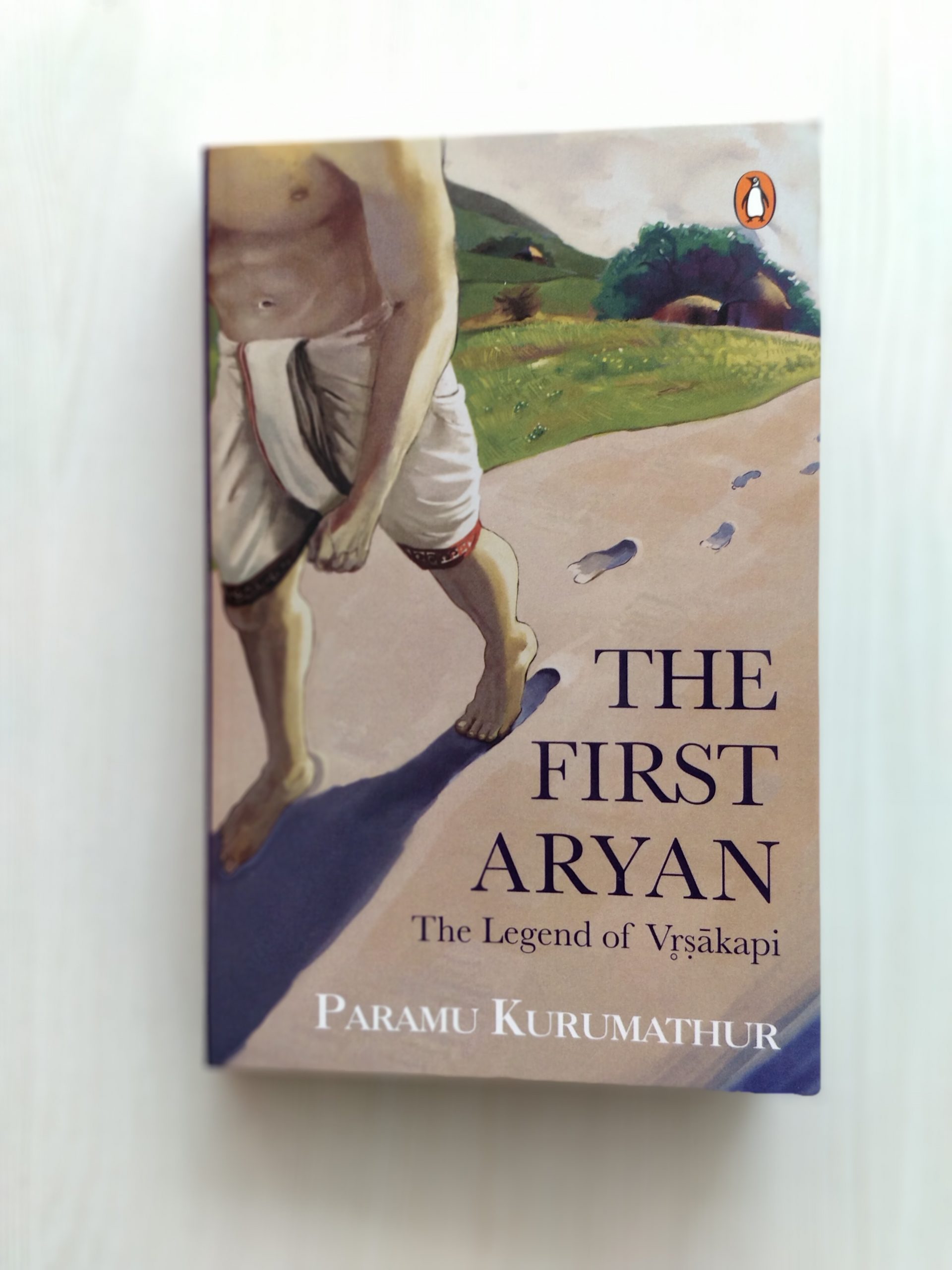

A series of murders have taken place in Parsupur, the capital city of Parsuvarta. Kasyapa and Agastya, two students training to become priests, are asked by their guru to investigate the deaths.

