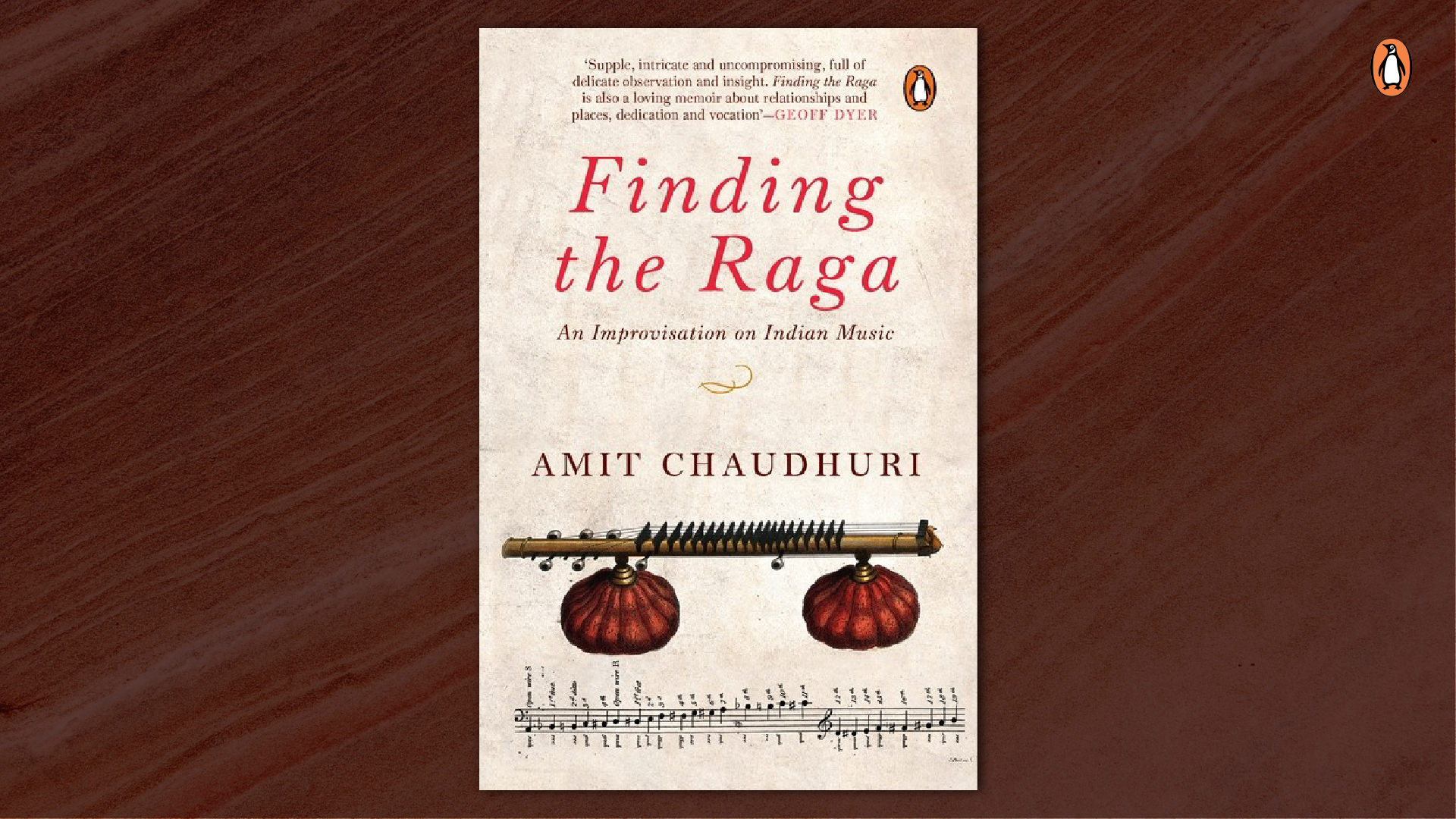

Finding the Raga is Amit Chaudhuri’s singular account of his discovery of, and enduring passion for, North Indian music. A work that simultaneously serves as an essay, memoir and cultural study on an ancient, evolving tradition. It aims at altering the reader’s notion of what music might – and can – be. Tracing music’s development, Finding the Raga dwells on its most distinctive and mysterious characteristics: its extraordinary approach to time, language and silence; its embrace of confoundment, and its ethos of evocation over representation. The result is a strange gift of a book, for musicians and music lovers, and for any creative mind in search of diverse and transforming inspiration.

