*

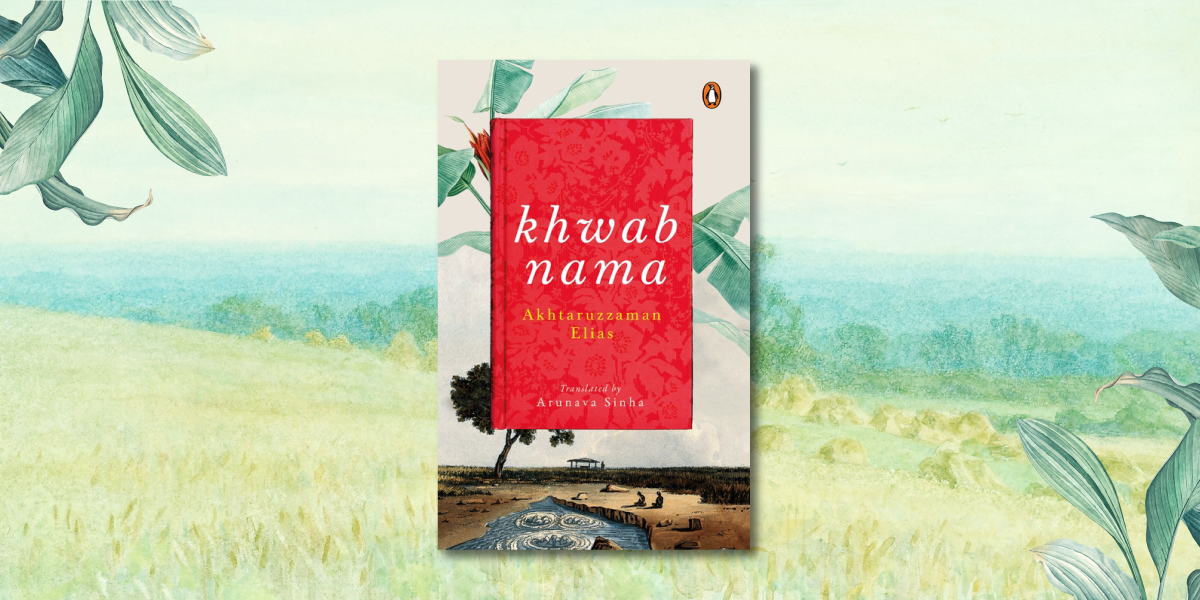

Khwabnama

Akhtaruzzaman Elias

All these memories from long ago, the exuberance from the past, the happiness before the famine—all of them surged through the troubled times that had passed since then to bubble up in Kulsum’s heart. She had not given birth to a child from her own womb. So whether you talked of a son or of a daughter, Tamiz was both of these for her. When this surge of emotion spilled out of her heart, her entire body thrilled to it, and to escape this infestation she suddenly grew desperate to find fault with Tamiz. But then she was an illiterate woman, the daughter of a fakir; how was she to find a flaw in the strapping young man that Tamiz was? Instead, she took advantage of Tamiz’s father sleeping like the dead to steal some of his anger with his son and taste it—do you have to go to Khiyar in search of work? But there was less and less of work to be had with every passing day, this was true too. Not too long ago, even eleven or twelve years ago, old-timers used to say, sowing, weeding, reaping—all sorts of jobs were available right here in Girirdanga and Nijgirirdanga, on both sides of the lake. Apparently there weren’t enough people looking for work then. And in case something needed to be done at short notice, Pocha’s son Kasimuddi, who lived across the lake, had to be sent for. He was as stupid as his father, didn’t own even a sliver of land, and lived in other farmers’ huts or cowsheds or verandas. People would beg and plead with him when they needed a tree trimmed or a house repaired. And look, since then a thousand Kasimuddis had sprung up in every direction. All the bastards were in search of work. So many people died in the famine, so many more sold their house and land and went away, but still the number of people never decreased. All those who had sold their land and house but not left the village were desperate to work as hired hands. But where was the work? Earlier the sharecroppers hired daily labourers, but now they even set their own babies in arms to work in the fields. All right, all understandable. What choice did Tamiz have but to go to Khiyar for work? But consider what his father was saying, consider it well. Why all this flirtation with women when you go to Khiyar? Tamiz’s father knew everything, Kulsum could imagine too, they weren’t good people over at Khiyar. Whenever they spotted young men, working men, they set their daughters to trap them. They got their daughters to marry these men and then kept them in their own homes, forcing the grooms to work on the land that they had taken on lease, to look after the cattle, to build their houses for them. Kneading clay and making walls with it was hard work. The young men became permanent members of their families. The witches cast their spells and the men passed their entire lives as their slaves, not even remembering their own parents any more. A man settling down in his wife’s home—the whole thing suddenly appeared intolerable to Kulsum. Not for nothing had Tamiz’s father become despondent. Let me tell you, he was no ordinary man. No one knew whose call he answered in his sleep when he walked out at night, or where he went, or how far. People said so many things about Tamiz’s father, but no matter what he did in his sleep, there was no match for him when it came to hard work. It was the people of Majhipara who used to enjoy the fish that Tamiz’s father caught in Katlahar Lake before it passed into Sharafat Mondol’s control. Back then Tamiz’s father could snare carp weighing 6 or 7 seers each even with his ripped fishing net. Those little nets would often sink to the bottom of the lake under the weight of the fish, forcing him to wade neck-deep into the water to reel the net back in. The veteran fishermen would say, ‘You’d better be careful going in there. All the fish come running when you cast your net. Not a good sign.

**

Read Khwabnama to understand the many layers of the Tebhaga movement and to appreciate Elias’ writing style and thematic structure of the novel.