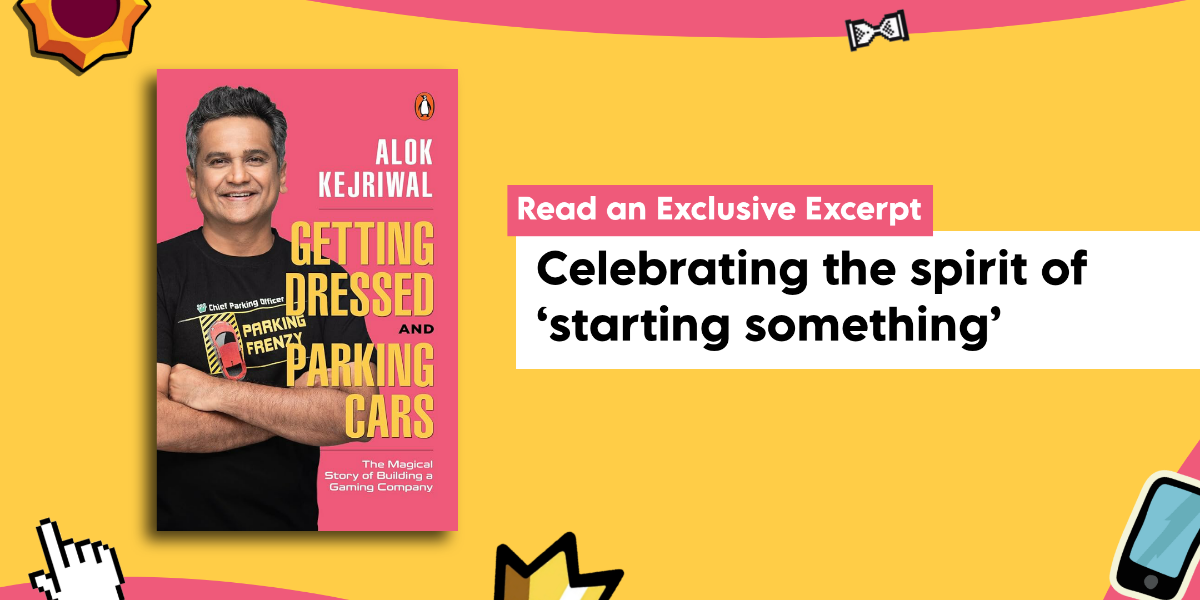

Join the exciting ride with Alok Kejriwal in Getting Dressed and Parking Cars. The book takes us into the world of Games2win, a startup that dreams big in the gaming world. Imagine creating a game inspired by the crazy streets of Mumbai and the Iconic Kaali-Peeli Bombay taxi– it’s all part of the fun!

Read this exclusive excerpt for a quick ride in the taxi that’s set to win the race.

Put your seatbelts on!

***

I quietly assembled a small team from my previous companies to fire up the Games2win engines and was happy to see how excited they all were. My team and I had been involved in client service for years, and we were yearning to get started on building our own products.

I again turned to my colleague Dinesh Gopalakrishnan and decided he would be responsible for the car games vertical. My instructions to him were clear—‘Dinu, you need to start making brand new parking and driving games. They need to be casual, differentiated and fun. Also, I need at least ten unique titles split equally between the two types. So, step on the pedal and hit the road now (pun intended)!’ Dinesh was excited and went all in.

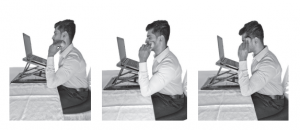

Before mandating Dinesh to make casual car games, I had thought very hard about the genre. How could I make driving and parking games ‘easy to play, but impossible to master’ (the magical recipe for creating great games)? What would make these games sticky and addictive despite being casual and snacky (meant to be played for short periods)?

My insight came quickly.

Real-life driving was the best reference!

In the real world, we drive or travel in a car from Point A to Point B without colliding with vehicles, objects or pedestrians. It’s impossible to imagine driving in the real world while having mini accidents on the way.

Leveraging this insight, I decided to build online car games with the opposite scenario. I wanted our online car games to be designed such that it would be impossible for a first-time player to navigate the car without an accident.

In the online game, while navigating congested roads and avoiding collisions with other vehicles, obstacles, pedestrians etc., players would not be able to complete a mission on the first attempt. After trying and losing the first time, the player would wish they had been more careful and would take another stab at playing the level.

Having bettered themselves, even if the player succeeded in winning the first level, the next level would be designed to ensure that a steep learning curve would be required to pass that level (play multiple times). The rest of the levels would gradually get harder and harder.

I was implementing the golden ‘easy to play, impossible to master’ game-level design mantra to make my first set of games.

Using this principle, a simple, well-designed game with minimum content could deliver multiple gameplays while providing endless entertainment to the player.

After understanding my design concept, Dinesh took up the task seriously and started game creation.

When we began thinking creatively for these car games, one exciting idea we devised together was a game called ‘Bombay Taxi’. The idea’s genesis was the streets of Mumbai. The ubiquitous black and yellow or kaali-peeli taxis, as they are fondly called, were unmissable and distinctly Mumbai.

If you haven’t sat in a Mumbai taxi, you should bump it up to the top of your list of must-dos. The varied interiors, stickers, idols of gods of all religions perched in the centre of the dashboard, and the beads, malas and flowers dangling from every available hook in the front section will awe you. And at night, the interior lights and illuminations on offer can give the world’s best designers a run for their money! Unsurprisingly, the first ever Apple store in India, which opened in 2023, is located in Mumbai and has drawn strong design inspiration from the inimitable kaalipeeli taxis!

Driving in Mumbai is hard. It means being super adept at navigating choking traffic, narrow roads, marriage, funeral and religious processions, avoiding crater-sized potholes, driving through flooded streets, zip-zapping two and three-wheelers and obeying all traffic rules and signals.

I often tell people, ‘If you can drive a car in Mumbai, you can drive a car anywhere in the world!’

The reality of Mumbai driving became our game design, and Dinesh created different types of Bombay taxis (typically, older generation Fiat cars, small SUVs and mini cars) with distinctive stylizations. He designed terrific ‘street levels’ in Mumbai that featured fisherwomen selling their wares on the road, confusing railway crossings, kids playing cricket on the main streets, hawkers selling their

wares almost everywhere, cows doing their own thing, food sellers, handcart pullers and the notorious ‘three-wheeler’ drivers, all contributing to the confusion and chaos that embodies the Maximum City .

Dinesh also amazingly recreated the sounds of Mumbai roads, featuring a cacophony of cars honking, hawkers shouting, trains, buses and trucks blowing their horns, street music and other typical Mumbai sounds.

The final car-driving game he produced was fantastic. The moment I started playing it, I couldn’t stop. When I finally did, about forty minutes had passed!

No sooner did the game go live on games2win.com than it became a super hit! It was bound to be.

***

Get your copy of Getting Dressed and Parking Cars by Alok Kejriwal wherever books are sold.