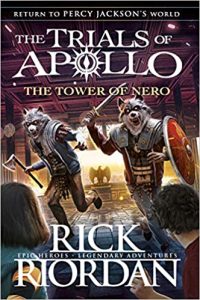

The battle for Camp Jupiter is over. New Rome is safe. Tarquin and his army of the undead have been defeated. Somehow Apollo has made it out alive, with a little bit of help from the Hunters of Artemis.

But though the battle may have been won, the war is far from over.

Now Apollo and Meg must get ready for the final – and, let’s face it, probably fatal – adventure. They must face the last emperor, the terrifying Nero, and destroy him once and for all.

Here’s a glimpse into the action-packed world of The Tower of Nero, the final novel in The Trials of Apollo series.

**

WHEN TRAVELLING THROUGH WASHINGTON, DC, one expects to see a few snakes in human clothing. Still, I was concerned when a two-headed boa constrictor boarded our train at Union Station.

The creature had threaded himself through a blue silk business suit, looping his body into the sleeves and trouser legs to approximate human limbs. Two heads protruded from the collar of his shirt like twin periscopes. He moved with remarkable grace for what was basically an oversize balloon animal, taking a seat at the opposite end of the coach, facing our direction.

The other passengers ignored him. No doubt the Mist warped their perceptions, making them see just another commuter. The snake made no threatening moves. He didn’t even glance at us. For all I knew, he was simply a working-stiff monster on his way home.

And yet I could not assume . . .

I whispered to Meg, ‘I don’t want to alarm you –’ ‘Shh,’ she said.

Meg took the quiet-car rules seriously. Since we’d boarded, most of the noise in the coach had consisted of Meg shushing me every time I spoke, sneezed or cleared my throat.

‘But there’s a monster,’ I persisted.

She looked up from her complimentary Amtrak magazine, raising an eyebrow above her rhinestone-studded cat-eye glasses. Where?

I chin-pointed towards the creature. As our train pulled away from the station, his left head stared absently out of the window. His right head flicked its forked tongue into a bottle of water held in the loop that passed for his hand.

‘It’s an amphisbaena,’ I whispered, then added helpfully, ‘a snake with a head at each end.’

Meg frowned, then shrugged, which I took to mean Looks peaceful enough. Then she went back to reading.

I suppressed the urge to argue. Mostly because I didn’t want to be shushed again.

I couldn’t blame Meg for wanting a quiet ride. In the past week, we had battled our way through a pack of wild centaurs in Kansas, faced an angry famine spirit at the World’s Largest Fork in Springfield, Missouri (I did not get a selfie), and outrun a pair of blue Kentucky drakons that had chased us several times around Churchill Downs. After all that, a two-headed snake in a suit was perhaps not cause for alarm. Certainly, he wasn’t bothering us at the moment.

I tried to relax.

Meg buried her face in her magazine, enraptured by an article on urban gardening. My young companion had grown taller in the months that I’d known her, but she was still compact enough to prop her red high-tops comfortably on the seatback in front of her. Comfortable for her, I mean, not for me or the other passengers. Meg hadn’t changed her shoes since our run around the racetrack, and they looked and smelled like the back end of a horse.

At least she had traded her tattered green dress for Dollar General jeans and a green VNICORNES IMPERANT! T-shirt she’d bought at the Camp Jupiter gift shop. With her pageboy haircut beginning to grow out and an angry red zit erupting on her chin, she no longer looked like a kinder-gartener. She looked almost her age: a sixth-grader entering the circle of hell known as puberty.

I had not shared this observation with Meg. For one thing, I had my own acne to worry about. For another thing, as my master, Meg could literally order me to jump out of the window and I would be forced to obey.

The train rolled through the suburbs of Washington. The late-afternoon sun flickered between the buildings like the lamp of an old movie projector. It was a wonderful time of day, when a sun god should be wrapping up his work, heading to the old stables to park his chariot, then kicking back at his palace with a goblet of nectar, a few dozen adoring nymphs and a new season of The Real Goddesses of Olympus to binge-watch.

Not for me, though. I got a creaking seat on an Amtrak train and hours to binge-watch Meg’s stinky shoes.

At the opposite end of the car, the amphisbaena still made no threatening moves . . . unless one considered drinking water from a non-reusable bottle an act of aggression.

Why, then, were my neck hairs tingling?

I couldn’t regulate my breathing. I felt trapped in my window seat.

**