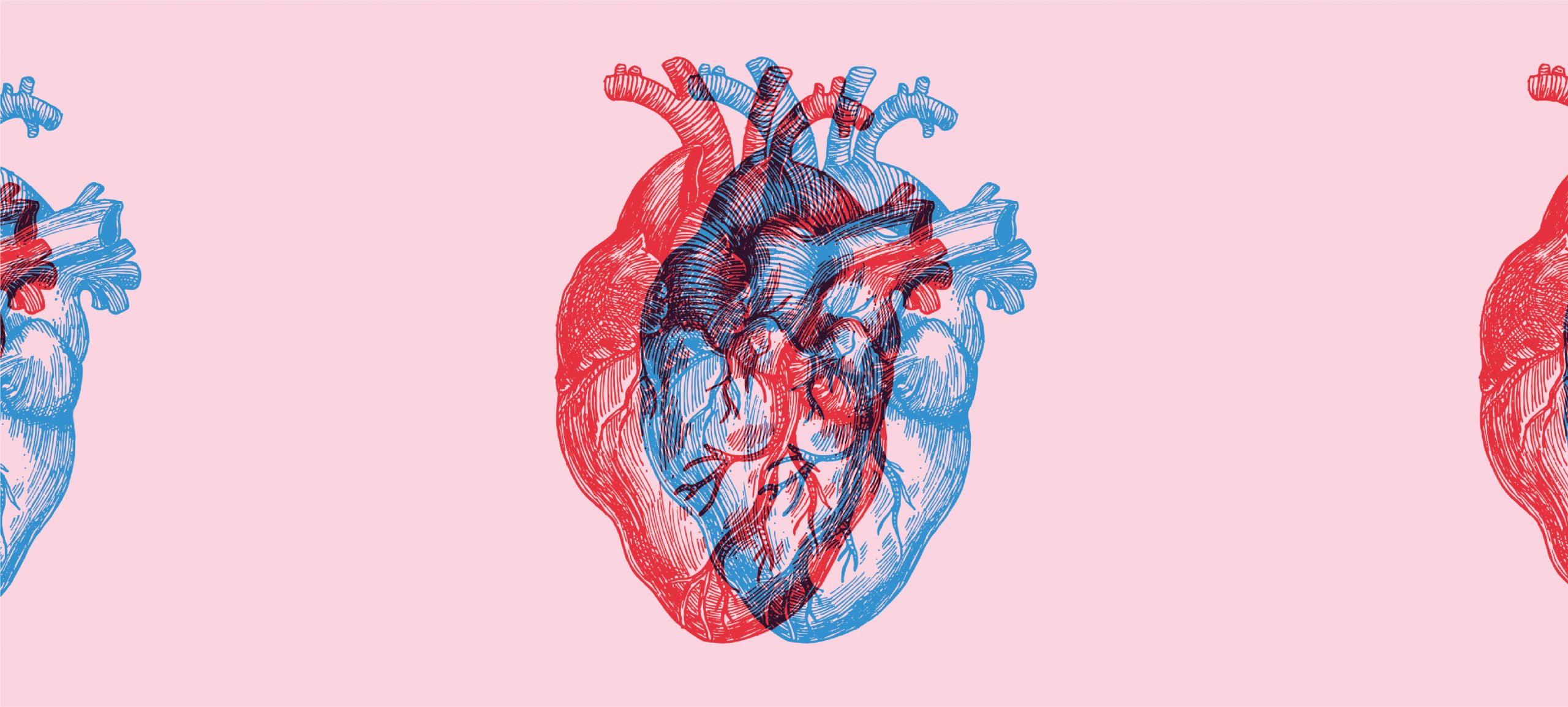

Sandeep Jauhar’s brilliant Heart: A History blends historical events with evocative glimpses into his own experiences as a cardiac surgeon. Befittingly, for an organ that has been considered the ‘driver of emotion and the seat of the soul’, the book pulses with emotion-from that of the path-breaking surgeons who dedicated their lives to making sure the hearts continued to beat, experimenting on themselves in the absence of facilities and the patients who willingly submitted to experimental and uncertain treatments; to his own emotions, uncertainties and fears that powered him through a gruelling medical career, Sandeep Jauhar puts his heart into the history of the organ considered most significant in our collective imaginations.

