How does a Parsi lawyer, deeply influenced by the principles of Roman Catholicism, fall in love with a Bahá’í and go on to become the Attorney General of India for a Hindu nationalist BJP government? How does a boy with a broken leg, who studied in a Gujarati-medium school, and lost his father at the age of nineteen, go on to mount a heroic defense of the Janata government’s decision to dissolve Congress state legislatures (in 1977) in the Supreme Court? How does a lawyer with a humdrum customs and excise law practice, whose grandfather sold horsedrawn carriages in Bombay, become a U.N. human rights rapporteur, and repeatedly defend the fundamental right to free speech and expression in the Supreme Court of India?

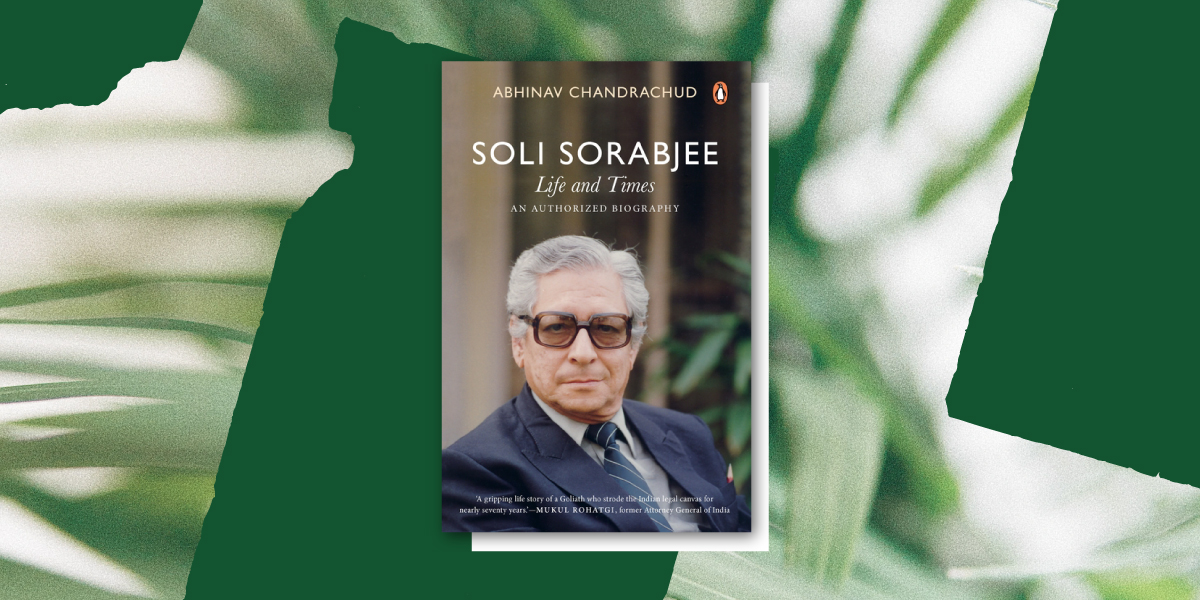

Let’s read an excerpt from Abhinav Chandrachud’s latest book Soli Sorabjee, Life and Times: An Authorized Biography.

*

A lawyer’s first brief is always considered to be very memorable. Sorabjee’s first brief was given to him by a Parsi attorney, Naval Vakil, a partner at Little & Company, a firm which used to heavily brief his senior, Kharshedji Bhabha. It was not a very serious brief. Sorabjee just had to ask Justice S.T. Desai for an adjournment in the case. Vakil sent Sorabjee the brief along with a thoughtful note. It said: ‘I hope it leads to more success.’ However, in this, his very first case at the Bombay High Court, Sorabjee failed. The judge refused Sorabjee his adjournment.

Even so, Sorabjee marked a fee of two ‘gold mohurs’ for his appearance in the case, equivalent to thirty rupees. Since the colonial period, Bombay advocates marked their fees in gold mohurs, where one gold mohur was worth fifteen rupees. Even today, it is common to see fees being marked in gold mohurs or ‘gms’ on the Original Side of the Bombay High Court.

