer for Jinnah, Hector Bolitho, noted in his introductory chapter that ‘Pakistan and India were irrevocably divided, largely through Mohammad Ali Jinnah’s imagination and persistence . . .’ Jinnah’s other famous biographer, Stanley Wolpert, paid him the ultimate tribute in the following words: ‘Few individuals significantly alter the course of history. Fewer still modify the map of the world. Hardly anyone can be credited with creating a nation-state. Mohammad Ali Jinnah did all three.’3 In the Pakistani national narrative, homage paid to him is understandably hagiographical. Founders of religion and founders of a state always enjoy sui generis status among their devotees. One can therefore quote many other lavish remarks extolling Jinnah’s extraordinary achievements, but he has his detractors as well who accuse him of being the villain of the piece who bears most responsibility for the bloody partition of India, which claimed more than a million Hindu, Muslim and Sikh lives.

Jinnah had to surmount stiff opposition from the Indian National Congress (hereafter referred to also as the Congress Party, the Congress or the INC), which was then the biggest political party in India, a grass-roots mass organization since the 1920s, with branches all over undivided India and long years of political organization and activity. It demanded freedom from British rule in the name of all Indians in a united India. In opposition to it, the All-India Muslim League (hereafter referred to also as the Muslim League, the League or the AIML) demanded separate states for the Muslims in the north-western and north-eastern zones of India, where they constituted a majority, on the grounds that they were a distinct and separate nation and not merely a large minority (one-fourth of the total population of India). It was an elitist party till 1940, which thereafter rapidly acquired popular support and became a mass party by the time the future of India was put to vote in 1945–46.

Although Jinnah won the case for Pakistan, the partition of India and the two Muslim-majority provinces of Bengal and the Punjab resulted in unprecedented violence and rioting, in which more than a million Hindus, Muslims and Sikhs died, and the biggest migration in history, mostly to escape death and injury, took place; some 12–15 million crossed the international border drawn between India and Pakistan.

**