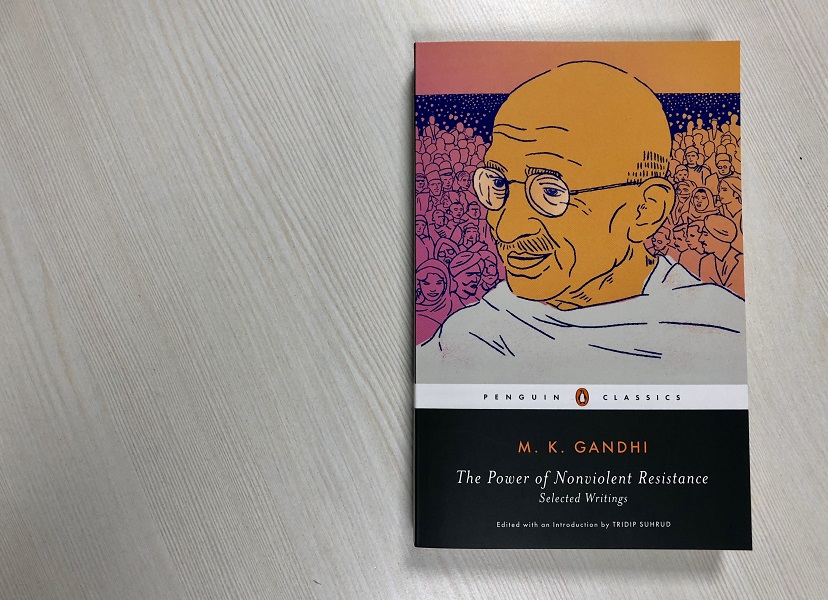

‘Where there is love there is life.’ – Gandhi

With the new year round the corner, take the time to read The Power of Nonviolent Resistance: Selected Writings , a specially curated collection of Gandhi’s writings on nonviolent resistance and activism.

Read an excerpt from the book below:

—

Toward the end of his life, Gandhi was asked by a friend to resume writing his autobiography and write a “treatise on the science of ahimsa.” What the friend wanted were accounts of Gandhi’s striving for truth and his quest for nonviolence, and since these were the two most significant forces that moved Gandhi, the friend wanted Gandhi’s exposition on the practice of truth and love and his philosophical understanding of both. Gandhi was not averse to writing about himself or his quest. He had written—moved by what he called Antaryami, the dweller within, his autobiography, An Autobiography or the Story of My Experiments with Truth. Even in February 1946 when this exchange occurred he was not philosophically opposed to writing about the self. However, he left the possibility of the actual act of writing to the will of God.

On the request for the treatise on the “science of ahimsa” he was categorical in his refusal. His unwillingness stemmed from two different grounds: one of inability and the other of impossibility.

He argued that as a person whose domain of work was action, it was beyond his powers to do so. “To write a treatise on the science of ahimsa is beyond my powers. I am not built for academic writings. Action is my domain, and what I understand, according to my lights, to be my duty, and what comes my way, I do. All my action is actuated by the spirit of service.” He suggested that anyone who had the capacity to systematize ahimsa into a science should do so, but added a proviso “if it lends itself to such treatment.” Gandhi went on to argue that a cohesive account of even his own striving for nonviolence, his numerous experiments with ahimsa both within the realms of the spiritual and the political, the personal and the collective, could be attempted only after his death, as anything done before that would be necessarily incomplete. Gandhi was prescient. He was to conduct the most vital and most moving experiment with ahimsa after this and he was to experience the deepest doubts about both the nature of nonviolence and its efficacy after this. With the violence in large parts of the Indian subcontinent from 1946 onward, Gandhi began to think deeply about the commitment of people and political parties to collective nonviolence. In December 1946 Gandhi made the riot-ravaged village of Sreerampore his home and then began a barefoot march through the villages of East Bengal.

This was not the impossibility that he alluded to. He believed that just as it was impossible for a human being to get a full grasp of truth (and of truth as God), it was equally impossible for humans to get a vision of ahimsa that was complete. He said: “If at all, it could only be written after my death. And even so let me give the warning that it would fail to give a complete exposition of ahimsa. No man has been able to describe God fully. The same hold true of ahimsa.”

Gandhi believed that just as it was given to him only to strive to have a glimpse of truth, he could only endeavor to soak his being in ahimsa and translate it in action.

The Power of Nonviolent Resistance: Selected Writings by Gandhi gives context to the time of Gandhi’s writings while placing them firmly into the present-day political climate, inspiring a new generation of activists to follow the civil rights hero’s teachings and practices. The book is available now!

Mishki and Pushka have learned a lot about India. And now they’re ready to solve the puzzles, riddles and activities that Daadu Dolma has created specially for them.

Mishki and Pushka have learned a lot about India. And now they’re ready to solve the puzzles, riddles and activities that Daadu Dolma has created specially for them.