Sorabjee’s practice started slowly. Between 1953 and 1955, in the first ten important cases that he appeared in (i.e., cases that were either reported in the law reports or written about in the Times of India), Sorabjee was led by a senior and did not offer any independent arguments in court. Naturally, the senior advocate he was ‘led by’ most often in his cases in the early days was his own senior, Kharshedji. By 1957, however, around 4 years into his practice, Sorabjee started arguing cases on his own in the Bombay High Court. Between 1953 and 1970, before Sorabjee became a senior, he argued 63 per cent of the important cases that he appeared in himself. In other words, even as a junior, the majority of the briefs that Sorabjee received were those in which he had to stand up in a packed courtroom, face the judge, make his arguments, and try to obtain a favourable outcome for his client. This number rose substantially after he became a senior advocate. Between 1971 and 1975, after Sorabjee became a senior and up to the eve of Indira Gandhi’s Emergency, Sorabjee argued 81 per cent of the important cases that he appeared in himself. Like Kharshedji, Sorabjee appeared mostly on the Original Side of the Bombay High Court. Like him, Sorabjee appeared both before a single judge and division bench in equal proportions.

There is no doubt that Parsi connections helped Sorabjee. He grew up in a wealthy, well-connected Parsi family. He was privileged. He did not have to worry about earning money in the early days of his law practice, to pay rent or to support a family. He studied in schools that had a high proportion of Parsi pupils. He got into the chamber of a prominent Parsi advocate, Kharshedji, his cousin’s husband. He got his first brief from a Parsi attorney. However, that is as far as Parsi connections could take him. In order to succeed at the Bombay Bar Association, Sorabjee had to perform well as a lawyer, in the absence of which his benefactors would soon have abandoned him. Most of the judges and clients were non-Parsis. Between 1953 and 1975, for instance, in the 132 reported cases in which Sorabjee appeared, only 22 (16 per cent) had a Parsi judge on the bench.

Sorabjee started getting noticed by the judges of the Bombay High Court a few years into his practice. In 1957, Chief Justice M.C. Chagla, a non-Parsi judge, appointed Sorabjee as an ‘amicus curiae’ or ‘friend of the court’ to assist the court in a divorce case under the Hindu Marriage Act, 1955. Chagla must have seen a spark in Sorabjee and tried to encourage him by appointing him as an amicus. Chagla concluded his short judgment in the case with the following line: ‘We are thankful to Mr Sorabjee who assisted this Court as amicus curiae.’ In many cases, Sorabjee did things that might have helped him gain the trust of the court. He cited judgments against himself—informing the court about cases that were decided against the point that he was making. Judges therefore knew that Sorabjee was not the kind of lawyer who would obtain favourable orders by hiding things from them. He made concessions in court, giving up legal points that he felt were not worth arguing. In a case in 1969, for instance, the additional judicial commissioner in Goa noted in his judgment: ‘Shri Sorabjee, appearing for the petitioner, candidly conceded, and I think very appropriately, that the petitioner had not been able to substantiate the allegation of mala fides.’ In important cases, he went to the court prepared to argue a series of well-articulated propositions. All this earned him praise from the bench. In one case in 1965, which he argued against the rising star of the Kharshedji chamber, Fali Nariman, Justice V.D. Tulzapurkar remarked: ‘[B]oth Mr Nariman and Mr Sorabjee submitted arguments with great ability’. Nariman and Sorabjee appeared against each other often, each one getting the better of the other in nearly equal proportions.

Between 1953 and 1975 Sorabjee had a large customs and excise practice (an ‘excise’ tax was a tax on goods produced or manufactured in India—it was replaced by the ‘goods and services tax’ or GST in 2017). About 26 per cent of his work at this time was in that branch of law. However, his other large practice areas included labour cases, company cases, landlord-tenant disputes, tax cases, commercial suits, cases involving evacuee property or land requisition and cases concerning foreigners or passports.

**

Read this first authorized biography of Soli Sorabjee by getting your copy from your nearest bookstore or online.