Read on for seven personal experiences of Sandeep Jauhar-straight from the heart

His deep-seated fear of the heart as the executioner of men in the prime of their lives

“‘It was a heart attack,’ the doctor said, dispelling the family’s belief that a snake had killed their elder. My grandfather had succumbed to the most common cause of death throughout the world, sudden cardiac death after a myocardial infarction, or heart attack, perhaps triggered in his case by fright over the snakebite.”

His first dissection of a frog. (He launched on a successful medical career despite the this rather traumatic experience!)

“The electrode tips were way too big, nearly the size of the heart itself. Nevertheless, in a panic, I directed them at the pea- sized organ, forgetting that they were still hooked up to the battery. When they made contact, an electrical spark crackled, singeing the chest. It smelled awful, even worse than the formaldehyde soaked specimens in Mr. Crandall’s storage locker. By the time my mother came outside, I was bawling. I had tortured the poor creature, and moreover had nothing to show for it.”

An emotional connect with the first cadaver he dissected

“Even from our first encounter, my cadaver confounded me. He was South Asian. In the culture I grew up in, people rarely donate their bodies to science; they belong to their loved ones. In his final decision— just before death—my cadaver likely defied the wishes of his family, his children, maybe even his wife. Why? I wondered. Of course, I would never know, but nonetheless I felt a sort of kinship to the body before me. The cadavers, our professor said, might remind us of a person we once knew— a close friend or relative who had passed away. Or perhaps a grandfather who lived only in stale stories.”

The painful loss of a patient despite the grueling hours and work a doctor puts into attempting to save their lives

“Shah never called me to tell me what happened, but the next day I heard from my parents that the patient never made it out of the OR. His blood pressure continued to drop, despite the balloon pump and intravenous medications, and around seven that morning, nearly seven hours after we’d arrived at the hospital, he died, another victim of endocarditis, Osler’s great killer. It was an important lesson for me at that early stage in my career. No matter the extraordinary progress that has been made in heart surgery over the past century, the heart remains a vulnerable organ. Despite our best efforts, cardiac patients still die.”

When fear is both teacher and inspiration

“What motivated the long hours was fear: fear of overlooking something that could hurt a patient, of course, but more immediately fear of rebuke, of being dressed down for mismanagement or an oversight. And so I came to think of my cardiology training as being on dual tracks: learning about the heart, obviously, but also what was in my heart— what I was made of—at the same time.”

The shock of the doctor being put in the same position as the patient

“After Dr. Trost reviewed the images, she called me into the reading room. The gray- and- white pictures were up on a large monitor. White specks, radiographic grit, were in all three of my coronary vessels. The main artery feeding my heart had a 30 to 50 percent obstruction near the opening and a 50 percent blockage in the midportion. There was minor plaque in the other

two arteries, too. Sitting numbly in that dark room, I felt as if I were getting a glimpse of how I was probably going to die.”

…..and moving past a difficult diagnosis

“As another summer winds down, my CT scan is a distant memory. It was supposed to change everything, but in the end it was a hiccup, a PVC, and my life has returned to its normal rhythm. Like when you plan a trip somewhere and you think the place will feel different, the way you see it in pictures, and then you get there and it’s the same as the place you came from: same sky, same air, same clouds. Of course, I’ve made changes. I exercise almost every day now, and I eat better, too. I spend more time with my children and with friends. I still enjoy working hard, but I am no longer so contemptuous of relaxation.”

Affecting, engaging, and beautifully written, Heart: A History takes the full measure of the only organ that can move itself.