In 1977, two staff reporters at the Patriot – John Dayal and Ajoy Bose – both in their twenties, occupied highly advantageous positions during the nineteen months of the Emergency to observe the turmoil wrought in the capital city of Delhi. In their book, For Reasons of State, they have supplied first-hand evidence of the ruthlessness with which people’s homes were torn down and the impossible resettlement schemes introduced.

The nation found itself in a whirlwind of fear, confusion, violence and destabilization, stemming from forced sterilizations, heartless evictions in the thousands, and the cruel imprisonment of many.

Here is an excerpt from the introduction of their book.

——————————————————————————————————————————————————–

The trouble with the post-election situation in India in 1977 is that the tiny bushes in the foreground have hidden the forest behind. Also hidden, from the less probing eyes, are the myriad beasts that had prowled the jungle so menacingly for twenty months and may well be there still, albeit in an enforced hibernation, hoping for more suitable climes before they flex their muscles again. After the Emergency was relaxed just before the elections to the Lok Sabha, information had trickled down about cases of police brutality in Delhi and the states.

After the new Janata Party government was formed at the Centre, a large volume of reports has appeared on corruption, specially favours shown with or without political duress to companies associated with Sanjay Gandhi and his friends. The Maruti scandal has been hogging newspaper headlines and public discussions and, for the time being, till perhaps the various commissions start their proceedings, even the reports of excesses during the Emergency have tended to take a back seat.

Formidable as it is, Maruti is not the final personification, nor even the most characteristic symbol, of despotic rule under the Emergency. At best it betrays only the logical extension of the happenings that had taken place and in which the principals had acted by the rule of the bazaar to make cash capital out of the political and administrative situation they had so successfully managed to create. This has been brought about by the total depoliticization of society and by the perversion of the administrative system which had indeed for quite some time before the Emergency become ripe for being taken over by upstarts.

Officials and politicians of even the petty variety are explaining their activities during the Emergency as being born out of fear. But it is worth remembering that fear was only one, and in fact for the senior officers and politicians, almost the least important, of the factors responsible for the situation. Those who have closely watched the administrative process of the Union Territory of Delhi just before, during, and after the months of Emergency would know that the diabolical plan was not just a case of Sanjay Gandhi or his friends creating people who would do their bidding. It was a case of such people existing within the administration, simultaneously finding an extra-constitutional centre of authority and recognizing in it the powerhead that would help them in their own respective ambitions. The ambitions of the politician, the official and the bosses of the youth wing of the ruling party had become coterminous, so identical as to be indistinguishable from one another.

At a general level, it now is easy to see the strategy that had been adopted to utilize the situation. In the political institution of the Delhi Pradesh Congress Committee (DPCC), the Congress-run Delhi Administration controlled eventually by a nominated lieutenant governor, the superseded municipal corporation run by an official of the DDA, the Delhi State Industrial Development Corporation (DSIDC) for industries, the New Delhi Municipal Council (NDMC), the subordinate electricity producer and distributor Delhi Electricity Supply Undertaking (DESU), Delhi University (DU) and in Delhi Police which is controlled simultaneously by the lieutenant governor and the central government, there had existed a situation just before the Emergency which had created a coterie of officials bent on consolidating individual power. Internal rivalries and power grouping had reduced most of these institutions which ostensibly had a democratic functioning but in reality were administered on factors more personal to a state where they lacked the internal strength to resist any attempt at their perversion by outside forces.

The ‘extra-constitutional source of power’ recognized this factor and played on it skilfully. These forces in turn had recognized in the concept of Sanjay Gandhi just the additional impetus they needed for themselves. The implementation of the five-point programme became the yardstick of the competition between the various power groups. The number of trees planted, houses demolished and sterilizations done became the measure of closeness of these various groups to Sanjay Gandhi.

