In the idyllic village of the Abode of Contentment, Durga and her little brother, Opu, grow up in a world of woods, orchards and adventure. Nurtured on their aunt’s songs and stories, they dream of secret magical lands, forbidden gardens and the distant railroad. The grown-up world of debts, resentment and bone-deep poverty barely touches them.

A powerful testament to the indomitable human will to prevail, Pather Panchali is a timeless novel that comes alive in an incandescent new translation.

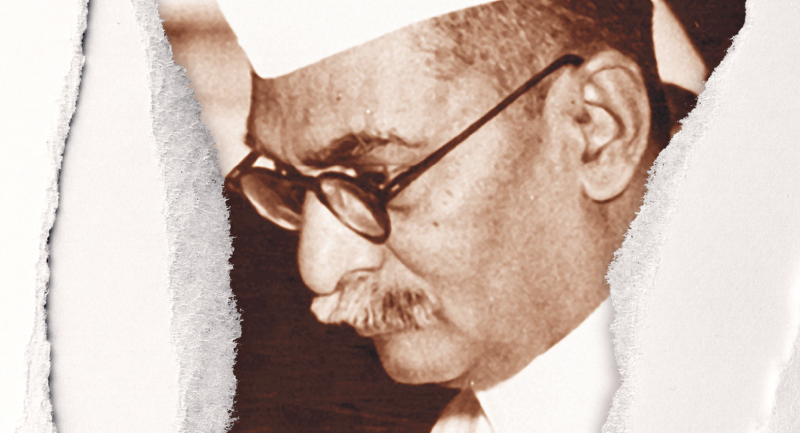

This book brought world-wide recognition to Bengali writer Bibhutibhushan Bandopadhyay.

A film on the novel was also by well known filmmaker Satyajit Ray.

Read an excerpt from the book below:

—

Horihor Roy’s tiny ancestral home marked the easternmost border of the Abode of Contentment. A few acres of inherited land and annual tokens of respect sent by his disciples were his only income, and cracks were beginning to show in the family’s budget.

Indir Thakrun was demolishing a bowl of puffed rice in the veranda. The previous day had been Aekadoshi, and the mandatory fasting had left the elderly widow ravenous. Horihor’s little girl, Durga, sat close by, her wistful eyes watching as each fistful travelled from the old metal bowl to her paternal aunt’s mouth—a hopeless chasm of no return. Once or twice it seemed like she was about to say something, but each time, she swallowed her words at the last minute.

When the bowl was finally empty, Indir Thakrun looked up and immediately saw the longing in her niece’s eyes. ‘Will you look at me!’ she exclaimed. ‘A whole bowl of puffed rice, and I didn’t even save a little bit for my little girl!’

Though this had clearly been Durga’s own unvoiced tragedy, she managed to put on a brave face. ‘Is okay, Piti.You hungwy today. You eat.’ But her bright young eyes lingered longingly on her aunt’s empty bowl.

Indir Thakrun looked swiftly around. The usual watching eyes were absent, if only for the moment. Satisfied, she grinned conspiratorially at her niece and quickly broke one of her two ripe bananas in half. Then she held one half out to the child. The strained nonchalance of Durga’s face dissolved instantly into an enormous grin of pure delight. Taking the treat eagerly from her aunt’s hand, she jammed one end in her mouth, and began sucking it like one would a hard-boiled sweet. Her eyelids fluttered shut in contentment.

At that very moment, a sharp voice rang out from within the cottage: ‘Dugga! Have you sneaked off to your aunt’s again?’

The child’s eyes snapped open. Unable to answer through a mouthful of the forbidden treat, she glanced beseechingly at her aunt.

‘She’s not doing anything, younger sister-in-law,’ Indir Thakrun supplied hurriedly, trying to divert the child’s mother’s temper. ‘She’s just sitting here with me.’

‘She has no business “just sitting there” when you’re eating!’ snapped the invisible voice. ‘Greedy, disobedient child! How many times do I have to tell you not to hang about people when they are eating? Come inside at once!’

There was no counter to such a direct order. Casting a last, longing look at the sunny veranda and her helpless aunt, Durga slowly followed the direction of her mother’s voice.

~

Though fed on his sparse coin, Indir Thakrun was only distantly related to Horihor—a cousin of sorts on his mother’s side. But her kinship to the village was far older than his. Her family, the Chokrobortis, could trace their roots back to several generations in Contentment. On the other hand, Horihor was the son of an immigrant, only a first-generation resident. Indeed, had it not been for Horihor’s father’s keen desire to acquire a second wife, the Roys might not have set foot in Contentment at all.

The story of their arrival went like this: Ramchand Roy, then the eldest living son of the Joshra-Bishnupur Roys, had lost his first wife while he was still quite young. A man becomes easily accustomed to the comforts of conjugal life, and Ramchand felt the pangs of widowerhood rather keenly. His father, he noted gloomily, wasn’t making any effort to secure his bereaved heir a much-needed second wife. Naturally, as a decent young man, he couldn’t bring up the matter of his own second wedding; however, when waiting hopefully in silence for several months failed to fetch him a bride, he decided to begin hinting at the travails of his singlehood.

During hot afternoons, when the household had retired gratefully for naps into dark, cool rooms, Ramchand would begin to roll about in his bed, moaning and groaning loudly enough for the whole household to hear. When alarmed relatives rushed in to ask what was wrong, Ramchand would pretend to wilt in agony. ‘Does it matter?’ he would ask, forlornly. ‘It is my lot to suffer in solitude for the rest of my life! There’s no one to tend to me when I have a headache, no one to care for me when I have an upset stomach. Indeed, if I were to die tomorrow, there is no one in this house to even care! Oh, this loneliness—I can’t bear it!’ Then he would roll about on his bed some more, and groan pathetically.

It’s hard to say, after all these years, whether Ramchand’s father was finally worn down by the constant assault on his afternoon naps, or whether he had intended all along to wait a while before finding his son a second wife. But shortly into Ramchand’s campaign for a companion, his second marriage was arranged to the only daughter of Brojo Chokroborti—a rich farmer from the neighbouring village of Contentment.And that was how the Joshra-Bishnupur Roys first established their connection to this village.

Ramchand’s father passed away soon after the wedding, and Ramchand—still quite young—moved his family to Contentment to be under the guardianship of his father-in-law. However, he took care to pick a different neighbourhood than his in-laws, lest people talked.

People eventually did talk, for Ramchand’s wife and children were obliged to spend nine months out of twelve under his father-in-law’s roof. It wasn’t that Ramchand was a dissolute or a wastrel; in fact, under his father-in-law’s care, he attended the local Sanskrit school in Contentment and eventually became a fairly well-respected scholar. But he was plagued by an incurable lassitude. All disciplines of profitable engagement bored and exhausted him. He much preferred to spend his days in conversation and games of dice, excusing himself from the community courtyard only briefly to eat lunch and dinner in his in-laws’ kitchen.

Occasionally, his friends and neighbours felt compelled to remind him that even the most accommodating of fathers-in-law could only contrive to be alive for so long. If Ramchand failed to settle into a career while Brojo Chokroborti was still around to help, how would he support his wife and child when the old man passed away?

Pather Panchali is available now!