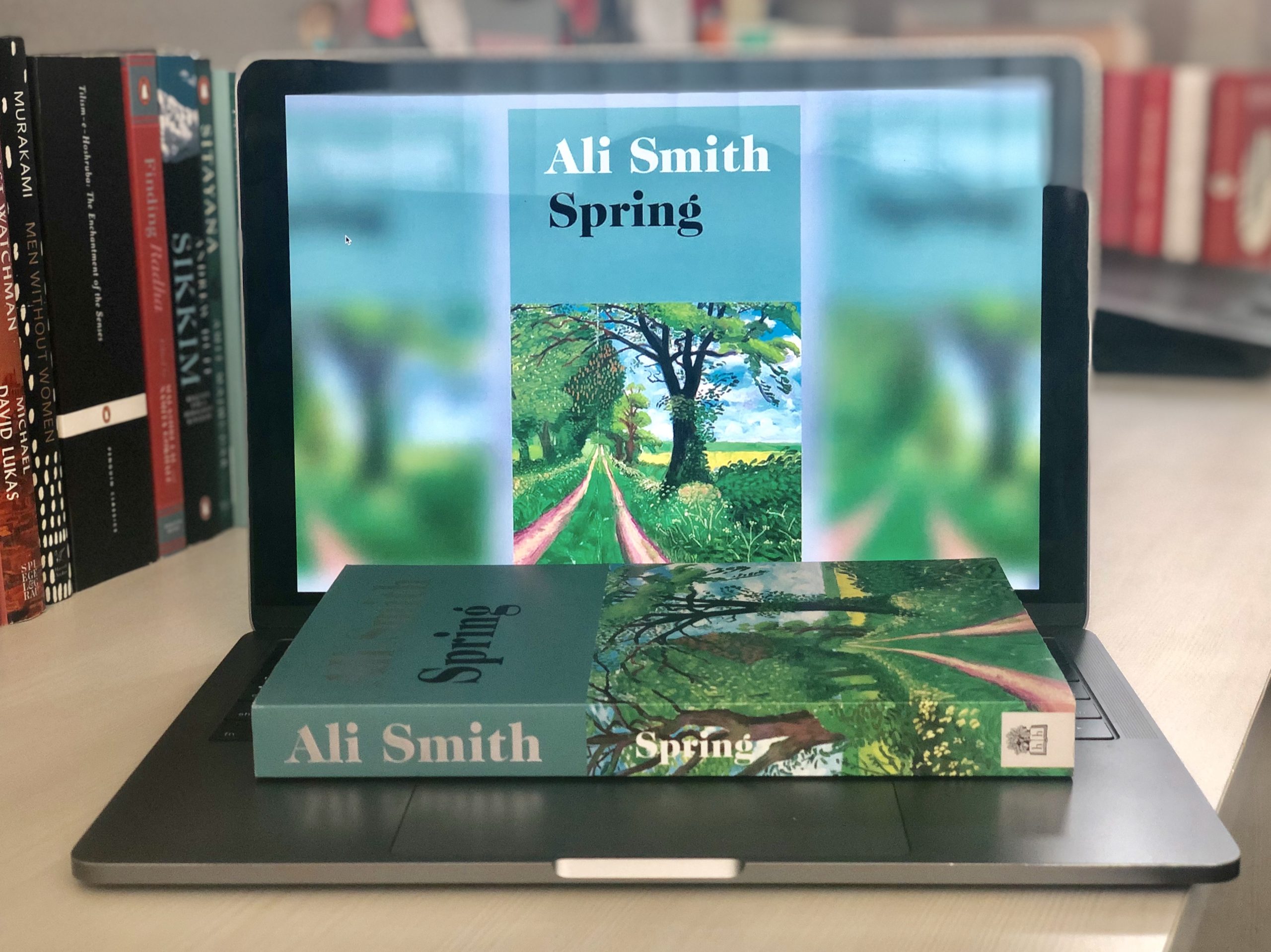

Spring will come. The leaves on its trees will open after blossom. Before it arrives, a hundred years of empire-making. The dawn breaks cold and still but, deep in the Earth, things are growing.

Yesterday morning, a month to the day since the memorial service (they’d had her privately cremated some time before the memorial, he doesn’t even know when, close family only), he is walking along the Euston Road and as he passes the British Library he sees a woman sitting against its wall, thirties, as young as twenties, maybe, blankets, square of cardboard ribbed off a box on which there are words asking for money.

No, not money. The words on it are please and help and me.

He’s passed countless homeless people even just this morning coming through the city. Homeless people are the word countless again these days; any old lefty like him knows that this what happens. Tories back in, people back on the streets.

But for some reason he sees her. The blankets are filthy. The feet are bare on the pavement. He hears her too. She is singing a song to nobody – no, not to nobody, to herself – in a voice of some notable sweetness, at a quarter to eight in the morning.

It goes:

a thousand thousand people

are running in the stre-eet

oh nothing nothing nothing

oh nothing nothing nothing

oh nothing

Richard keeps going. When he stops keeping going he is just past the front of King’s Cross station. He turns and goes in, as if that’s what he meant to do all along.

There is a stall in the middle of the concourse beneath the giant Remembrance poppy. The stall is selling chocolate in the shapes of domestic utensils and tools: hammers, screwdrivers, pliers, cutlery, cups and so on; you can buy a chocolate cup, a chocolate saucer, a chocolate teaspoon and even a chocolate stovetop espresso-machine (the stovetop machine is costly). The chocolate things are extraordinarily lifelike and the stall is thronged with people. A man in a suit is buying what looks like a real kitchen tap, made of silver-sprayed chocolate; the woman selling it to him places it delicately into a box she first lines with straw.

Richard puts his card into one of the ticket machines. He inserts the name of the place that’s the furthest a train from here can go.

He gets on to a train.

He sits on it for half a day.

An hour or so before the train reaches this final destination he’ll see some mountains against some sky through the window and he’ll decide to get off the train at this place instead. What’s to stop him doing what he likes, getting off at a place not printed on the ticket?

Oh nothing nothing nothing.

King Gussie, to rhyme with fussy, is how he’d always thought it was said, like the robot announcer pronounces it over the speakers in London King’s Cross above his head before he boards the train.

Kin-you–see is how it’s said by the guest house people whose door he knocks on when he gets there. They will be suspicious. What kind of person doesn’t book ahead on his phone? What kind of person doesn’t have a phone?

He will sit on the edge of the strange bed in the guest house. He will sit on the floor and brace himself between the bed and the wall.

By tomorrow his clothes will have taken to the air-freshener smell of the room he’ll spend the night in.

Get a copy of Ali Smith’s Spring here!