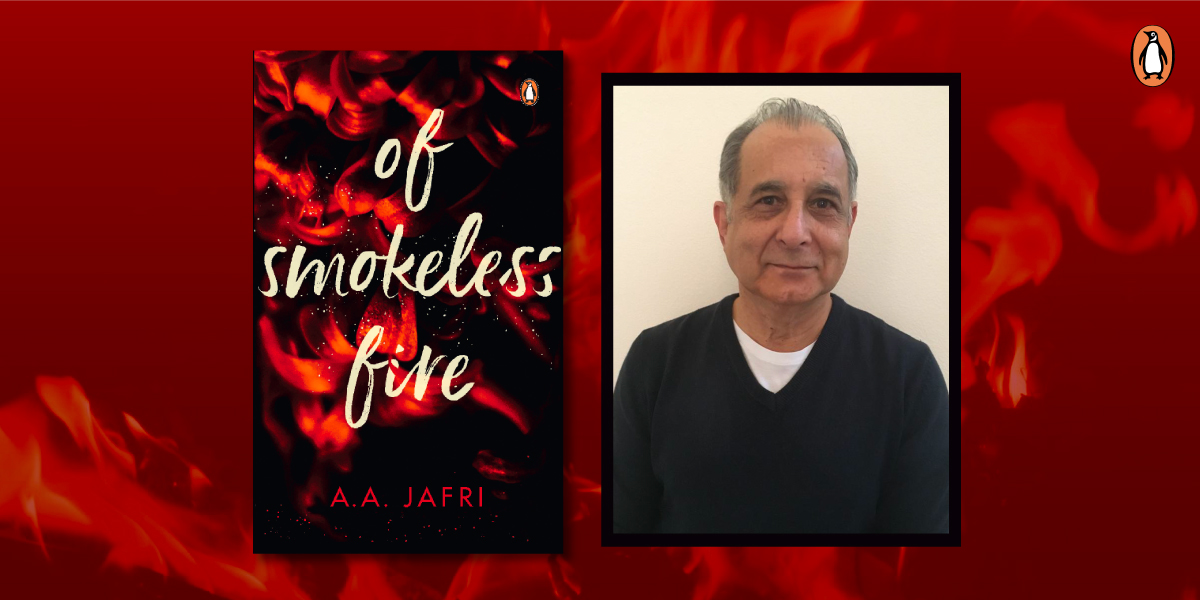

A.A. Jafri was born and raised in Karachi, Pakistan. He is an economist by day and a writer by night. Of Smokeless Fire is his first novel.

We caught up with him and asked him a few questions that really intrigued us. Keep reading to find out his answers.

~

Of Smokeless Fire

A.A. Jafri

Of Smokeless Fire was your first published book, was it also your first attempt at writing one?

I started writing from a very early age, first with poetry and then short stories in Urdu. Initially, I think it was an exercise in self-discovery, a stream of consciousness experience without much structure or order. This novel was the first time I wrote in a serious, sustained way. So, yes, this is my first attempt at writing with the hope of getting my work published.

How was writing this book as an experience for you? Do you plan on writing and publishing more works in the future?

For me, writing Of Smokeless Fire has been a joyous journey. It has given me a sense of perspective, a place to give voice to my thoughts, memories, and reflections. Writing this novel has also been an incredibly cathartic experience, providing me with the means to revisit Pakistan’s complicated history and delve into the aftermath of the partition of India that my parents’ generation experienced. By creating and recreating characters and situations, it has helped me frame some uncomfortable questions.

As for the future, I’m writing a prequel to Of Smokeless Fire, imagining the life Noor ul Haq, one of the novel’s protagonists in the story, led in pre-partition India. What made him who he was? And why was the sense of belonging and displacement so pronounced in his life? While my present novel, among other things, explores the relationship between Noor and his son Mansoor, the prequel examines Noor’s relationship with his father.

You’re an economist who deals with facts and figures all day, what compelled you to write fiction?

Behind facts and figures, there are always stories of human beings—how people live, how they scrape a living, and how they die. I have always questioned the way professional economists have dealt with human problems. My interest in economics has always been related to issues of poverty and economic development. John Steinbeck wrote The Grapes of Wrath about how families got uprooted by the Great Depression. Charles Dickens’s Hard Times is about the social and economic conditions of the early industrial age and how it dehumanized workers. Fiction sometimes explains economics better than professional economists. I often imagine the “what-ifs” of policies. Although my novel raises questions about alienation and belonging, I hope it also reveals deep-seated economic issues and issues of class and gender in our society. I’m compelled to write the human interest behind these issues.

Is the story in fact, purely fiction, or are there bits and pieces drawn from life and experience?

I can’t envision any story as solely fiction; it has to emulate lived experiences and invent replications. My novel is, of course, a fabrication, but it also draws from people I met or knew or heard about, the conversations I eavesdropped on, the fleeting encounters with strangers, the myths I grew up with, the rumors that circulated. I have tried to retrieve all those memories—real or fantastic—and applied them to a concocted reality, imagining the what-ifs and trying the why-not. The change of fortunes in Joseph’s and Mehrun’s lives—the servants’ children—in Of Smokeless Fire is fictitious but inspired by stories of real people who broke out of the cycle of grinding poverty.

The lines from the Qur’an that serve as an epigraph to Part I of the book are rather significant. What made the ‘djinn’ so central to your plot while you conceptualised your story?

I grew up listening to stories about djinns and reading about their existence in the Qur’an. I knew many who believed in a literal interpretation of djinns, while others explained them metaphorically. Opinions about the sacred often become such a steadfast belief that no amount of fact or logic can shake that certainty. Even followers from the same faith have conflicting views about such beliefs. It is like you are speaking a different language in the chaos of contrasting opinions. I felt that such disjunctions needed to be told in a story. So often, disparate explanations create an interesting plot, bringing in contradictions, contempt, and cruelty. I wanted to capture all that in my novel.

In my story, Noor explains what the word djinn means. It is something hidden, the part of everyone’s self that’s concealed, even from our own selves. According to him, one needs to discover that reality. He tells his son that if he finds his inner djinn, he will find his true self. My book explores the internal struggle that one has with oneself.