As the world once again confronts an eruption of authoritarianism, Gyan Prakash’s Emergency Chronicles takes us back to the moment of India’s independence to offer a comprehensive historical account of Indira Gandhi’s Emergency of 1975-77. Stripping away the myth that this was a sudden event brought on solely by the Prime Minister’s desire to cling to power, it argues that the Emergency was as much Indira’s doing as it was the product of Indian democracy’s troubled relationship with popular politics, and a turning point in its history.

In this interview, he talks to us about writing the book!

How long was the research process for this book?

I began research in 2012 and continued it right up writing the first draft of the manuscript, that is, until the end of 2017.

What are some of the archival sources you looked through for this book?

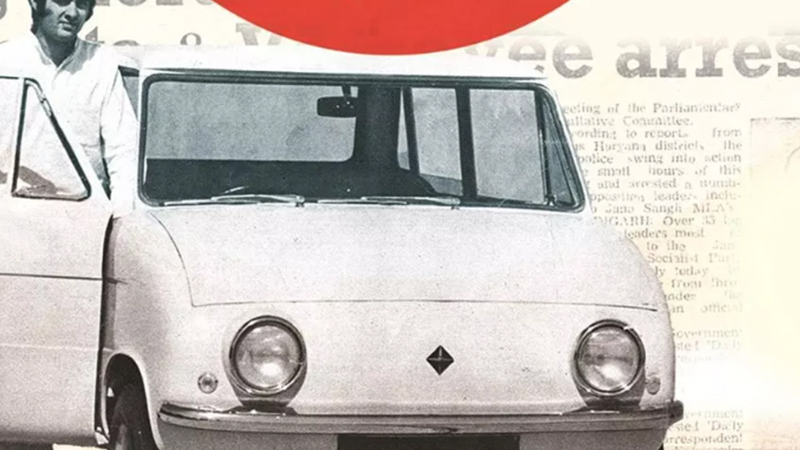

The core of my archival research was at the National Archives of India and Nehru Memorial Museum and Library. Much of the research at NAI consisted of the depositions before the Shah Commission. While the published report summarized the Commission¹s findings, the depositions proved to be a treasure trove in composing a picture of the daily functioning of the Emergency. The private papers at NMML were invaluable in fleshing out the thoughts and activities of the individual actors. In addition, I trawled through the records of Ford Foundation at the Rockefeller Archive Center in New York to uncover the stories of pre-Emergency family planning and urban slum clearing programs. I chanced upon an unexpectedly rich archival resource consisting of prison letters in the collection of the Center for Research Libraries, Chicago. In addition, I searched through motor car archives in the UK to get materials on the Ambassador since Hindustan Motors claimed that they had none.

In your view, what is the biggest misconception about the Emergency?

The biggest misconception about the Emergency is that it emerged out of nowhere, attributable solely to Indira Gandhi’s desire to cling to power, and that it disappeared without a trace after 1977. This is a comfortable myth because it permits Indians to believe that there are no deeper problems with India’s experience with democracy, and thus no long-term effects. Since this appeared patently implausible to me as a historian, I set about placing these 21 months in a longer historical perspective, examining both its antecedents and its afterlife.

What is some of the criticism you’re expecting to get for this work?

I expect that those who think that Indira, along with her coterie, as the sole cause of the Emergency would think, wrongly, that the book excuses her. I do not minimize her role, or that of her son, Sanjay; instead, I suggest that Indira did not function in a vacuum. What she and her coterie did was to ratchet up by few notches policies and projects that were long in the making.

What are some of the differences our country would have today, if the Emergency hadn’t been declared?

I think that the political crisis of the early 1970s existed prior to, and independent of, the Emergency. What the suspension of rights did was to turn a political crisis into a constitutional crisis. This produced the belief that Indira was only problem for Indian democracy, and that all that was needed was to restore constitutional rights This prevented a full reckoning with the underlying crisis of democracy and governance that she had tried to salvage through the declaration of Emergency. Without it, perhaps India would have confronted more squarely its failure to realize the promise of democracy as a value.

In Emergency Chronicles, Gyan Prakash explains how growing popular unrest disturbed Indira’s regime, prompting her to take recourse to the law to suspend lawful rights, wounding the political system further and opening the door for caste politics and Hindu nationalism.