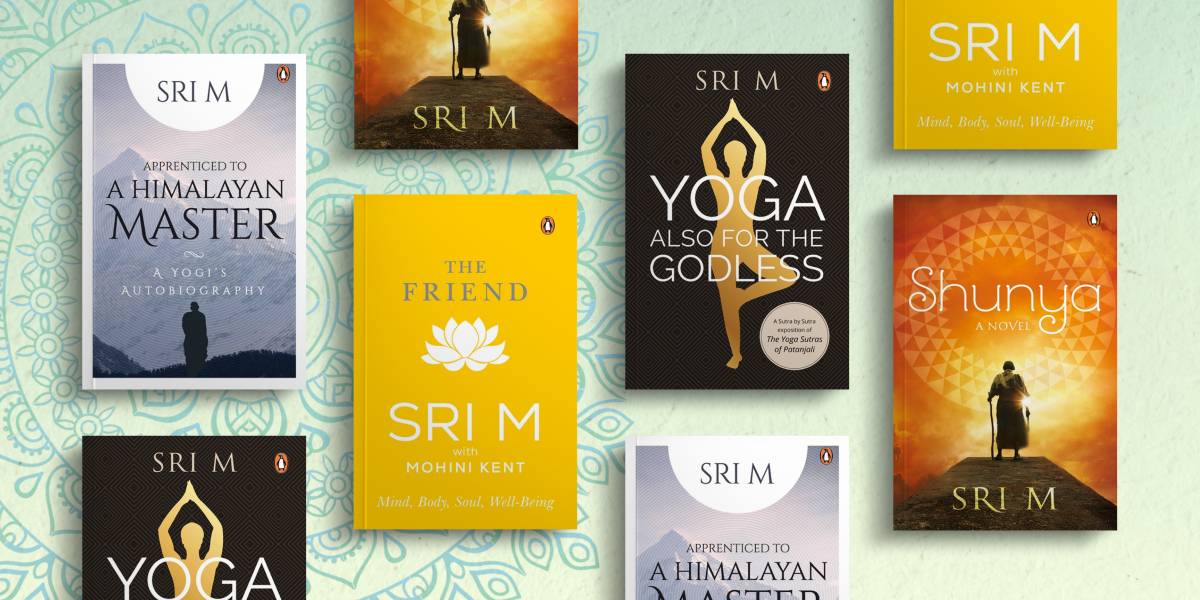

The spiritual awakening of Sri M and his journey into a yogi’s life has inspired people worldwide. Rather than focusing on a singular concept, Sri M and his foundation, Satsang Foundation, believe in generosity, faith and helping spiritual seekers no matter where they have come from.

The following are glimpses of his extensive bibliography, starting from Apprenticed To A Himalayan Master to Yoga Also For The Godless. His latest book The Friend is written in the guru-disciple style of conversation with Mohini Kent.

*

Apprenticed To A Himalayan Master

Both my sister and I went to the Holy Angels’ Convent, which was walking distance from home. As soon as we came back from school, it was our usual practice to wash up, eat something light, and play in the backyard till sunset. At sunset, we were supposed to wash our faces, hands and feet and sit for a short Arabic and Urdu prayer with our grandmother. After that, we would finish our school homework and have dinner. Sometimes my grandmother would tell a ew stories from the Arabian Nights, or her own experiences, and then off to bed.

That particular day, my sister who was more studious than me (no wonder that she became a senior Indian Administrative Services Officer), cut short her playtime and went back into the house earlier than usual. I was wandering around the courtyard doing nothing in particular. Dusk was not far from setting in. The light had mellowed to a soft golden yellow. I thought I would go home too and perhaps find some snacks in the kitchen. So I turned towards the house. However, for reasons I cannot explain to this day, I turned instead and walked towards the jackfruit tree at the far end of the courtyard. There was someone standing under the tree and was gesturing for me to come forward.

The normal instinct would have been to bolt, but instead I was surprised to find I felt no fear whatsoever. A strange eagerness to go closer to the stranger filled my heart. I quickened my steps and was soon standing in front of him. Now I could see clearly. The stranger was tall, extremely fair and his well-built muscular body was bare except for a piece of white cloth that was wrapped around his waist and reached just above his knees. He was also barefoot.

I was intrigued by this strange man who had slightly brown and thickly matted long hair gathered over his head in a big knot that looked like a tall hat. He wore large, brown, probably copper earrings and carried a black, polished water pot in his right hand. By far, the most striking of his features were his eyes: large, brownish black, glittering and overflowing with love and affection. He put his right hand on my head without any hesitation and his kind voice said in Hindi, ‘Kuch yaad aaya,’ which means, ‘Do you remember anything?’

I understood the stranger’s words perfectly, for although our family had settled in Kerala for generations, we spoke a peculiar dialect of Urdu known as Dakkhini, very similar to Hindi. ‘Nai,’ no, I said.