Tag: Ajoy Bose

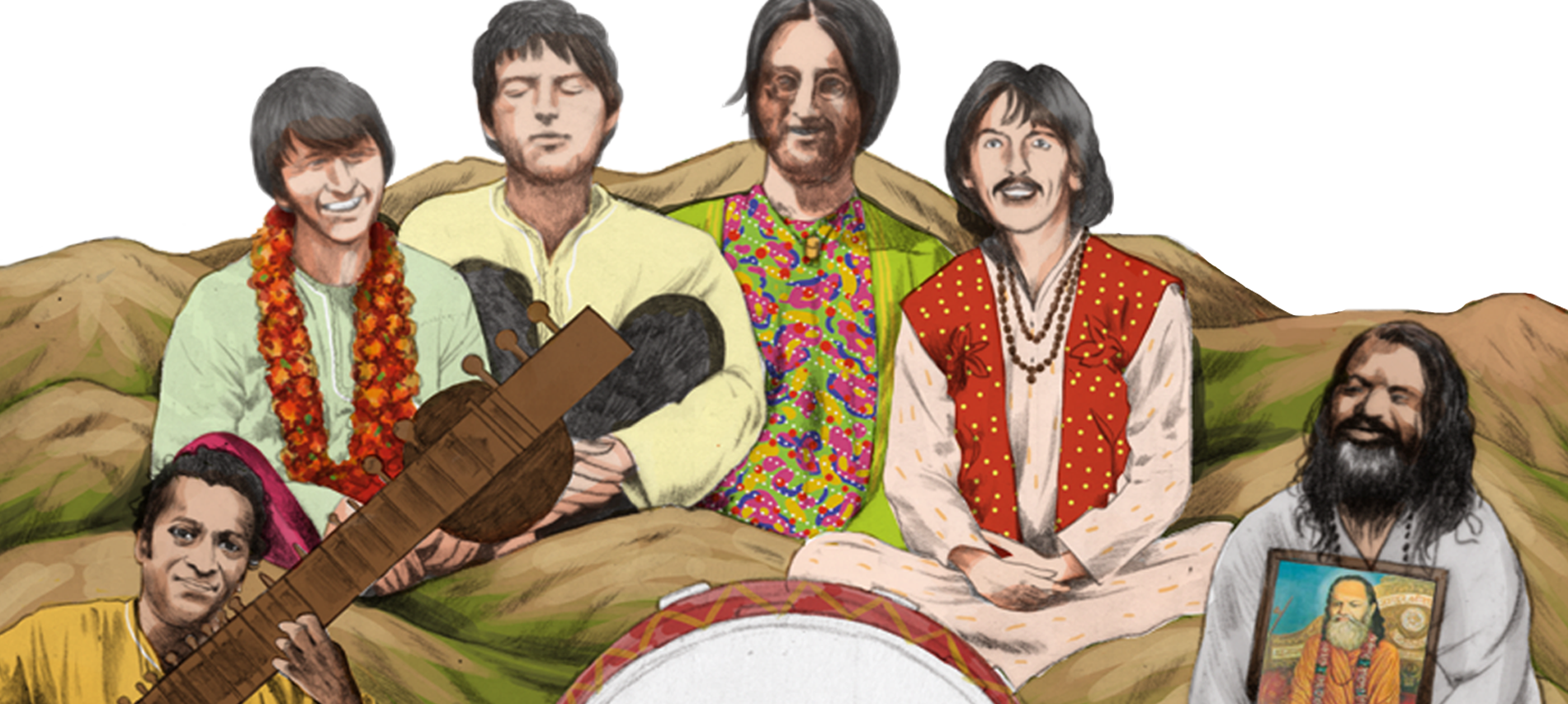

The Beatles and their Time in India

“The Beatles arrived in Rishikesh in February 1968 and settled down in the Maharishi Mahesh Yogi Ashram to learn Transcendental Meditation.” Ajoy Bose, in his book, Across the Universe traces the path the Beatles took to India and the dramatic denouement of their sojourn at the Himalayan ashram. From the book, we extract quotes from the four Beatles and the author about the Beatles’ time meditating in Rishikesh.

