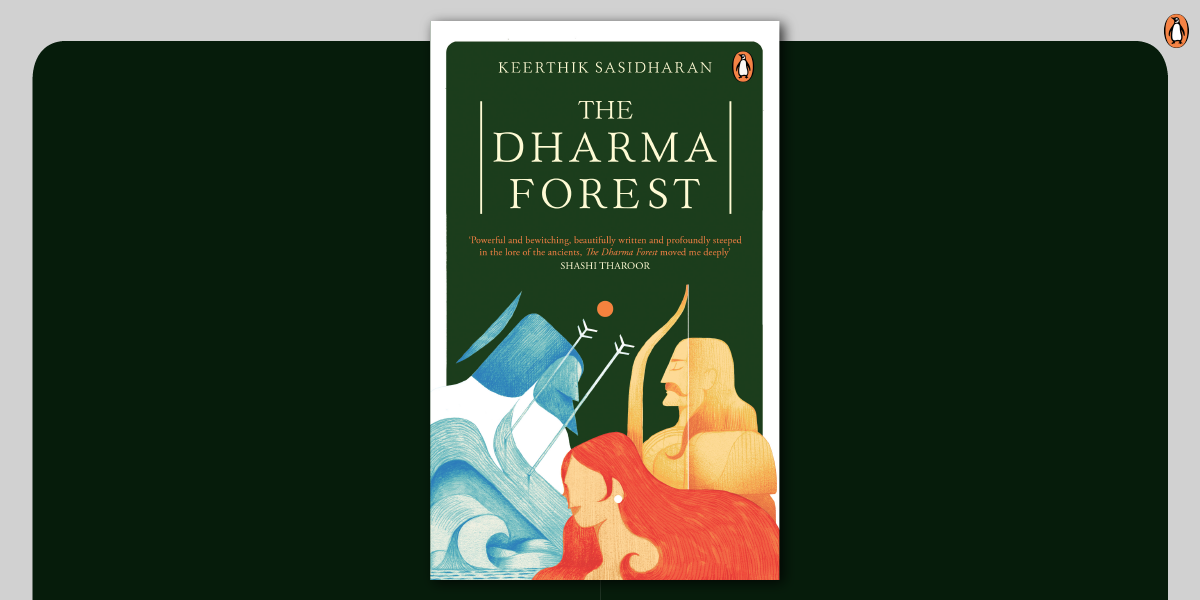

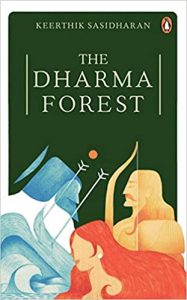

As the Mahabharata war wages on, it shows no mercy and takes no prisoners. Death and destruction abound.

In the midst of a world rendered unrecognizable by the lust for power, malice and the machinations of war stand Bhishma, contemplating the immeasurable death he sees around himself as a man who cannot die, Draupadi, above and beyond the chaos and yet at the very centre of it, trying to protect her husbands at any cost, wondering whom to trust, and Arjuna, beloved, conflicted and melancholic in equal measure, uncertain of the ultimate cost of the war he is intent on winning. The Dharma Forest is a magnificent first novel in a trilogy filled with complex characters, conflicted loyalties and erotic jealousies from India’s most beloved epic.

Here’s an intriguing excerpt from the book.

**

By the time the arrowhead left the bow’s frontal arch, Jara was already filled with regret. He could have been more patient; he could have not abandoned his aspiration for non-violence; he could have not surrendered to who he truly was—one who loved to hunt and kill. All the while as the arrow travelled, Jara noticed that the trees had stopped swaying and the winds ceased their frenzied moves. Every falling twig was now audible, each drop of dew hit the grounds with a crackle. Up from the trees, the leaves began to abandon their tenuous bonds with the branches, frogs scampered around their puddles nervously and birds in the skies circled anxiously, like expectant fathers at the hour of birth. The forest stilled itself in anticipation. And the evening sky had acquired a darkness that Jara had rarely seen. The world was now brimming over with portents that not even the darkest oracles could fathom. And then, all too suddenly, he heard the arrow land with a thud and tear into some flesh which, ironically, brought about a semblance of normalcy to that moment thanks to the iron laws of cause and effect which had now seemingly prevailed. His arrow, as always, had found its mark, and Jara sighed in relief—finally!—as if some long nursed revenge had eventually found its release. From afar, he could see a pool of blood begin to flow and wet the grounds, and a voice in his head told him that an hour of sacrament was near.

Jara ran towards his mark, past the small ponds and the trees, to inspect the animal that lay there. Even as he hurried, he prayed that he may find an injured deer and not a dead one. To assuage his guilt, he told himself that he would bandage the animal and let it go. The flute’s melancholic song, meanwhile, had come to a stop. From the skies a roar broke out and boomed through the trees and branches, which had already shed their leaves, as if an untimely winter had arrived. Jara found himself running through a corridor of yellow and green when he heard the forests echo three times.

Jayaa, Jayaa, Jayaa…

Before he could make sense of it all, he had arrived at a spot where blood seeped freely into the earth. And there he found a man with many arms—was this a God who had lost his way, Jara asked himself in wonder and fear; his complexion was as dark as the blue nights of Jara’s dreams, and from his feet, blood trickled steadily. Jara’s arrow had sliced away the ankle of his foot. Instead of pain and horror, however, this injured otherworldly person sat there in silence, with his eyes closed, as if he was meditating. And then, perhaps stirred by Jara’s presence, he opened his eyes and smiled at him. A generous and beatific smile that took Jara by surprise, for he had expected to be on the receiving end of anger and abuse. Overwhelmed by grief and guilt on having hurt somebody, Jara bowed to this injured being and for reasons unknown to him, tears welled up in his eyes. He bent down to touch this being’s feet, out of concern and in regret, as if to make amends for this gratuitous injury. When Jara looked up again, the many arms on his body were no longer there. He was just another ordinary man, even though his presence exuded a form of gentleness and beauty of the kind that Jara had never thought possible in another human. Perhaps, Jara tried to reason, it was another trick played by the forest. Then, this kindly one spoke, ‘Jara, my dear friend. I hope it wasn’t too difficult for you to find me.’

Jara looked at him again, only to recognize an intuition froth within him that his wanderings through the forest which had lasted for weeks, had now come to an end. The man’s presence—despite the blood and agony all around—filled Jara with a kind of peace that he had not experienced in a long while. Then, even as he bled to death, the man said with an easy contentment: ‘I am Devaki’s son, Rukmini’s husband, and Arjuna’s friend. I am also known as Krishna of the Yadavas.’

He paused to let silence enter between them and then said to Jara, ‘I have waited for you my whole life.’

**