Bright-eyed aspirants in sports-from badminton to gymnastics-are training across the country. Homegrown leagues are attracting the world’s best athletes and professionals. The country boasts multiple World No. 1 teams and athletes, and sporting achievements are handsomely rewarded.

Go! features a never-before-seen collection of essays by leading athletes, sports writers and professionals, who together tell a compelling story of India’s ongoing sporting transformation.

Read an interesting excerpt from the chapter, “Building Indian sports Champions in India”, written by Abhinav Bindra:

——————————-

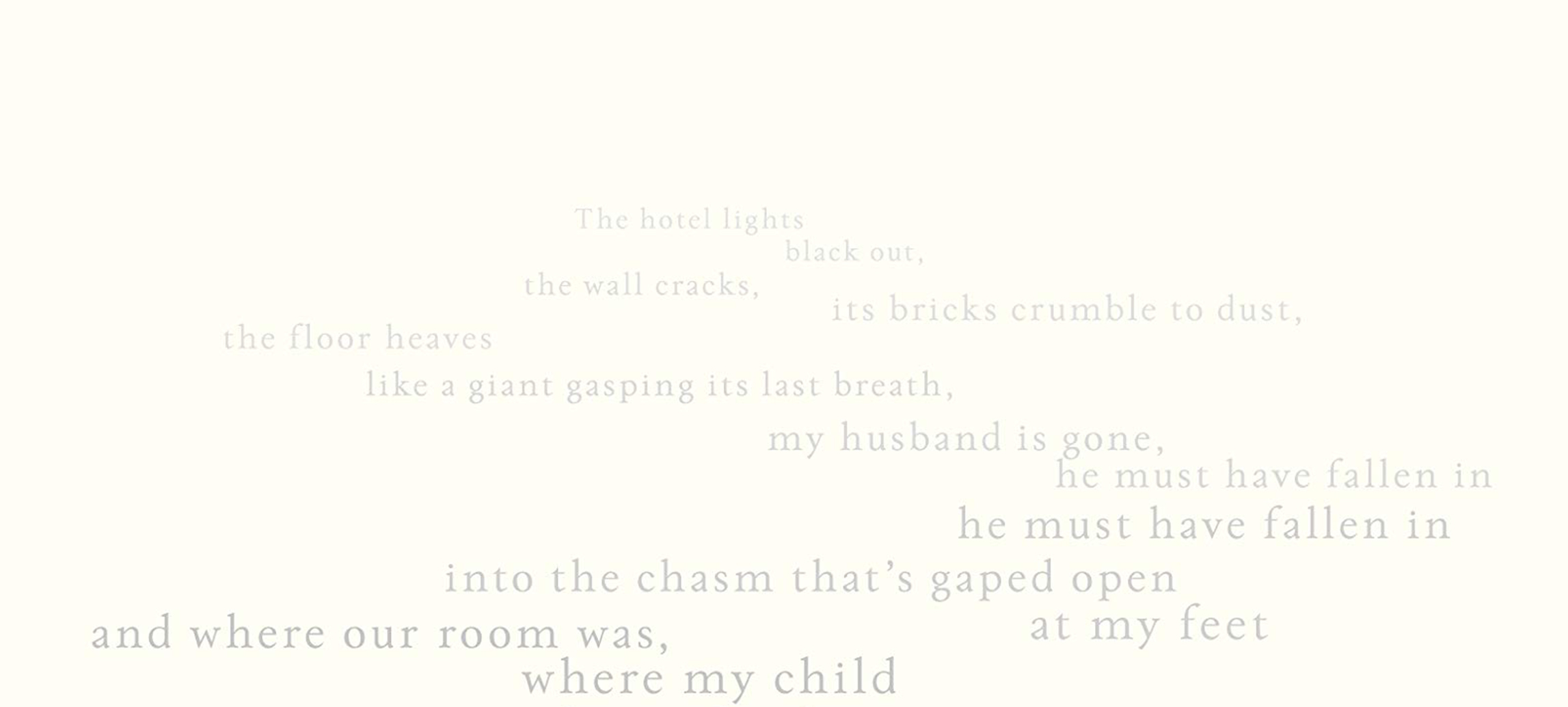

Sourcing yak milk, balancing on the top of a pole 40 ft high, using screwdrivers and Allen keys, shaving off a few millimetres on a specially sourced shoe sole, eye-tests and matching sights, excess-baggage payments carrying special equipment, the colour of a wall, the wattage of a bulb, Bollywood movies, the right meal, a mother’s love, a father’s resolve, a sister’s belief, a coach’s patience.

