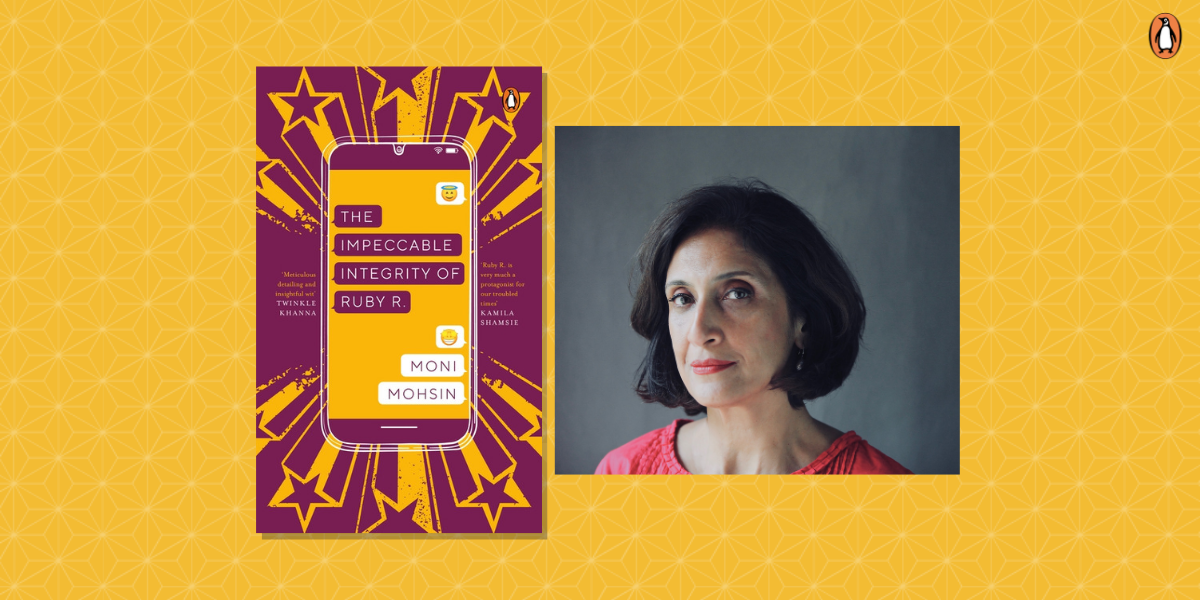

Moni Mohsin sat with us for an absolutely delightful chat, and we just can’t get enough of her (and her book The Impeccable Integrity of Ruby R of course!)

South Asian literature has historically been seen as heavy and weighted, so do you feel a little more liberated working with a freer style like satire?

MM: It’s not that satire is lighter per se because you can go to really dark places with satire too. I choose to write social commentary that allows me to portray my society as accurately and as truthfully as I can while also exploring its more comedic side.

If you had to pick five desert island reads, they would be:

MM: Ah! This is a difficult one not least because my essential reading keeps changing, but if I have to give you top five today they would be:

George Eliot’s Middlemarch because it is so wise, profound and capacious.

Digging to America by Anne Tyler for its wryness, humour and subtlety.

The Complete Works of Shakespeare because God knows when I’ll be rescued.

Some David Sedaris to lift my spirits.

Nuskha-e-Wafa by Faiz Ahmed Faiz so I can keep myself busy by learning all of his greatest ghazals and nazams by heart and stunning everyone with my brilliance when I finally get rescued.

How have you been spending your days indoors?

MM: Editing, writing, recording my podcast ‘Browned Off’ and watching tons of Netflix. And eating chocolate!

If you didn’t pick satire, what would be another narrative style that you might consider?

MM: I’d write funny romances and whodunnits.

Do you think social media can have a positive impact in a field like politics, or is that too positivist? In theory of course yes, it is possible, like anything else, but do you think the system and political structures create politicians and workers on ground level who could actually wield it as a constructive tool?

MM: Of course social media can have a positive impact. Many activists use it for just such a purpose: they speak truth to power and set the record straight. As with everything else, in using social media too there is a choice involved.

What would Ruby do if she were embroiled in today’s South Asian politics? Do you think she would play the system like a fiddle or is the current situation maybe a bit too much even for her?

MM: She would do exactly what she does in the novel: she’d start off believing she is doing good. But very soon, in order to prove her loyalty to her party, she’d find herself peddling misinformation and abusing anyone who disagreed with the party line. And she’d still believe she was doing good.

There is a general despondency that seems to have settled in amongst people, with the pandemic and the general world-politics vortex where something goes wrong every day. We find ourselves once again in an age of anxiety. Do you think satire has the potential to push society towards introspection at such a time? Or is it consumed more like page 3 entertainment because people are too tired?

The Impeccable Integrity of Ruby R

Moni Mohsin

MM: I don’t really know. I think for satire to act as a catalyst for reform, there has to be some consensus on morality – on what we deem to be right and what we believe to be wrong. But in today’s deeply divided world I’m not sure we have that agreement any longer, if we ever did. My own ambitions as a writer are more modest. I am pleased if I can make someone smile when they read my work or recognize something I’ve written as being truthful.

Power and age very easily sway younger, more impressionable people. It happens with Ruby as well, who listens to one speech by Saif Haq and completely discards her reservations about a figure like him. Was the affair between Saif and Ruby a conscious narrative choice from the very beginning, considering it echoes the #metoo movement very closely, or was it something that born later out of the sequence of narrative events?

MM: It is not just the young who fall prey to the false promises of the powerful and the privileged. The affair between Ruby and Saif, while it is an actual thing in the book, is also meant to function as a metaphor for how we the public, who should know better, allow ourselves to be seduced by celebrity and by the intoxicating but divisive rhetoric of populist leaders.

Saif is said to have been modelled on Imran Khan, although he is an echo of several public figures we have seen. Did you have any specific figure in mind when you wrote him or is he more of an amalgamation?

MM: In creating Saif Khan I channelled the arrogance, entitlement and charisma of several populist leaders who are prominent in the world today.

The heightened focus on integrity in a field that obviously seems to have none is a very striking anomaly through the novel. In India for example politics seems to have given up on pretences and external polish. Do you think perhaps that morally bankrupt politicians are more effective when they work with the façade of integrity, parading the importance of being earnest? Or is the scene changing in that regard?

MM: I don’t think that Indian leaders have dispensed with their soaring rhetoric about purifying their country and returning to some mythical golden age while simultaneously stepping into a glittering future. Populist leaders never tell their adoring public the truth: that they have no quick fixes and that meaningful change comes only through hard work and sacrifice. The best they can do when their hypocrisy or incompetence comes to light is to either blame others (the opposition, or minorities, or bad neighbours or hostile super powers or the ‘lying’ media or whatever) or else, conveniently ignoring the truth.

~

The Impeccable Integrity of Ruby R is an exciting satire on the life and times of our current politics.