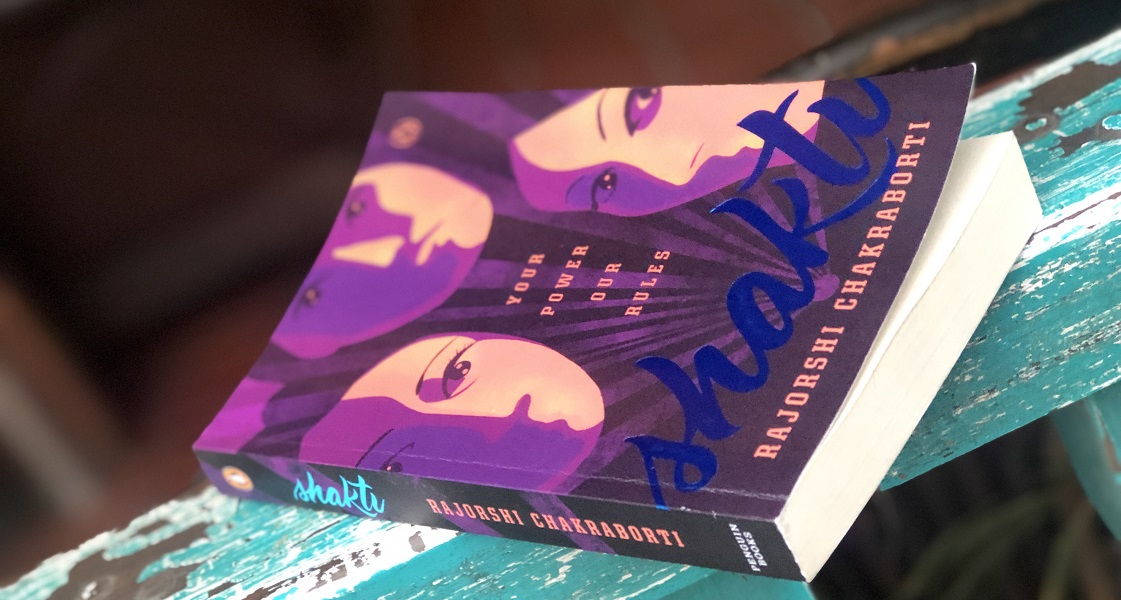

Structured as a fantastical, women-driven superhero story, Shakti by Rajorshi Chakraborti also gives us a scathing social commentary on present-day concerns of feminism, sexism, communal violence and mental health.

Through the characters of Jaya, Arati, and Shivani – three women in Calcutta who are gifted with magical powers – Chakraborti takes us on a journey across a nation that is in the throes of profound transformation. In the process, we get to glimpse a hitherto unseen country that is made up of the secrets, longings, wounds and strengths of many human hearts.

What facets of our times do we get to see in Shakti? We list some below.

Deep-rooted Communal Divides

Throughout the story, we see attempts to instigate communal violence and hatred between Hindus and Muslims; something that relates directly to our current socio-political sphere outside of the book.

An instance in the book illustrates the resulting violence due to such manipulation, where the narrator Jaya receives a Times of India link from Shivani:

“It turned out to be just a Times of India story, four paragraphs long. There had been violence in a village in Bardhaman district, about a hundred kilometres from Calcutta, where Hindus and Muslims had clashed because a Hindu boy had been found dead a few days earlier, and the belief grew that he had been punished for his sister’s friendship with a Muslim boy. Three Muslims and another Hindu had since died, including, especially sadly, two brothers of the boy, who was now in hiding. An evening curfew had been imposed on the village, and extra police had been sent from other parts of West Bengal to all likely flashpoints in the district. The final paragraph was a quote from a local opposition leader, alleging another example of a state-wide breakdown of law and order.”

School, Learning and Education

One of the narrative arcs for Jaya – the narrator of the story – also highlights some ingrained attitudes towards the syllabus and the content being taught in schools, which is expected to be restrictive and ‘nationalistic’. Jaya tells us how and why Mrs Dhanuka, the Principal of the school she teaches History in, disapproves of Jaya’s teaching:

“The [only] surprise Dhanuka threw in near the end of her tirade [was the additional charge of being ‘anti-national’! Apparently, she’d been planning to haul me in ‘even before this morning’, because of ‘the number of unhappy parents’ who’d emailed her about some of the content of our class conversations, in which, instead of ‘sticking to the syllabus’, I supposedly spent a great deal of time ‘undermining our present Prime Minister’ and also — again, to use Dhanuka’s words — ‘devaluing the heritage of our Hindu myths and epics by repeatedly insisting they couldn’t be seen as history or science’.”

Class Divides

In a fleeting but poignant incident in the book, the responses of some of Jaya’s colleagues also expose the larger lack of empathy and compassion towards the economically less privileged classes in the urban milieu.

“My shock must have been obvious, because two colleagues sitting across from me at the table asked almost immediately if something had happened. I couldn’t speak at school about how I knew Shivani (only my three closest friends knew about the column, and none of them was in the staff room), so I merely said my domestic help has been going through a wrenching personal tragedy and I can’t do anything useful. And that dissipated my questioners’ compassion even more quickly than I’d anticipated. Oh well, if it’s only something to do with your help . . .”

Struggles of the Youth

Jaya works as a columnist for an agony column to help teenagers and young adults struggling with mental health or familial issues. The narrator provides glimpses of some of her correspondences which bring to light some deep-rooted struggles that this demographic faces in the real world. Rising mental health concerns amongst the youth in India have become an important topic of discussion in the country today; and Jaya’s columns and her correspondents reflect this.

A crucial incident that speaks to this concern is Shivani’s refusal to share her emotional trauma with her family, which is why she is compelled to turn to Jaya’s column. As a fifteen-year-old, Shivani’s situation, on a microcosmic level, speaks to the pervasiveness of the lack of familial support-system and understanding that teenagers and young people face today.

Shivani writes in one of her responses to Jaya:

‘So all your concern is only from a distance. As long as you can reply by email, you care.

If you knew my parents, if you spent just half an hour in our house, you would take back the suggestion of sharing my secret with them. And without parents behind me, show me the psychiatrist who would take me seriously.’

The Power of Social Media

Social media has become a norm in the society today – especially when it comes to rebellion and mobilization. A particularly memorable incident in the story gives us a glimpse into the power of social media in (re)defining public opinion.

In one instance, Jaya – who had been writing her agony column under a male pseudonym, ‘Chandra Sir’, in an attempt to hide her true identity – is outed by a vengeful mother on Twitter. Jaya appeals to her readers to give her honest feedback about how her column impacted them. The response is overwhelmingly positive, which helps her bring back her column under her real name.

‘‘@ChandraSir is always worth reading. When the advice is good, who cares about the name? #KeepChandraSir

Police Forces

Another fleeting but poignant moment in the story makes the reader reflect on police procedures and processes. Arati – Jaya’s friend and domestic help who is also gifted with powers – attempts to confront her husband Ramesh for selling their nine-month-old daughter sixteen years ago. When he is arrested, the ease with which his bail is arranged and granted shocks Jaya:

‘‘Even greater than my amazement that a man who’d confessed to selling his own nine-month-old child could be eligible for bail was that of learning how quickly the money had been arranged.”

As a feminist superhero(ine) story we all needed, Shaktiis a highly relevant and compelling narrative for our times.