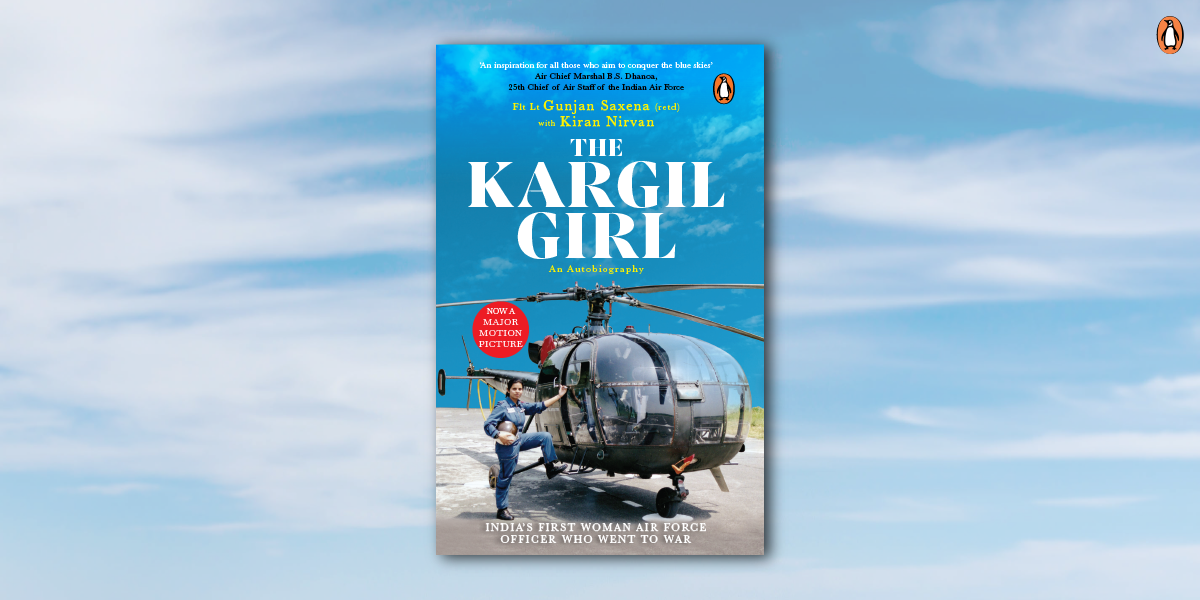

1994, twenty-year-old Gunjan Saxena boards a train to Mysore to appear for the selection process of the fourth Short Service Commission (for women) pilot course. Seventy-four weeks of back-breaking training later, she passes out of the Air Force Academy in Dundigal as Pilot Officer Gunjan Saxena.

On 3 May 1999, as the Kargil war begins, the time comes for Saxena to prove her mettle. From airdropping vital supplies to Indian troops in the Dras and Batalik regions and casualty evacuation from the midst of the ongoing battle, to meticulously informing her seniors of enemy positions and even narrowly escaping a Pakistani rocket missile during one of her sorties, Saxena fearlessly discharges her duties, earning herself the moniker ‘The Kargil Girl’.

The Kargil Girl

Gunjan Saxena, Kiran Nirvan

This is her inspiring story, in her words. Read on for some fascinating insights into the meticulous training and strategic testing that goes into the making of an officer of the Indian Defence Forces.

Testing involves almost superhuman levels of co-ordination and dexterity

‘Using one’s peripheral vision, one had to press the buttons on an adjacent panel as they lit up. A red and green light on the screen had to be switched off using one’s left hand. All this had to be done quickly and simultaneously.’

The psychological tests to determine the mental strength of people who will lead in battle form a major chunk of the SSB exam—the Word Association Test (WAT), the Thematic Appreciation Test (TAT), the Self-Description (SD) test and the Situation Reaction Test (SRT).

‘These might just sound like acronyms to many, but for defence aspirants, these are the devils that stand at the gates of any SSB centre, ready to peek into the darkest corners of their minds and reveal their true, hidden selves.’

There is almost no margin for error in even a single applicant-as the strength of the chain is only as much as that of the weakest link.

‘The rate of error has to be zero—one wrong selection and an entire platoon, battalion or even a division may suffer. Someone can be denied for being too young, too old, for having flat feet, anxiety, phobias and so on.’

There are several levels of testing and training that must be passed before one becomes a commissioned army officer

‘Getting recommended was only the beginning. The path to glory was strewn with obstacles, ones that would almost break me.’

Training commences with ordeals designed to engender the highest levels of fitness

‘Introductions began with us—the first-termers—in high-plank position. Some of us couldn’t even remain in the position for thirty seconds. Whenever one of us fell flat on the floor, the others were asked by the seniors to do more push-ups.’

A lack of preparation is simply not an option in the Indian military.

‘I spent the night thinking about what had gone wrong. I knew the answer, but I was not quite ready to accept it—not until the next day, when I finally told the CFI that it was the result of my lack of preparation. A long lecture followed, a lecture that shook me nice and proper, and I decided to pull up my socks after the incident.’

Every possible emergency is thrown at one out of the blue to test your ability to handle difficult situations instantly.

‘In the absence of rudders, which control the nose of the helicopter, it becomes difficult to balance the flight. I had never imagined Group Captain Sapre would ask me to perform this emergency procedure.’

The intense course culminates in a passing out parade that requires even greater levels of rigorous preparation!

‘Exhausted from the morning parade practice, we would hardly be left with any energy to go for it again in the afternoons. The scorching heat of peak summer, mixed with the heat reflected from a metalled parade ground, would leave us drenched in sweat.’

And despite all of this-the brave cadets who undergo this have no regrets in doing their duty.

‘Indian military is one place that is free from any gender bias or discrimination. If I could spend the rest of my life in uniform serving in the armed forces, I would willingly do so.’