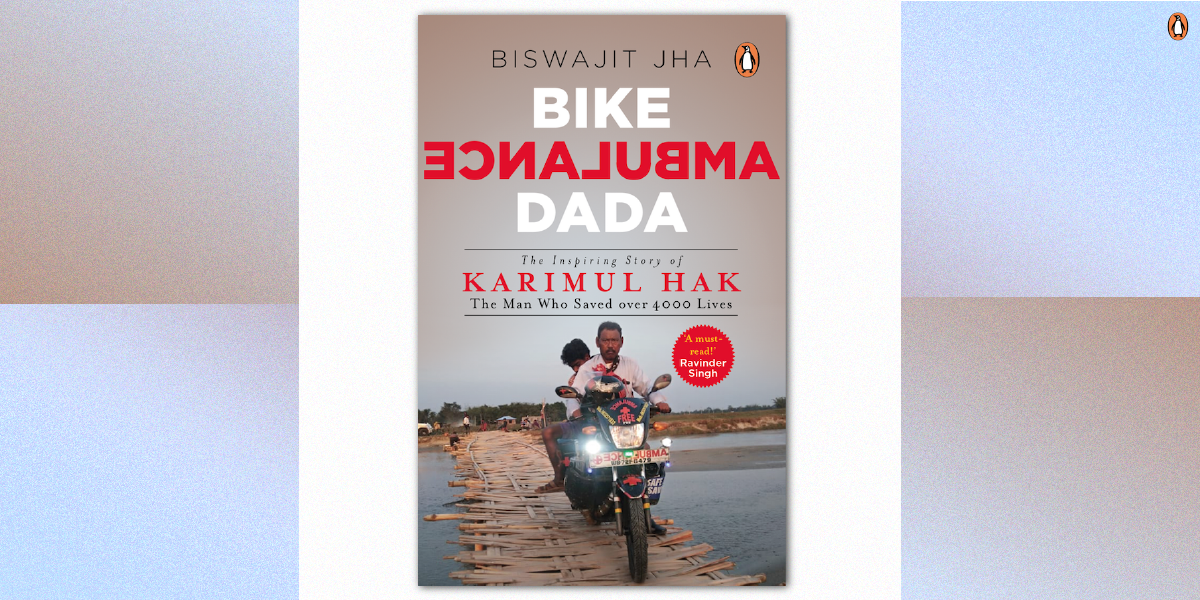

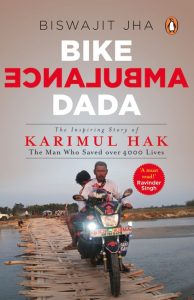

Bike Ambulance Dada, the authorised biography of Padma Shri awardee Karimul Hak, is the most inspiring and heart-warming biography you will read this year. Written by Biswajit Jha, it documents the extraordinary journey of a tea-garden worker who saved thousands of lives by starting a free bike-ambulance service from his village to the nearest hospital. The book is a must-read today as it will inspire us to do and be better in our lives.

In this interview, we talk to the author to understand his personal journey with the book and it’s story.

- Where did you come across Karimul Hak’s story?

After I quit my job and came back from Delhi in 2013 to work for the people of my area in the northern parts of West Bengal. I first read about Karimul Hak in a local newspaper and came to know the amazing story of this tea garden worker who carried critically ill patients to the hospital on his motorbike – free of cost.

- What inspired you to share this story with the world?

In 2015 when a friend of mine told me that she personally knew Karimul Hak, I felt an urge to meet this person. One day, I, along with my friend, went to meet Karimul Hak in his village much before he received the Padma Shri and much before he became a well-known figure. But I, at once, got hooked to this simple man who does such great work for the people. What amazed me is that despite being a tea garden labourer, he does such incredible work to help his fellow villagers without thinking much about his own family.

After that I started working with him to serve the poor. I made him the brand ambassador of my school which I started in 2017.

I felt people all over the world should know the story of Karimul Hak, who is living proof that you don’t have to be an extraordinary person to do extraordinary work. You can be ordinary and still do outstanding work for people. His life is an inspiration for all of us. When a tea garden labourer with a meagre monthly salary can undertake such a path-breaking journey, we all are capable of doing wonders.

- Your own father was very particular about helping others. Can you share some incidents that stuck with you?

