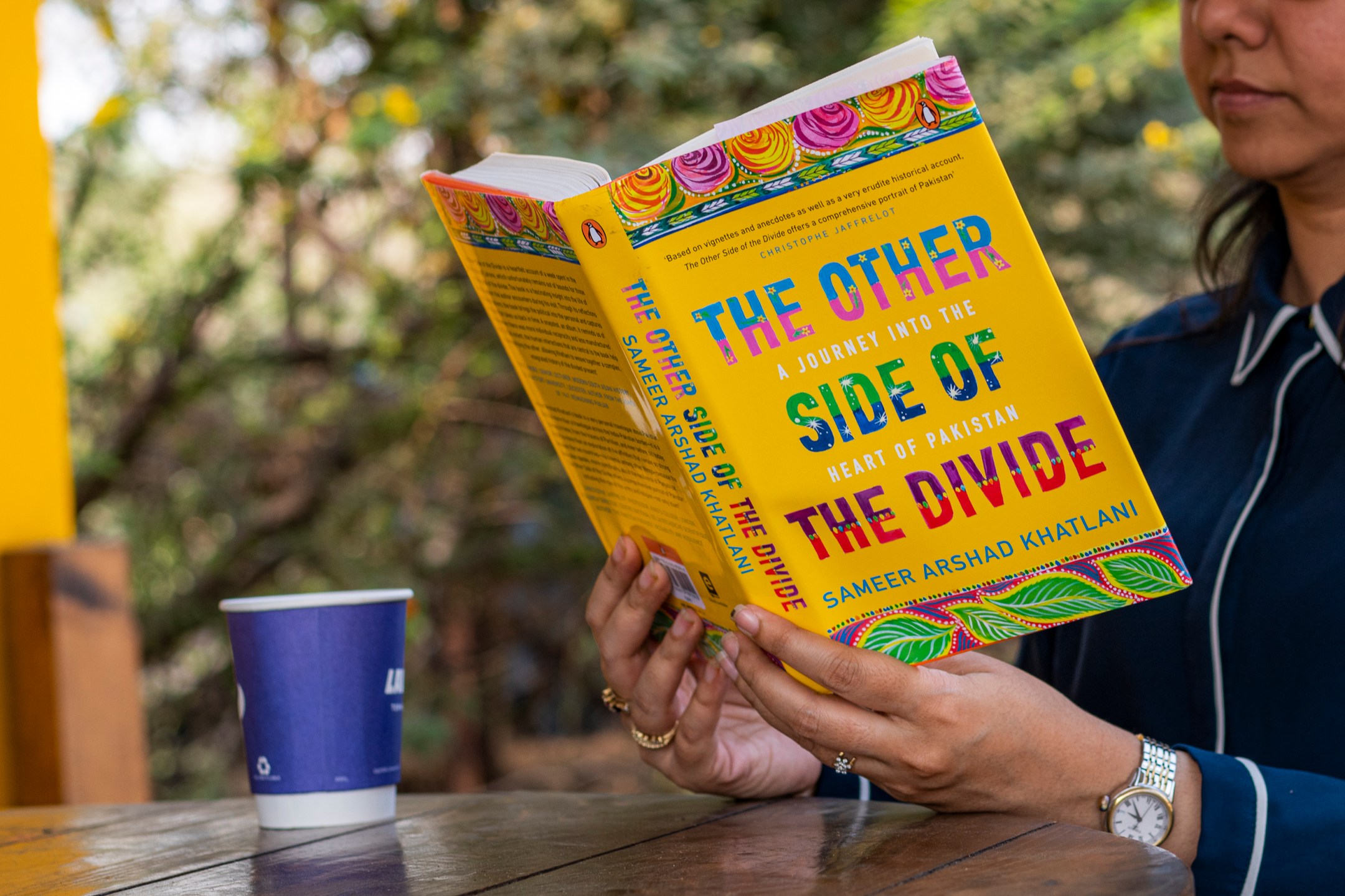

Many of us have concluded Pakistan as an economically, culturally, socially and ideologically regressive country. Most of us have dropped the idea of exploring the picturesque landscape of Pakistan due to a dangerously false perception of it being a terrorism inflicted country. That is why when a journalist – Sameer Arshad Khatlani, decided to attend the World Punjabi Conference in Lahore, his family felt extremely anxious about his decision.

The Other Side of the Divide is a journalist’s reflective travelogue that bares the complexities of culture and class in Pakistan. Khatlani’s adventurous journey to the heart of Pakistan reveals the connecting thread between two nations through stories that fail to reach the masses in India.

Here are some excerpts that render all commonly held stereotypes about Pakistan as false:

Stereotype: Pakistan is a land that breeds hostility

‘The immigration clearances were prompt. I had never seen a more cheerful immigration official than the one who stamped my passport. the atmosphere was not even remotely as hostile as what it used to be a decade ago. […] I did not find any hostility. Far from it…’

Stereotype: Pakistan is full of only Muslims

‘Everything across the border looked as if harmonized with the Indian side. […] An artificial line drawn through the heart of Punjab cannot be deep enough to change the shared language, culture, customs, idioms and attitudes shaped over centuries. Sikh men in their beautiful and colorful turbans in eastern (Indian) Punjab and ubiquitous Urdu in western (Pakistani) Punjab are perhaps the only outliers on the surface. Punjabi is the language of the people on the street.’

Stereotype: Pakistan rejects everything that is Indian

‘The market was abuzz despite the cold. it could have been easily mistaken for a market in Indian Punjab had not it been for Urdu signages. Virtually every shop sold artificial jewellery, Indian beauty products and prominently displayed Amul Macho undergarments packs with pictures of Bollywood stars Saif Ali Khan and Akshay Kumar.’

Stereotype: Cities in Pakistan aren’t as developed as India

‘The Pak Heritage is a budget hotel particularly popular with Sikh pilgrims. it is located on the busy and mostly gridlocked Davis road with many similarities with Delhi’s Daryaganj. […] In Lahore, posh, leafy and well-maintained areas like the Mall are located just a few kilometers away, south of Davis road. Daryaganj, likewise, is a five-minute drive from the heart of tree-shaded Lutyens’s Delhi, distinguished by its colonial-era bungalows and wide avenues.’

Stereotype: Bollywood doesn’t have Pakistani fans

‘… one of Pakistan’s best-known newspapers, Dawn, gushed about Madhuri’s ‘dazzling and disarming smile’, which she ‘quite literally patented’ and honed ‘into an art form’. […] In Lahore, and indeed across Pakistan, Bollywood is ubiquitous and gets prime slots on TV news channels, sometimes at the cost of more pressing issues.’

Stereotype: Pakistan has an extremely orthodox culture

‘No one disappeared after the screening. A party-like atmosphere continued outside the hall well past midnight. Television crews surrounded filmmakers and socialites for sound bites about the film. Camera flashlights brightened the dimly lit waiting area. Some spoke to at least half a dozen camera crews about the film and performances of the lead actors, Aamir Khan and Katrina Kaif.’

Stereotype: Pakistan has an Urdu speaking community

‘Punjabi, along with its variants, still remains the mother tongue of an overwhelming number—close to 60 per cent—of Pakistanis. Beyond the urban upper-class pockets of Lahore and other bigger cities, it remains the colourful language of choice for the masses…Urdu-speakers have accounted for roughly 10 per cent of Pakistan’s population.’

To understand how the common people of Pakistan have often challenged the dehumanizing discourse about their country, there may be no better place to begin than The Other Side of the Divide.