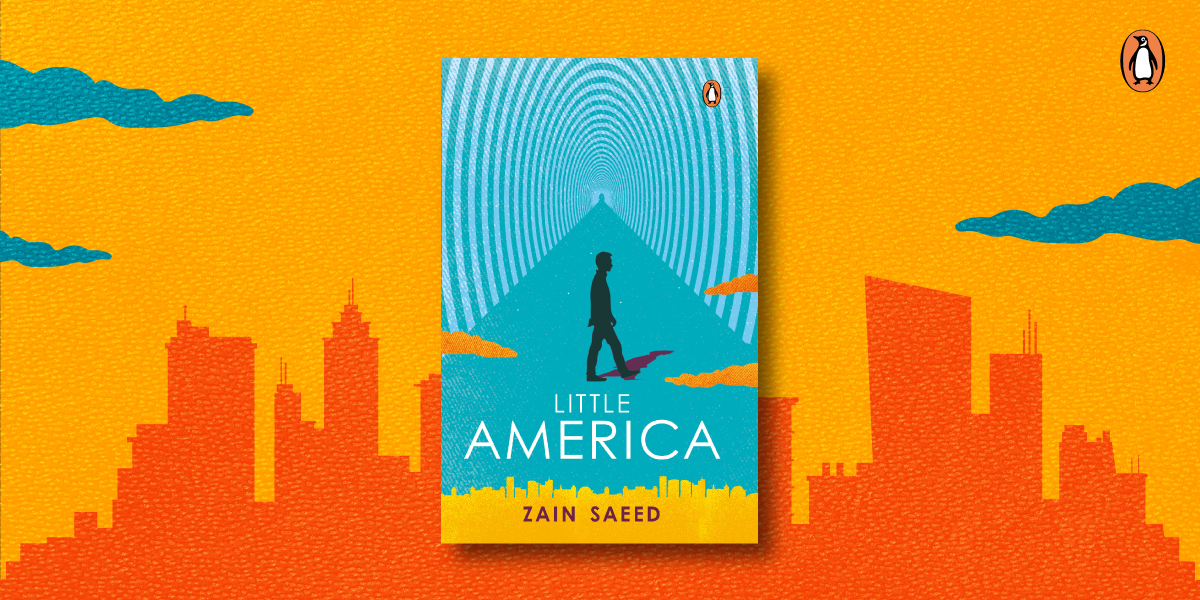

Born in a Karachi slum, Sharif Barkati became obsessed with American ideas of love and freedom at a very young age. He began to dream of a public place in the city that did not follow the rules, where people would be free to say and do whatever they wanted under open skies, away from the conservative eyes of Pakistani society.

With the help of his friend Afzal – and TJ, an extremely wealthy Pakistani-American – Sharif was able to realize his dream in the form of a colossal compound on the Karachi coast, full of bars, cafes, clubs, and the people of Karachi strolling about, hand in hand.

They called it Little America.

Now in prison, Sharif tells the story of his life in a letter to his favourite novelist, hoping that he will turn it into a literary masterpiece. At once a rollicking journey around the mind of a man desperate to be free, an allegory of the neo-colonial endeavour, and an investigation of the desire to emulate the perceived superior while desperately trying to hold on to one’s own cultural identity, Little America asks the question: What, really, is freedom, and what can be sacrificed in its name?

Here’s a taste of the book. Read on to get a glimpse into Sharif’s life while he was a young boy still forming his ideas about such worldly matters.

~

I kept asking Baba what that was, all the touching and the kissing on TV, at the cinema, and he pulled at his moustache, and thrusting out his bony chest—not more than five feet off the ground—told me it was just a thing Americans did, told me they would all go to hell.

I had no friends, you see. No brothers. I stayed at home and memorized my time tables and ABCs and God is Great and spoke to no strangers, because Baba told me I was supposed to become a big man. I missed out on the gossip of the slum boys, and the schoolboys (I went to a school beyond the trash, in the city, God bless Baba), never partook in the stealing of video tapes, comparing sizes of appendages; missed out on it all. I ached with curiosity, but I was a good boy, and I was going to be a big man—and that is what I became!—and I was sure it was all for my own good. I accepted the censorship as a necessary thing.

But like a climber infatuated with the top of a mountain, I was smitten, enthralled by the power those images held over a cinema full of grown-ups. I had no idea what it meant, what it led to. It was simply the coming together of two bodies, so close, so close, closer than I had ever seen in the quotidian, that fascinated me, led me to daydream in English class on a sunny day, wondering what made a

thing wrong, what made it right.

I used to have a baby sister. As I think about it now (forgive the drops of sweat that have smudged these lines) I realize that I do not remember my mother ever sprouting a belly before she gave birth to her. I had no conception of it—I simply could not see it!

On the day in question, Baba told me to leave the house for a few hours, go play with friends I didn’t have. He told me that when I came back, there would be someone in the house who would call me Bhai. I picked up my English books, and did as I was told, skipped out of the house thinking imagine that! Imagine that! Me! A brother!

When I came back at sunset, nothing had changed, except for a splash of blood on the bed sheets. Baba sat hunched in a corner. I remember Amma, like a punctured balloon tied to a bedpost, sprawled

on the mattress. She lay there all day with her eyes closed. I did not ask, and I was not told. Imagine that! God making a dead baby! I thought about it a few years later, after I’d discovered the magic present in the bodies of all women, and I wondered if my parents’ distrust of hospitals had caused the death—oh, how I fumed!—their lack of education, their insistence on having a pregnant woman pray five times a day, their backward, Pakistani ways. I know now, of course, that life is simply like this, everywhere—it just seems different based on where you imagine it from—but when I was still convinced of my parents’ blunders, it shoved me clattering closer to the idea of Little America indeed.

In the weeks and months following the little one’s day of birth, our one-room house got bigger in the mornings and afternoons, because Amma no longer walked around, humming, and Baba went back to the office. Before I forget: he worked at some lawyer’s firm as a typist—he couldn’t read or understand English, just knew what every letter looked like and where to find it on the typewriter. His employers knew as much, had hired him for that exact reason, so that he could type up sensitive handwritten documents and not have a clue what they said. He used to bring home scraps of these typewritten documents, ones on which he’d made mistakes, and ask me what they meant. I could not tell him much more than that they mentioned large sums of money and the names of the people who had it, along with several other sentences that I was simply not cut out to read. I think this might have inspired my desire to read in the following years—I wanted to be able to tell Baba everything, let him know what his employers would not: the importance of his work, his worth, his ability to affect the lives of strong people.

He worked so hard, my friend. Sometimes he did not come home till eight in the evening. On these days, with Amma having taken to the bed, I had time after school unsupervised, so I took to renting out films from Lucky Video. Baba had started giving me money for lunch ever since Amma’s sadness (Rs 10 a day) and I used it to rent out love stories, for I realized early on that that is where most of the kissing would be. With the lack of food in my body, I grew even thinner, but stopped short of disappearing, and

that was enough.

I’d bring the film home. I’d tiptoe around the house, around Amma’s slow breathing form, whispering ‘Amma! Amma!’, a part of me wishing her to wake up, the other part hoping she’d stay asleep so I could watch my movie. I’d sit next to her head on the mattress, not touching, but feeling content in the slight movement of the foam of the broken mattress whenever she moved. Her eyes never opened, and if she noticed me she did not say, continued her mourning curled up on the bed.

On those afternoons, it was just me and the TV and the VCR, and the volume turned way down low.

Oh the things I saw!

Oh the love I felt!

Oh the joy, the joy!

Sadness, too—who enjoys a mother in strife?

But children cope. Do they not, my friend?