The Maharishi (Mahesh Yogi) had effectively cocooned them from the hysteria and hype of their fans and the media. This was the first real opportunity the four had to escape their identity as the most famous rock band in the world. They grabbed the prospect of just enjoying themselves as ordinary folk in a remote, obscure location, far from the relentless daily rush and the fame and fortune that had overwhelmed them.

Of them all, George had the best time from his stay in India. Within a few days in the ashram, George said he was already feeling fabulous.

His great experience was linked to the breakthrough he had in his practice of transcendental meditation.

Paul, who was not all that enthusiastic about Transcendental Meditation when he came to India, was pleasantly surprised at what it could do with his mind. He recalled one particular session that he described as the best he had:

Even Ringo, who had faced a series of harrowing experiences after landing in India, from a pain in his arm to his driver losing his way and from having trouble with an officious doctor at the hospital to his car heating up on the road. To his credit, he did try to take them in his stride and, in the beginning, was actually starting to enjoy the laid-back atmosphere at the ashram.

He and his wife, Maureen however, had been the least enthusiastic about coming to Rishikesh leaving their two young children back in London. And despite him finding his “spiritual home” here, after nine days at the ashram, Ringo and his wife called it quits.

John’s experience was a breakthrough in terms of his song-writing without using drugs or other substances albeit only momentary. John would later recall with some amusement,

The songs did reflect the mess inside John’s mind at that time. They underlined the conflict between his lack of enthusiasm to continue as a Beatle and his fears of not knowing what to do if he wasn’t one.

His song ‘I’m So Tired’, for instance, is a lament over not being able to sleep for three weeks since he came to the ashram, tossing and turning in his bed, smoking like a chimney, as his inner demons tormented him. It revealed his tired mental frame and he would later praise it as one of his better songs from Rishikesh.

True, the boys may have snapped old personal bonds and sown the seeds of the unravelling of the and itself, yet Rishikesh only provided the breathing space for the Beatles to realize their own selves and move on from their past lives and identity as a band. With the Himalayas looming above and the Ganga flowing below, they had gained paradise and then lost it as the modern fairy tale of the four lads from Liverpool reached its closing stages.

Across the Universe: The Beatles in India by Ajoy Bose – An Excerpt

Ajoy Bose has written a widely acclaimed book on the Emergency, For Reasons of State, and Behenji, the definitive political biography of Dalit leader Mayawati. A leading television commentator and columnist, he now uses his formidable investigative skills to look beyond politics, recreating the fascinating journey of the Beatles to India half a century ago. Full of characters and happenings delightful and evil, of comic excess and dark whimsy, Across the Universe: The Beatles in India, traces the path the Beatles took to India and the dramatic denouement of their sojourn at the Himalayan ashram.

Here’s an excerpt from this fascinating read.

