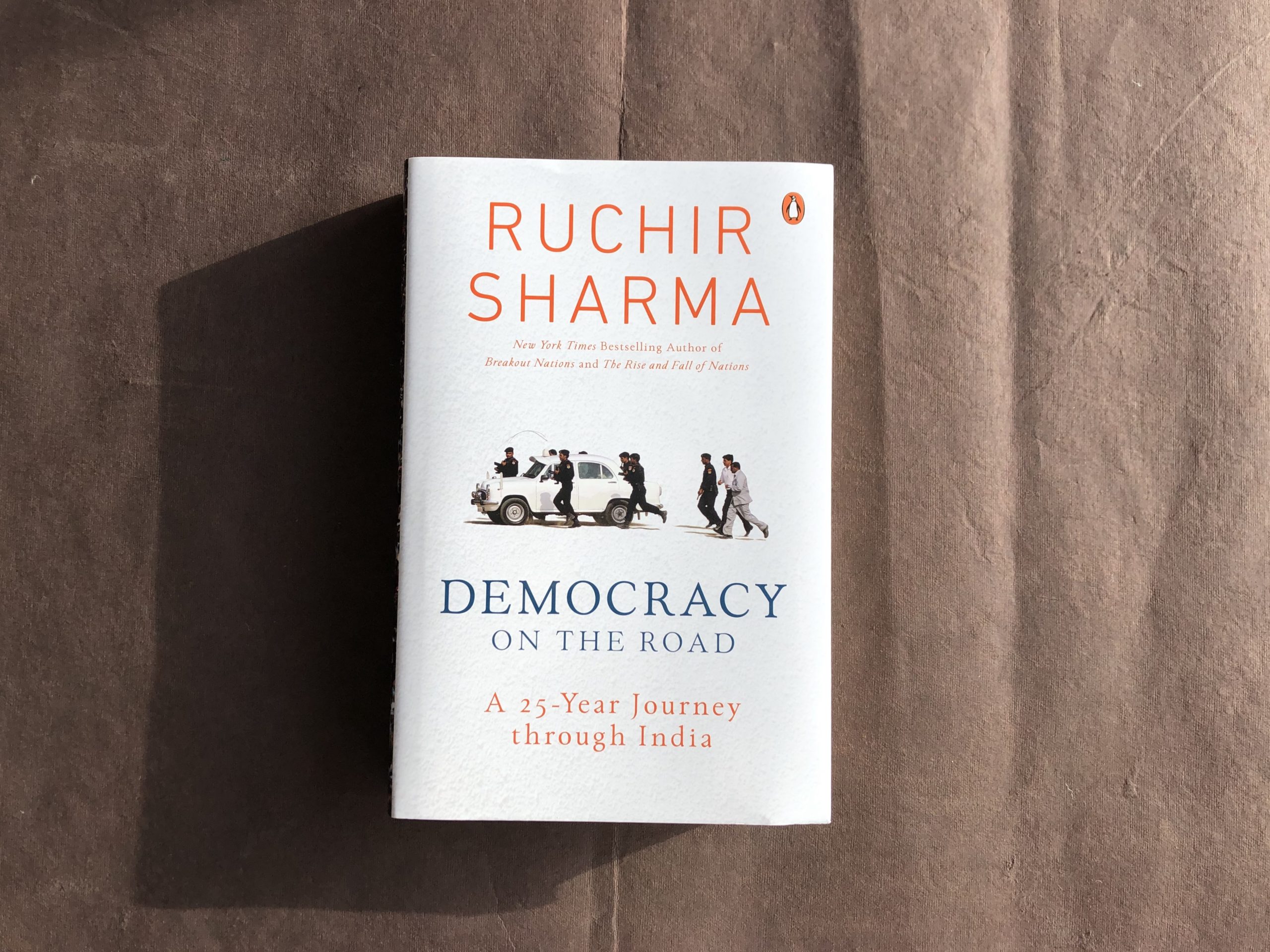

On the eve of a landmark general election, Ruchir Sharma offers an unrivalled portrait of how India and its democracy work, drawn from his two decades on the road chasing election campaigns across every major state, travelling the equivalent of a lap around the earth.

In this excerpt from his book, Democracy On The Road, Ruchir Sharma talks about Jaya Prada’s election contest against Noor Bano in the 2009 elections.

