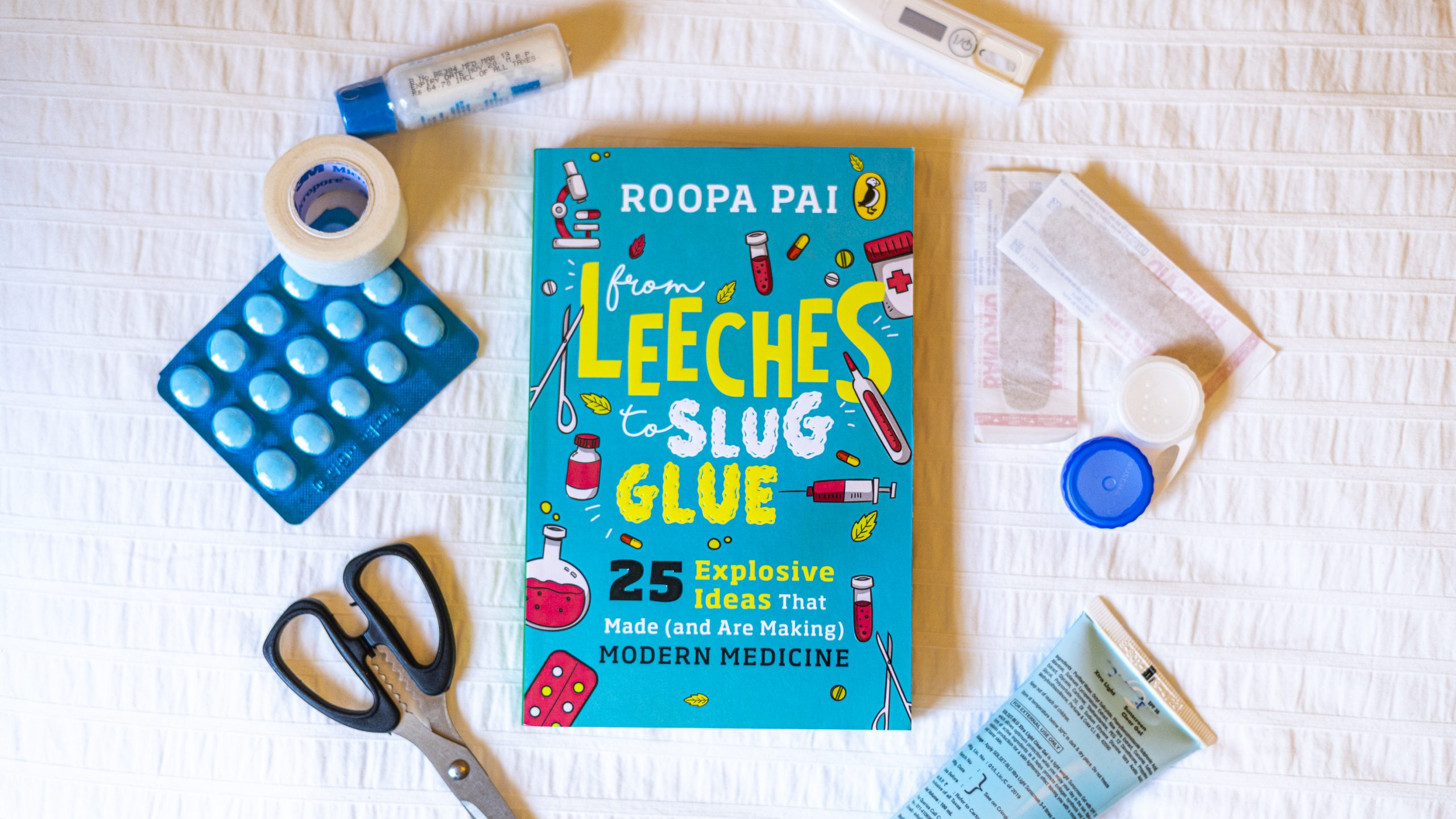

For centuries, mankind has marvelled at the intricacies of the human body. Mapping out the advances in medical science, Leeches to Slug Gluegoes back in time to help you and your children understand how we reached where we are today. This journey not only demonstrates the awe-inspiring range of human intelligence but also applauds the spirited quest for improvement and innovation. The great minds that relentlessly broadened the scope of science worked their way through many trials and failures which led to waves of change, often shattering beliefs and altering established theories.

Featuring groundbreaking ideas, trivia, factoids, and more, this book will make you question your notions of what makes a person ‘whole’. And it will fill you with wonder at the innovations, inventions and discoveries that have made-and are continuing to make-the young science of modern medicine.

Here are 6 myths that have been busted in From Leeches to Slug Glue to reveal the facts that helped medical science gain momentum.

Myth 1: Human beings are defenceless against diseases that evil spirits cast on them.

The holistic approach propounded by Ayurveda offered man a ray of hope to dispel the darkness that shrouded all maladies. Ayurveda – the science of life – empowered man with the ability to sync the human body with its natural rhythms to strengthen its immune system and keep diseases at bay.

