How did India aspire to become a secular country? Given our colonial past, we derive many of our laws and institutions from England. We have a parliamentary democracy with a Westminster model of government. Our courts routinely use catchphrases like ‘rule of law’ or ‘natural justice’, which have their roots in London.

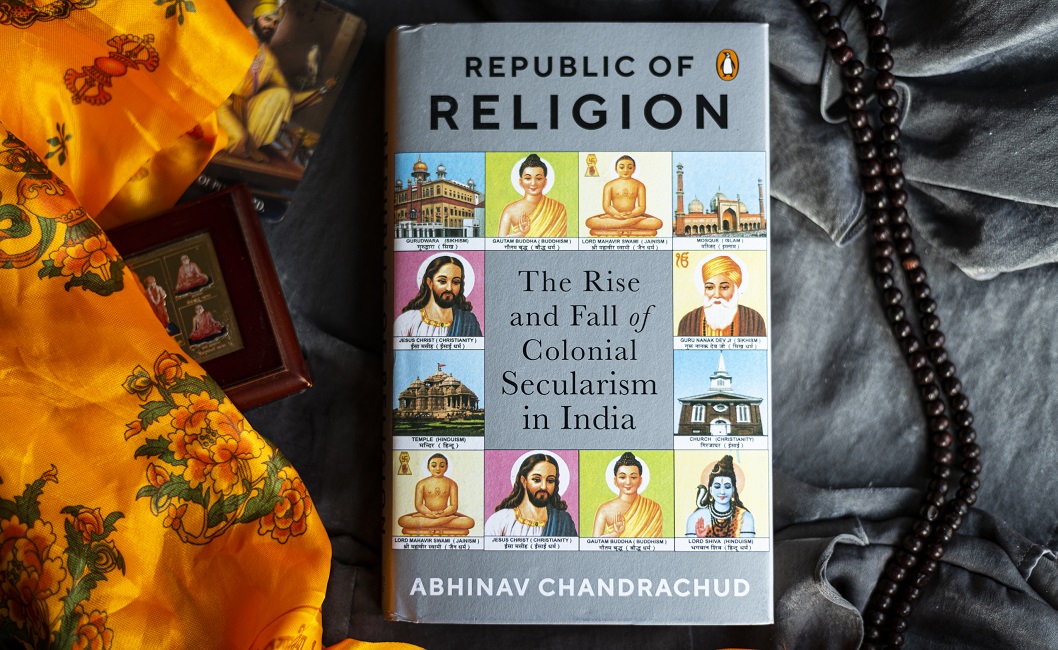

In Republic of Religion, eminent scholar Abhinav Chandrachud presents well-researched reasons to argue that the secular structure of the colonial state in India was imposed by a colonial power.

Find an excerpt from his narrative that sets up this argument while exploring the nuances of secularism as a concept.

Though scholars disagree on the meaning of secularism, broadly speaking, two factors go into making a secular state: no religion should be established by law as the official state religion and all citizens should have the freedom to practise their own religious beliefs.7 Unlike the US, England has an established religion. If India derives so many of her laws and institutions from England, how is it that there is no established religion in India?

In the coming pages, we will see that secularism was artificially imposed by the British colonial government in India even though it did not fully exist in England. The law in England assumed only Christianity to be the one true religion, and Indian religions like Hinduism and Islam were considered to be ‘heathen’. Therefore, though England had an established religion—Christianity through the Church of England—it could not declare an Indian religion, like Hinduism or Islam, as the official religion of India. It could not force Christianity on India probably due to the fact that this would have made the colony ungovernable.8 Instead, it decided to separate religion and the state in India. Though government officials in England were entangled with the administration of churches there, colonial officials felt uncomfortable associating with ‘false’ Indian houses of worship like temples and mosques and therefore assigned them to the administration of Indian trustees.

British officials adopted a policy of secularism in India—in contrast to England—which will be referred to here as ‘colonial secularism’. Though ‘secularism’ is itself a relatively new9 word and one of imprecision,10 broadly speaking, colonial secularism in British India meant that the government did three things. Firstly, the colonial state would not endorse or get itself entangled in the administration of any local religions. So it disentangled itself from the management of temples—a function which was historically performed by Indian rulers—and handed temple administration over to trustees. This was despite the fact that a parallel nineteenthcentury campaign to disestablish the Church of England failed in the metropole.11 Further, before taking up office, public officials in India were made to solemnly swear or affirm their oaths, though they might have had no conscientious objection to swearing in the name of God, Vishnu or Allah. In other words, any mention of the word ‘God’ was removed from the oaths administered to public officials in India—an accommodation which was only available to Quakers and some others in England. Secondly, the colonial state provided heightened protection to religious minorities, often feeding into a sense of paranoia that they would be left helpless without its imperial

intervention. So the personal laws of different religious groups were, in theory,12 left alone,13 though England did not have a separate set of ‘personal’ laws for its religious minorities like Catholics and Jews. Adopting the old Roman strategy of retaining the laws of conquered territories in order to make them more easily governable, colonial officials decided against adopting a uniform civil code in family law matters. Cow slaughter, though reviled by much of India’s majority Hindu populace, was permitted to be carried out by Muslims during the festival of Bakr Id and Hindus who objected to it were considered ‘hypersensitive’. Seats on legislative bodies were filled by voters on the basis of separate electorates. Thirdly, the government tacitly, though nervously, encouraged Christian missionaries to preach Christianity and obtain converts though a Hindu or Muslim preacher who might have tried to do the same in England would have put himself at risk for criminal prosecution.

Secularism is one of the most celebrated ideals of a diverse India. Republic of Religion is a unique narrative presenting a never-before explored perspective and colonial ties that can potentially lie behind this term.