We found yet another spin on the byzantine turns of Indian alliance politics unfolding in the city of Rampur, best known for its Mughlai cuisine, lilting poetry and Rampuri chakus—the long knives once favoured by small-time villains in Hindi movies. As we often do we arranged a meeting with the DM, the district magistrate, and outside his office I noticed a wooden board listing all the previous DMs of Rampur.

The list ran long, implying that the tenure of any one DM was quite short—likely because state governments come and go so quickly, and each new ruling party brings its own roster of local officials. I asked the DM about this and he said with a wry smile that Hinduism recognizes four sequential stages of life, from Brahmacharya (student), Grihastha (householder), Vanaprastha (retired) and finally Sannyasa (renunciation). But the life of a district magistrate bounces between these stages in no apparent order, and they ‘can never be sure which will come next’.

In Rampur, Congress candidate Noor Bano, a scion of Rampur’s royal family, was plotting her comeback against the former film star Jaya Prada, whose rootless career symbolized the fluid loyalties of Indian politics. We met Jaya Prada in a luxury suite at The Modipur Hotel, itself a classically Indian mash-up of garishly colourful decoration and gold-plated religion, with miniatures of Hindu gods dotting the makeshift dining-room temple where Jaya Prada prayed.

Jaya Prada had been a coveted ally not for her Hindu piety or her caste but for her multilingual celebrity: she was the rare actress who had starred in both Telugu and Hindi films. After appearing in more than 300 movies over three decades, she became a favourite of Chandrababu Naidu and later a member of parliament representing his Telugu Desam Party in the Rajya Sabha.

Then she not only switched parties, she switched to a new state and a capital city nearly 1500 kilometres away. After falling out with Naidu she had left his party in 2004 and accepted an invitation to join Mulayam Singh Yadav’s Samajwadi Party in UP. Milling about Jaya Prada’s expansive hotel suite in Rampur we found a mix of her relatives and their kids, Samajwadi Party functionaries and Muslim clerics—all moving around carefully so as not to knock over the Hindu statuettes.

Asked how her transition across state, party and religious lines had gone so far, Jaya Prada smiled and said, ‘AP+UP=JP’, or Andhra Pradesh plus Uttar Pradesh equals Jaya Prada, the kind of formula that could describe the hybrid backgrounds of many itinerant Indian politicians.

There were, however, signs of strife. Some Samajwadi Party members appeared to be secretly manoeuvring to tar Jaya Prada as an immoral ex-starlet, apparently as punishment for showing insufficient respect to their local party boss, the Muslim leader Azam Khan. Though Jaya Prada carried herself with cinematic aplomb, her optimistic glow did crack once—when she described these machinations against her.

She was particularly upset about photos that had surfaced online, doctored to show her in compromising poses. Leaving the interview we made our way past Bollywood movie star and Rajya Sabha member Jaya Bachchan, who had flown in to campaign for Jaya Prada and appeared quite angry that a bunch of journalists had kept her waiting.

Next we went to see the Congress stalwart whom Jaya Prada unseated back in 2004, Noor Bano, and found her dressed sari-tosandals all in pure white, but dark with resentment at losing her Lok Sabha seat to this film industry interloper from Andhra Pradesh.

Bano, seventy, pitched herself as the opposite of a ‘shifty’ ex-actress: as a daughter of Rampur royalty, she was not a migrant politician and could be relied on to remain true to the locals. Whatever progress the Rampur area had enjoyed of late had nothing to do with Jaya Prada or the Samajwadi Party, Noor said. It was all the work of the national government under Prime Minister Manmohan Singh, which had done so much for farmers and the poor.

The most uplifting thing about the Jaya Prada versus Noor Bano battle was that it pitted two women against each other, in a country where women had been rising in politics but at a painfully slow rate. The number of women in the Lok Sabha had risen from just nineteen in 1977 to fifty-nine here in 2009, and we had seen how the constant struggle to command respect in a male-dominated political culture had left many prominent female leaders battle-hardened and suspicious, including supremos like Jayalalithaa and Mayawati. The one clear thing about the Rampur contest was that a woman would win, and be beaten by a woman.

Democracy on the Road takes readers on a rollicking ride with Ruchir and his merry band of fellow writers as they talk to farmers, shopkeepers and CEOs from Rajasthan to Tamil Nadu, and interview leaders from Narendra Modi to Rahul Gandhi.