Does this ‘Prevention is better than cure’ theory really work, though?

Well, it certainly makes for sound common sense! Roopa Pai writes ‘….there’s no reason why you shouldn’t take the core advice of Ayurveda for good health: eat right, poop regularly, sleep early, wake up at dawn, do some yoga in the early sunlight, pause several times a day to take deep and long breaths, be disciplined about exercise, spend some quiet reflective time with yourself each day and, yes, whenever you have the time, get a massage!’

*

Myth 2: The great physician Charaka single-handedly composed the 120-chapter long Charaka Samhita.

The nearly 2000-year-old Charaka Samhita is a seminal work that helped unravel the many mysteries of human physiology – namely the functions performed by various organs and matters related to digestion and reproduction.

Was it all the genius of one man, however? Maybe not.

Here’s what ‘Leeches’ has to say about it. ‘Some experts who have studied the text extensively believe there wasn’t one Charaka, but several (‘charaka’ is Sanskrit for wanderer). These charakas, they say, were scholars who had chosen to make the science of healing their specialty, and went from village to village using their extensive knowledge of pathology (the causes of disease), clinical examination, diagnosis and medicinal herbs and minerals to make sick people better.’

*

Myth 3: Hippocrates was the ‘Father of Medicine’, the first to create a formal system of diagnosis.

The Greek physician Hippocrates is believed to have composed the historically and medically significant Hippocratic Corpus. Well before Hippocrates came along in 460 BCE, however, the ancient Egyptians seem to have made inroads into understanding how to treat grievous injuries, even those involving the skull and spine, as demonstrated in an important Egyptian ‘medical papyrus’ translated by famous American Egyptologist James Henry Breasted in 1930.

This was the first clear evidence we had that the healing practices of the Egyptians were more than just chants and incantations, which makes the notion of Hippocrates as the earliest proponent of a formal system of medicine debatable.

‘The Edwin Smith Papyrus,’ writes Roopa Pai, ‘describes forty-eight cases of bodily injury—fractures, wounds, dislocations, tumours—starting from the head and going downwards from there, and includes information, in each case, about how the patient is to be examined, what the likely diagnosis is and a calculated guess as to whether the injury will heal and the patient will survive (this is called prognosis).’

You go, ancient Egyptians!

*

Myth 4: The ten numerals, and their symbolic representations – 0, 1, 2… 8, 9 – were the brainwave of the Arabs.

Under the patronage of the Gupta kings, who ruled north and central India between the 3rd and 6th centuries, the great INDIAN mathematician Bhaskara first wrote numbers as figures—1 to 9—and created what was then called the Hindu decimal system. Bhaskara was also the first to represent zero as a circle.

Why did the term ‘Hindu numerals’ not gain popularity, then?

‘Although the Arabs themselves always referred to the ten numerals as Hindu numerals (Hindu was a word the Persians used for the people of the land beyond the Indus river),’ explains the book, ‘Europeans, who were introduced to them by the Arabs around the ninth century, wrongly referred to them as Arabic numerals, and the name stuck.’

Now you know.

*

Myth 5- Surgeons have always occupied the highest rung of the medical ladder

In the present medical scenario, surgeons are revered as the physical embodiment of the leaps that the science has taken over the centuries. But it wasn’t always the case. In fact, in Europe of the Middle Ages, it was lowly ‘barber surgeons’ – barbers who otherwise shaved people and cut their hair – who conducted all surgeries.

Here are more details. ‘In those days, dissections in medical colleges were done by barber surgeons according to the instructions of the professor, while the students gathered around and watched. Physicians—the ones who went to college and learned to treat disease—considered themselves far too posh for something like dissection or surgery; that was the job of the unlettered barber….’.

Well, thank the Lord they didn’t think to use butcher-surgeons, right?!

*

Myth 6: Full moon nights triggered ‘madness’ in people.

In his Treatise on Insanity, Philippe Pinel campaigned for the moral and compassionate treatment of mentally ill people, thereby laying the foundation for the discipline called psychiatry.

Could he rupture the notion of ‘insanity’ being a result of ‘demonic possession’? It was not easy, but in the end, Pinel succeeded through dint of sheer force of will, a strong moral compass, and tons of patience.

‘He closely observed, documented and named a number of different mental disorders, spending hours talking with patients, in keeping with his belief that while the sufferer may seem irrational or delusional in certain ways, they had seldom ‘lost all sense of reason’, and could therefore, often, be ‘talked out’ of their problems. Pinel also insisted that not every kind of mental illness was permanent—some were temporary, result of stressful events in the person’s life, and not the result, as was commonly believed, of cosmic events like, say, the phases of the moon.’

Yes, phases of the moon! Where do you think the ‘luna’ in ‘lunatic’ comes from?

To discover dozens of ‘No way!’ nuggets like these in this fun, info-packed romp through 2500 years of human health and healing, read From Leeches to Slug Glue!