He then removed his hand from my head and stroked the middle of my chest with it, saying, ‘Baad mein maalum ho jaayega. Ab vapas ghar jao.’ (You will understand later. Go home now.) I still did not understand what he was trying to convey, but instantly obeyed the command to go back home. As I hurried back, I felt as if his touch had made my heart lighter. Reaching the last step to the rear entrance of the house, I turned around to have a last glimpse of the stranger under the jackfruit tree, but he was gone. There was no one there.

*

Shunya

For well over sixteen years, Sadasivan had to pass the old, abandoned cremation ground at midnight on his way back home from his toddy shop.

He prided himself on the fact that he didn’t believe in ghosts and ghouls and other superstitions and yet, every time he passed the gate of the crematorium, an unknown fear gripped him and his hair stood on end.

That night, too, as he whizzed past the gate on his Royal Enfield motorbike—an upgrade from his old bicycle which he had felt took ages to clear the distance—Sadasivan followed the simple rule he had devised to make things easier: ‘Don’t look in the direction of the crematorium. Go as fast as you can.’

He had almost passed its gate when he distinctly heard a voice calling him out by name. Try as he might, he couldn’t resist the temptation to turn and look. A shiver went up his spine.

A figure clad in white leapt out of the gate and, in the bright light of the solitary street lamp, Sadasivan could see him coming in his direction.

He lost control of his motorbike which hit a protruding flagstone, skid sideways, and sent him flying across the road.

As he picked himself up, he was scared stiff to see the white-robed figure right by his side.

‘Umph! Not bad. No major damage, Sadasiva. Get up and go home. Don’t be frightened. I am not a ghost, ha ha!’

Sadasivan got up, dusted his clothes and picked up the motorbike which had fallen a few metres away. The bike seemed fine except for a dent or two and one broken rearview mirror. Then he noticed that the skin on both his elbows and his left knee had peeled off. No other damage.

The stranger followed him to the bike.

‘Who the hell are you,’ shouted Sadasivan, angrily, ‘popping up from the cremation ground at midnight like a ghost? Haven’t seen you in these parts and how do you know my name?’

‘Sadasiva, I’ll see you tomorrow at your toddy shop, okay? We’ll talk then. Now go home and take care of yourself. There are no ghosts—go home.’

Sadasivan started his bike and rode home wondering who this crazy man was. He had seen him at close quarters: a single piece of unwashed white mundu was wrapped around his waist with an equally unwashed, loose cotton shirt; he was barefooted and fair-complexioned, with a pointed Ho Chi Minh beard. Who was he? Didn’t Sadasivan notice a bamboo flute in his hand? Where did he spring from? He was certainly not a local and yet he spoke Malayalam. By the time he reached his house his anger had vanished and, for some strange reason, he was looking forward to seeing the stranger the next day.

*

Yoga Also For The Godless

Some years ago, I met a smart young lady who said to me, ‘M, I believe you are a yogi. I think you might be able to shed light on a question on yoga. I was very keen on practising yoga after I heard about its health benefits. The fact that many celebrities practise yoga to keep in shape also influenced me.

‘I approached a yoga teacher. He started teaching me Sanskrit shlokas in praise of God and insisted that I chant them. I tried convincing him that I was an atheist. I was born a Hindu but do not think it necessary to believe in God. He strongly felt that without invoking Lord Ganesha, I could not begin my yoga practice and insisted that the aim of yoga was God-realisation.

‘I told him that there is no God and, therefore, learning yoga for me was not to reach something that, according to me, did not exist. He was adamant and asked me to find another instructor’.

‘What do you think?’

This yoga teacher, the girl referred to, is not an exception. Thousands of people labour under the mistaken notion that yoga is a theistic philosophy and is not for atheists and agnostics. Some yoga teachers admit that mere postures can provide health benefits, but the higher aspects such as the expansion of consciousness and the attainment of Kaivalya, freeing the consciousness from the limitations of conditioned thinking and awakening to its infinite potential, is not realisable by the godless.

This book is meant precisely to change such misunderstood notions about yoga, while serving as a practical guide to practise yoga to perfection, without the ‘God crutch’. You will understand that ancient yoga philosophy has almost no interest in the concept of a creator or an all-powerful God, who controls you and throws you into heaven or hell according to his whims and fancies.

Even the great Patanjali, considered the foremost and earliest exponent of systematic yoga, in his masterpiece, The Yoga Sutras, uses Ishwara (God) only twice in the entire text and only as a useful adjunct to the main practices. Whether Patanjali’s Ishwara denotes an omnipotent ‘thundering God’ or the tranquil Purusha of Sankhya philosophy is an age-old question that needs a healthy debate. We will look into these and other points of view because to practise yoga well, an understanding of its philosophical roots is important.

Lastly, this book is an attempt to save the purity of yoga from being adulterated by religious cults and politico-religious outfits keen to exploit the masses and use them to their advantage.

*

Get your own Sri M collection from the nearest bookstore or visit Amazon.