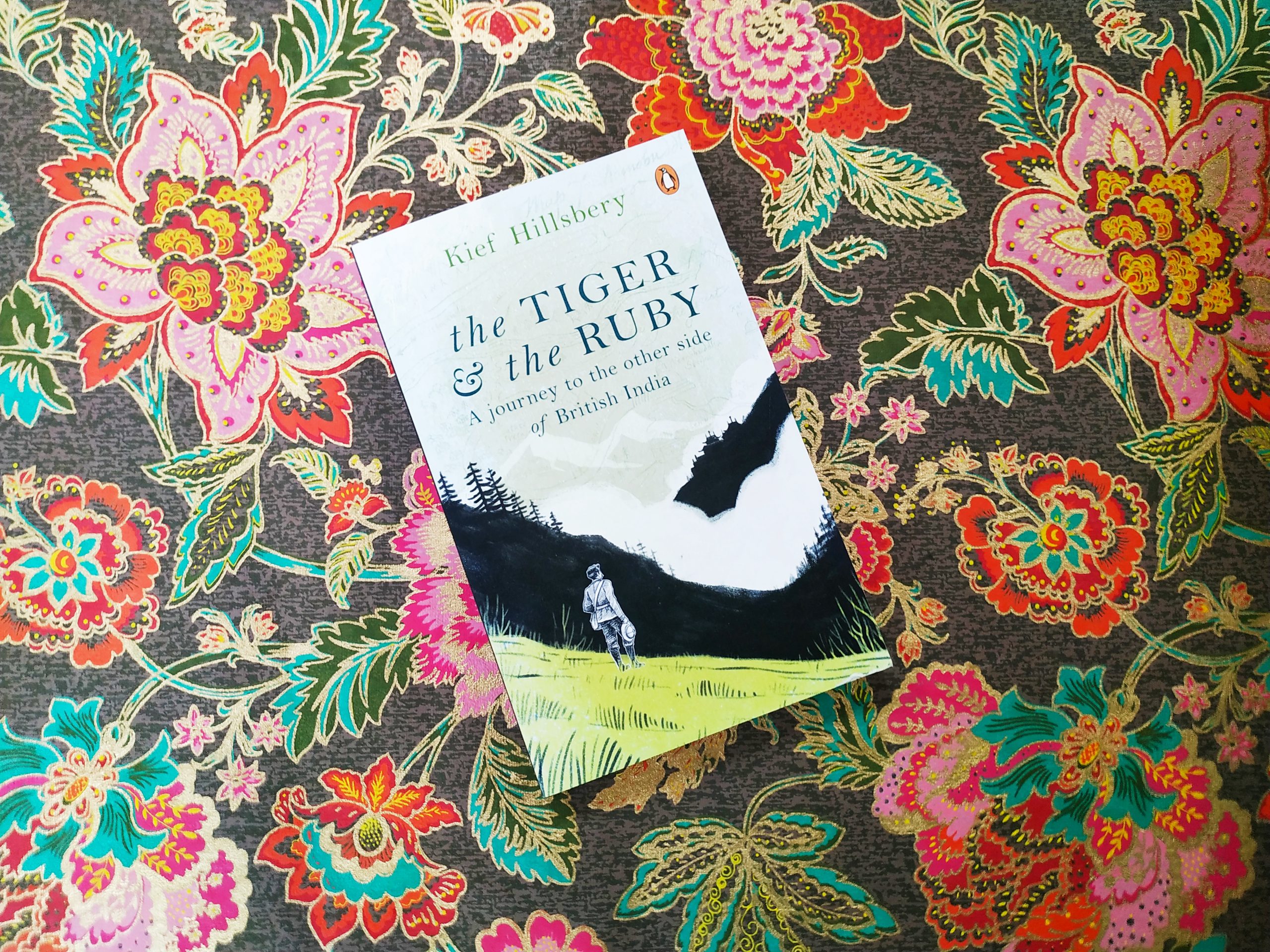

In 1841, Nigel Halleck left Britain as a clerk in the East India Company. He served in the colonial administration for eight years before leaving his post, eventually disappearing in the mountain kingdom of Nepal, never to be heard from again. A century-and-a-half later, Kief Hillsbery, Nigel’s nephew many times removed, sets out to unravel the mystery. Tracing his ancestor’s journey across the subcontinent, his quest takes him from Lahore to Calcutta, and finally to the palaces of Kathmandu. What emerges is an unexpected personal chapter in the history of the British Empire in India.

Here’s an excerpt from the prologue of The Tiger and the Ruby!

Your loving Nigel

“Who was Nigel?” I asked my aunt.

That would be my uncle, she said, many times removed. He had gone out to India.

I asked why.

To help those poor people, she said. “Many men did in those days.” India, she explained, had figured in the lives of several of my ancestors.

A consulship in Burma was mentioned, and there had been a couple of vicars, and someone in railway administration — no, not an engineer, of either sort. Driving a train, she informed me, was common, and as for devising a railway’s route — grades and bridges, tunnels, beds for track — a head for such figures never sat on the shoulders of anyone who bled our blood, she was absolutely sure of that.

How long were they in India, I wondered, and what was it they did afterwards, back in England, and after she told me — two or three years for the consul and the clergymen, five she supposed for the railwayman, and more or less the same as what they did in India, practised their professions — I returned to Uncle Nigel: what did he do?

“Do?”

“In England. After India.”

Actually, she said, he never came back. He stayed in the East.

“His whole life?”

“Indeed he did.”

“He must have liked it.”

“I suppose he must.”

“Was he the only one ever? Who stayed?”

“Heavens, no. Many have. Why, Mother Teresa —”

“In our family.”

No others came to mind, she said. Not for India. There was my mother, of course, who married my American father after the war and decamped across the pond.

“Did Nigel get married? Was that why? To an Indian?”

“Certainly not. Of course not.”

“He never had a wife?”

“I’m afraid not.”

The brooch had been a gift to his mother, she said. Then she changed the subject, leaving me with both a clear sense

that she disapproved of Nigel and the vague notion that there was more to his story than my aunt thought suitable for sharing with my ten-year-old self. A decade later, when I was on the verge of heading East myself for a college year abroad in Nepal, my mother confirmed my suspicions.

Nigel, she confided, had separated from the East India Company under some sort of cloud. Afterwards he had supposedly “gone native” in Nepal and lived until his death in 1878 as one of a handful of Europeans admitted to the then-forbidden Himalayan kingdom.

According to family legend, his exile was forced — he couldn’t stay in India or come back to England. But no one quite knew why. He might have been a jewel thief, he might have been a spy. He was, everyone agreed, a hunter of big game, and one story had it that he met his end in the mouth of a man-eating tiger in the Terai jungle, on the border of Nepal and India.

Get your copy today!