What have these motley elements got to do with high performance?

Most often, nothing.

And, as my own journey shows, sometimes it means everything!

Given the type of life I have led over the last twenty years, I won’t blame you for believing that I might have some secret recipe for ‘being a champion’. But honestly, I don’t. I have experimented with my diet, overcome my fears, tweaked my equipment, modified my environment and surrounded myself with the right mix of people who have challenged and supported me unconditionally.

As you can probably tell, I spent a lot of my time experimenting. Trying to be the best shooter I could be. Ask me how this shooter became an Olympic gold medallist and I will happily tell you my story. I can only hope others will find it interesting.

It is true that I have lived the quest to be perfect on the imperfect day. In doing that, I have sometimes succeeded and most times failed. It has been a journey of ups and downs from day to day, season to season, Olympics to Olympics.

Let me tell you a little about the only subject on which I can call myself an expert—myself!

Twenty-two years of competition, 180 medals, five Olympics, three Olympic finals, one Olympic gold. All of it seems a daze. Until it doesn’t.

Looking back, I can now see it all much more clinically and dispassionately. I am no longer a stakeholder in my shooting career. I have exited my investment, as venture capitalists would say. That is my past. And I have a future to think about. But that makes retrospection all the more interesting for me.

I was not a natural athlete. In fact, I was a reluctant sportsperson. Introduced to shooting by my first coach, Colonel Dhillon, I instinctively felt that this was for me. This was something I could see myself doing, making a life of and a career from. For this chance, I navigated my way from dream to reality and built the personal skills that were necessary to win. What do I consider to be the skills that made the difference?

In my early career, I was extremely focused. I was trying all I could to make a name for myself as a young shooter. Inexperience meant that my quest was for perfection, and in my mind, that objective was a stationary target. You can’t blame a shooter for that, can you? To my mind, the goal was clear and the ‘system’ a perfect one. All I needed to do was understand the system and crack the code.

Athens 2004 was a wake-up call. In perhaps the most defining incident of my career, I came a disappointing seventh in the Olympic final after shooting what I thought was the perfect game. Only much later did I find out that the lane position I was allotted had a loose tile underfoot, which reverberated every time I shot. In a game of millimetres, it was amazing that I even hit the target! I went into a depression (literally) after Athens. Months later, I had two obvious choices—one, quit the sport or, two, carry on and accept the incident as a case of ‘bad luck’. I chose a third, and it defined me.

I chose the quest for Adaptability—to try to be perfect on the imperfect day. I started training under deliberately imperfect conditions, even installing a loose tile in my home range and practising regularly while standing on it. I trained in low light and under bright lights, adjusted bulbs and added peculiar shadows, painted the walls the same colours as the relevant Olympic ranges. Extreme behaviour perhaps. But it worked for me and even came to my rescue at Rio 2016, when my carefully chosen rifle-sight, through which I focused on the target, broke just a few minutes before my event. I was able to remain composed and made it to fourth. Had I chosen option two after Athens, I would have probably accepted it as fate and given up! Did I ever again encounter a loose tile? Honestly, I don’t know, and it was not something I thought about ever again when competing. Adaptability gave me versatility and the ability to not latch on to excuses, external conditions or stimuli. My attitude changed to acceptance of the fact that the only thing within my complete control was my own performance—but I was also ready for all the rest that wasn’t!

Go! features a never-before-seen collection of essays by leading athletes, sports writers and professionals, get your copy today!