My father, from whom I got my first lesson to serve others unconditionally, was a primary school teacher and has always led a simple and honest life. From my childhood I saw my father helping others despite the fact that he was not a rich person.

So, the lesson about doing things for others and sacrificing your own comfort for someone less fortunate than you, I got from my father who, despite being not very well-off, did everything he could in his entire life for the betterment of society. He took on a frontal role in establishing three charitable schools in our village and also worked tirelessly to improve education in and around our village. It is due to his tireless effort that we got the first English medium school in our area. I did not have to go outside my own home to find inspiration to help others.

One incident that stuck with me the most, which I also shared in the book, is a story of a sanyasi. It was a sultry summer noon in the early nineties. Hungry and exhausted, an old sanyasi came to our doorstep. My father ushered him into the puja room. After my mother fed him, the sanyasi expressed his wish to rest inside the puja room. But the room did not have a ceiling fan as we couldn’t afford one in every room. Realizing the old man might not feel comfortable without a fan, my father got the ceiling fan uninstalled from his own room and fixed it inside the puja room so that the sanyasi could sleep well.

The second incident which I remember vividly is that every year there used to take place a fair in our village. Though thousands of people would come to the fair, in those days there was no facility for drinking water in and around the fair. People would suffer due to this. Seeing the sufferings of the people, my father started to carry water in big jars from our home to the fair and started distributing drinking water along with jaggery to the people for free. I was very small at that time but my brother and I also used to go with my father and distribute water to the people. After that he made it a routine of conducting this ‘water camp’ every year. This is another lesson I learnt from my father that whenever you see people suffering, you should come up with some sort of solutions in your capacity.

- What was the book-writing experience for you? Particularly knowing you’ve always wanted to write?

I always wanted to write a book. But I did not know when that would actually happen. As I am a social entrepreneur and not a full-time author, writing a book was very challenging. Taking out time from my busy schedule was a challenge. After quitting journalism, I stopped writing for almost two years. That actually helped me. My urge for writing increased manifold during these two years.

When I had started working with Karimul Hak, I felt an urge to take this story to the people all over the world and inspire them. When you have such a mission to accomplish, no job in world seems a challenging. Rather, I enjoyed writing this story. I enjoyed knowing Karimul Hak more closely while researching for this book, talking to him and interacting with people of his close quarters. I was so engrossed with the struggles of his life that I cried several times while writing his story.

- What was the biggest challenge in this project?

There were many challenges I faced while writing this book. The biggest challenge was to make Karimul sit and talk. Since he can’t sit for more than 10/15 minutes in a single place, listening to the stories of his life from him was a challenging task. Apart from that he does not remember many incidents of his life. He would keep on telling me only 5/6 stories of his life which were not enough to write a book. Getting information about Karimul’s childhood days was also a challenge. Apart from that I had to write within certain parameters while writing a biography or a real life story. But I wanted this book to be interesting to the readers also so that it does not become monotonous. So, writing a non-fiction in a fictional way was a challenge but I tried to keep that ‘tension’ alive throughout the book.

- What made you switch professions, from a journalist to a social entrepreneur?

Like Karimul, I was also born and brought up in a humble family of a small village in Jalpaiguri district of West Bengal. I struggled my way into becoming a national level journalist. I hardly got any support while I grew up. But I wanted that no one should face the same ordeal which I faced in my childhood.

With this thought in mind, me and my wife both quit our jobs and well-settled life in Delhi and came back to my roots in the northern parts of West Bengal which is considered to be the backward area of the state. After that we started serving the poor and helpless people. I basically wanted to be a part of the difficult but successful stories of many struggling men like Karimul.

Apart from many other social activities I am involved in right now, writing this book on this unsung hero is one of my ways of giving back to the society.

- How satisfying has the change been and what changes have you experienced in yourself after this switch?

Initially, it was very challenging. To start everything all over again was very tough. I had many sleepless nights. But I kept on doing good for the others in my tough days. That, I think, helped me overcome my personal troubles. When I found that there were thousands of people who did not have basic things like food, clothes and shelter, my problems seemed much lesser compared to theirs.

While working for the others, I became a much better person. I found my true meaning of life. I felt happy within. And when you start to feel happy within, everything around you becomes beautiful. That’s why in my second book, which is a fiction and will be published after my debut book Bike Ambulance Dada, I wrote that the only way to get happiness is to serve others unconditionally.