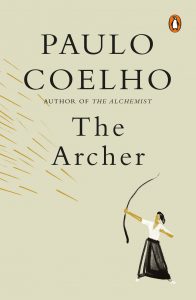

Anyone who reads Paulo Coelho is changed in some fundamental way. The power of his words is rare, and the breadth of his scope is not easily matched. Here is an excerpt from his newest book The Archer, exploring truths of life through an impactful metaphor:

~

‘Tetsuya.’

The boy looked at the stranger, startled.

‘No one in this city has ever seen Tetsuya holding a bow,’ he replied. ‘Everyone here knows him as a carpenter.’

…Tetsuya made as if to resume his work: he was just putting the legs on a table.

‘A man who served as an example for a whole generation cannot just disappear as you did,’ the stranger went on. ‘I followed your teachings, I tried to respect the way of the bow, and I deserve to have you watch me shoot. If you do this, I will go away and I will never tell anyone where to find the greatest of all masters.’

The stranger drew from his bag a long bow made from varnished bamboo, with the grip slightly below center. He bowed to Tetsuya, went out into the garden, and bowed again toward a particular place. Then he took out an arrow fletched with eagle feathers, stood with his legs firmly planted on the ground, so as to have a solid base for shooting, and with one hand brought the bow in front of his face, while with the other he positioned the arrow.

The boy watched with a mixture of glee and amazement. Tetsuya had now stopped working and was observing the stranger with some curiosity.

With the arrow fixed to the bowstring, the stranger raised the bow so that it was level with the middle of his chest. He lifted it above his head and, as he slowly lowered his hands again, began to draw the string back. By the time the arrow was level with his face, the bow was fully drawn. For a moment that seemed to last an eternity, archer and bow remained utterly still. The boy was looking at the place where the arrow was pointing, but could see nothing. Suddenly, the hand on the string opened, the hand was pushed backward, the bow in the other hand described a graceful arc, and the arrow disappeared from view only to reappear in the distance.

‘Go and fetch it,’ said Tetsuya.

The boy returned with the arrow: it had pierced a cherry, which he found on the ground, forty meters away.

Tetsuya bowed to the archer, went to a corner of his workshop, and picked up what looked like a slender piece of wood, delicately curved, wrapped in a long strip of leather. He slowly unwound the leather and revealed a bow similar to the stranger’s, except that it appeared to have seen far more use.

‘I have no arrows, so I’ll need to use one of yours. I will do as you ask, but you will have to keep the promise you made, never to reveal the name of the village where I live. If anyone asks you about me, say that you went to the ends of the earth trying to find me and eventually learned that I had been bitten by a snake and had died two days later.’

The stranger nodded and offered him one of his arrows.

Resting one end of the long bamboo bow against the wall and pressing down hard, Tetsuya strung the bow. Then, without a word, he set off toward the mountains.

The stranger and the boy went with him. They walked for an hour, until they reached a large crevice between two rocks through which flowed a rushing river, which could be crossed only by means of a fraying rope bridge almost on the point of collapse.

Quite calmly, Tetsuya walked to the middle of the bridge, which swayed ominously; he bowed to some- thing on the other side, loaded the bow just as the stranger had done, lifted it up, brought it back level with his chest, and fired.

The boy and the stranger saw that a ripe peach, about twenty meters away, had been pierced by the arrow.

‘You pierced a cherry, I pierced a peach,’ said Tetsuya, returning to the safety of the bank. ‘The cherry is smaller. You hit your target from a distance of forty meters, mine was half that. You should, therefore, be able to repeat what I have just done. Stand there in the middle of the bridge and do as I did.’

Terrified, the stranger made his way to the middle of the dilapidated bridge, transfixed by the sheer drop below his feet. He performed the same ritual gestures and shot at the peach tree, but the arrow sailed past.

When he returned to the bank, he was deathly pale.

‘You have skill, dignity, and posture,’ said Tetsuya. ‘You have a good grasp of technique and you have mastered the bow, but you have not mastered your mind. You know how to shoot when all the circumstances are favorable, but if you are on dangerous ground, you cannot hit the target. The archer cannot always choose the battlefield, so start your training again and be prepared for unfavorable situations. Continue in the way of the bow, for it is a whole life’s journey, but remember that a good, accurate shot is very different from one made with peace in your soul.’

The stranger made another deep bow, replaced his bow and his arrows in the long bag he carried over his shoulder, and left.

~

We can’t wait to settle in with The Archer this winter.