Here is a glimpse into this profound work of art.

~

Not long ago, I found myself discussing narrative with a group of academics over dinner. Someone said that narrative doesn’t have to have a beginning, middle, and end in that order. I pointed out that there were narratives in which the beginning took up so much time that you didn’t know when you were going to arrive at the actual story. Personally, that was the sort of narrative I liked. I told the academics what the filmmaker Gurvinder Singh had said in a talk in Delhi about the screening of his first film Anhe Ghore da Daan (‘Alms for a Blind Horse’) at a film festival in Canada. Singh said that the ten-tofifteen-

minute prologue – which he showed us before his talk – had presented the director of the film festival with a problem. She wanted him to cut it and move straight to the main narrative. He said he’d rather not show the film at all than dispense with the opening. The film’s prologue was significant. Nothing happened in it except the establishment of a certain meandering lifelikeness. Since this lifelikeness, this quality of constantly revisiting the present moment, is more important to me than the story, I actually wanted Gurvinder’s entire film to have been a prologue.

While writing these pages, I wondered if I could call the first chapter ‘alaap’, thereby playing on the meaning of the main segment of khayal. ‘Alaap’ means – presumably in all North Indian languages – ‘introduction’. It’s also a major component of khayal. The initial delineation of the raga, before the vilambit or slow composition starts to the tabla’s accompaniment, is called ‘alaap’. So is the broaching and exploration of the raga in the vilambit composition, where the singer ascends reluctantly from the lower to the upper tonic, subjecting the notes and the identifying phrases to repeated reinterpretation. This is the alaap too; through a progression of glissandos, it contributes to a full emotional and intellectual engagement with a raga, and can take up to half an hour or more, depending on the singer’s inventiveness or obduracy. The alaap is all; its detail justifies the genre’s name – ‘khayal’, Arabic for ‘imagination’. From alaap we move to drut, fast-tempo segments, which are more virtuosic, less lyrical and tardy in character. No other music tradition allows the prologue to be definitive in this way; not even the Carnatic or South Indian tradition, or the dhrupad, precursor to the khayal, has a counterpart to the alaap’s divagation. Carnatic performance has alapana, a long opening without percussion in which the raga is established. But alapana, like the nom tom alaap in dhrupad, soon takes on a quasi-rhythmic form: that is, the syllables are sung in and out of metre, although percussive accompaniment is still to come in. The rhythmic element in alapana and in the dhrupad’s long introductory passages creates a sort of excitement to do with the climactic; in the khayal, though, all expectation of the climactic is set aside. In fact, the rhythmless alaap in khayal is relatively short; the percussion instrument, the tabla, soon joins the singer, playing a tala (a cyclical measure with a fixed number and allocation of beats) at an incredibly retarded tempo. The singer proceeds in free time, heedless of the tala and the tabla player except when they must return, after an interval, with the composition to the one, the first beat, of the time cycle: the sama. Otherwise, unlike Carnatic music or the dhrupad, free time reigns over the exposition, notwithstanding the tabla, which, in a feat of dual awareness, the singer nods to and largely ignores. The alaap is a formal and conceptual innovation of the same family as the circadian novel, in which everything happens, in an amplification of time, before anything’s begun to happen. At what point North Indian classical singing allowed itself the liberty of making the introduction – that is, the circumventory exploration that defers, then replaces, the ‘main story’ – become its definitive movement, I don’t know; it could go back to the early twentieth century, when Ustad Abdul Wahid Khan’s romantic-modernist proclivities left a deep impress on North Indian performance.

The alaap corresponds with my need for narrative not to be a story, but a series of opening paragraphs, where life hasn’t already ‘happened’, ready for recounting, but is about to happen, or is happening, and, as a result, can’t be domesticated into a perfect retelling. Should I call this chapter ‘alaap’, then? Or should I give the book that name?