It is an age when Vedic gods are worshiped, religious sacrifices are performed regularly, commerce flourishes and kings are guided by their loyal head priests. But beneath this façade of order lie prejudices and political rivalries, jealousy and power games. This is why the murders, which at first seem to be unconnected, soon lead in the same direction. It is now up to Kasyapa and Agastya to find out the common thread and identify the killer.

Read an excerpt from The First Aryan below:

—

Kaśyapa’s involvement in the intrigues of the royal family and the priestly circles started that morning. Though he had not wanted it, he was dragged into the middle of a series of extraordinary events that were about to unravel in the kingdom of Parśuvarta.

It all started in the capital city, Parśupur, which was located on the gentle inward curve of the Sarasvatī. There were walls, one hasta thick, on the other three sides of the city. Its area was approximately one eighty-first of a square yojana. The city had three gates—one in the south, about one-third the wall’s distance from the river; another in the north wall, halfway into the west–south-west angled section; and the third in the west wall, halfway into the south–southeast section of the wall.

Eleven of Vasiṣṭha’s twelve students were there, in the study hall outside his house. The younger ones were poring over the alphabet and mathematical tables. Kaśyapa and three of his fellow students were working on astronomical and logic treatises. They would first recite the appropriate verses, as they had been taught by their guru, discuss the meaning and implications among themselves and ask their guru or a senior student questions in case they had doubts. Two older students were working on the theory of sacrifices and the esoteric sciences. It was early morning and Kaśyapa was feeling sleepy. However, he toiled on.

Suddenly, he heard somebody mention a senior student, Atharvan’s, name and looked around to notice that he was missing. He asked aloud, to no one in particular, ‘Where is Atharvan? He should have been here by now.’

‘Maybe the guru sent him somewhere on an errand? Maybe he is back at his house? Was he unwell?’

The study hall was in a thatched shed next to their guru’s house. This was no ordinary shed. It was from here that their guru, Vasiṣṭha, had given the kingdom some of its most accomplished priests and scholars. He trained them rigorously—they had to undergo twelve years of basic education, and then a few more of specialized education if they displayed special talent for any of the subjects.

Kaśyapa shivered slightly. It was winter and the woollen shawl he had around him was not warm enough. A feeble sun was just starting to peep through the trees around Vasiṣṭha’s house. There was a cold breeze that entered the shed through the gaps in the wooden planks that made up its walls.

The smell of burning ghee and soma wafted in from the sacrificial field nearby. It was a smell they had grown up with and had got used to. There were other smells in the air too—the smell of the guru’s wife’s cooking and the distant, though distinct, smell of the river in the air. Kaśyapa listened to the cacophony with a smile, as the sound of several students memorizing their lessons seemed to have grown louder. It reminded him of frogs croaking during the rains.

Just then, Bhārgava got into an argument with one of his peers. ‘Well, the gods either respond to our sacrifices or they don’t. We have to decide which.’ The other student was persistent in his scepticism, ‘They certainly do. I have no argument with that. But . . .’

Kaśyapa interjected, ‘Why can’t it be in between? They respond to some sacrifices and don’t respond to others. Logically, there needn’t even be a disjunction between these two propositions. It is not always an either/or situation.

There can be any number of options in between. Let’s not fall into the trap of a false dilemma. We don’t need more reasons for conflict.’

One of the senior students said, ‘Keep quiet. You don’t understand these things. Are you saying that it is always something in between?’

‘No, I am not suggesting a false compromise either. But whatever be the situation, logically, the gods have no choice.They have to give us what we ask for in our sacrifices. Our guru has told us this many times.’

‘Yes. That is what our guru told us. You, on the other hand, are far too young to argue on the matter.’

‘Well, think about it. If you are fed enough, even if you are a god, you will be happy, won’t you?’

Bhārgava was not happy. ‘You are irreverent. I have half a mind to report you to our guru. Now, shut up and do your astronomy.’

Kaśyapa turned to his fellow pupil, Agastya, and said, ‘It is known that the planets go around the earth. It can be proved by the fact that . . .’

They were interrupted by their guru’s wife, Arundhatī, bringing in their morning snacks.

The First Aryan is a one-of-its-kind murder mystery set in the Vedic times.