—————————

Based on a raga recorded by Ravi Shankar some years ago on All India Radio, George’s song seemed quite independent of the rest of the album in its entirely Indian orientation played by Indian musicians with the rest of the Beatles out of the picture. The Indian musicians were recruited from the Asian Music Circle in Finchley, north London. They were Anna Joshi and Amrit Gajjar on dilruba, Buddhadev Kansara on tanpura and tabla player Natwar Soni. The song also featured lyrics that were overtly spiritual, seeking to explain the Hindu concept of maya, a veil of illusion that needed to be cast aside to find spiritual truth and happiness ‘within you’. The passion with which George played the sitar and the distinctive quality of the song impressed both Paul and John who were getting quite annoyed with his lack of enthusiasm towards the album. Both thought the song was great and did not appear to mind George having Indian musicians take over their studios and, for the first time, leaving them out of a Beatle song. Describing the song as ‘a great Indian one’ John said, ‘We came along one night and we had about four hundred Indian fellows playing here and it was a great evening, as they say.’ He would say later, ‘One of George’s best songs. One of my favourites of his, too. He’s clear on that song. His mind and his music are clear. George is responsible for Indian music getting over here.’ No longer the quiet Beatle, George, his imagination fired by Indian spirituality, could not stop talking about his new infatuation. He appeared along with John on the prestigious television show The Frost Report and gave innumerable interviews to a variety of publications declaring his adopted faith. When he was asked to give his choice of iconic personalities that the Beatles had decided to put on the Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band album cover, the four he chose were all Hindu seers, starting with his favourite Sri Paramahansa Yogananda and the three gurus who preceded him, Sri Yukteswar Giri, Sri Mahavatar Babaji and Sri Lahiri Mahasaya. On George’s insistence, these unfamiliar holy men from a distant land and an obscure faith brushed shoulders on the Sgt. Pepper’s cover with a variety of popular Western icons including Marilyn Monroe, Edgar Allan Poe, Karl Marx, Carl Jung and the champion swimmer Johnny Weissmuller who played Tarzan in Hollywood movies, among numerous others. In less than a year of meeting Ravi Shankar, George had virtually erased from his life all traces of his English working-class roots in Liverpool. The Harrisons became vegetarians, inspired by ahimsa, the Hindu pledge of non-violence to all living things. Pattie would shop at the local health food store in Esher for grains, pulses, vegetables and fruit, cooking not just nut cutlets and stews but also pakora, samosa, lassi and rasa malai. The scent of hash and joss sticks permeated the house. An ornate hookah sat on a low table in a sitting room which had no chairs, just cushions and rugs, according to George’s biographer Thomson. Thomson paints a compelling portrait of a Beatle who had by now fully embraced the culture and creed of a distant land. At his twenty fourth birthday party at his Kinfauns home, he played the sitar and then watched and recorded a concert performed in his honour by the great sarod player Ali Akbar Khan. No other Beatle attended. George wore a traditional cotton kurta and his guests included photographer Henry Grossman and the Byrds’ David Crosby and McGuinn, each arriving with vegetarian dishes for the buffet-style meal. It was, according to McGuinn, a charged occasion. ‘I remember being at that party with him in 1967 and I could feel the room change, there was something happening in the room. I looked at George and asked what was going on, and he said, “I’m transcending.”’ In 1966, a Vaishnavite Indian seer, Swami Bhaktivedanta Prabhupada, had founded a Krishna cult called ISKCON that would sweep the West captivating thousands of young men and women with its evocative ‘Hare Krishna’ chant. The swami asserted that by merely chanting the name of Lord Krishna, devotees could directly connect to the deity. When George came across a record of this chanting, he immediately fell under its spell. He played it to John who too was mesmerised by the repeated and almost hypnotic intonation of ‘Hare Krishna, Hare Rama’, a mantra that is routinely chanted every day by millions of devotees in India belonging to the Krishna sect of Hinduism. For the two Beatles, however, the ‘Hare Krishna’ chant seemed like a magical stairway to divinity. It was also another step towards the quest of the mantra that would take them to Rishikesh. George and John started chanting together whenever they met, forging a second bond in addition to their earlier connection over their shared first encounter with LSD.

For instance, both acid and mantra came together for the two during a sojourn out in the picturesque Aegean Sea in the month of July, when the Beatles went on a bizarre and ultimately abortive hunt to buy a Greek island to build their own kingdom. ‘Somebody had said we should invest some money, so we thought: “Well, let’s buy an island. We’ll just go there and drop out.” It was a great trip. John and I were on acid all the time, sitting on the front of the ship playing ukuleles. Greece was on the left; a big island on the right. The sun was shining and we sang “Hare Krishna” for hours and hours,’ George would fondly reminisce many years later. In that same month George waxed eloquent about both spirituality and India in an interview with Fifth Estate, a radical underground periodical. It would be his most explicit confession of embracing the Hindu faith and Indian culture and is worth quoting in detail. Answering a question on public curiosity about his new zeal for the chant, George expounded on the Hindu theory of Karma:

‘They get hung up on the meaning of the word rather than the sound of the word. “In the beginning was the word” and that’s the thing about Krishna, saying Krishna, Krishna, Krishna, Krishna, so it’s not the word that you’re saying, it’s the sound Krishna Krishna Krishna Krishna Krishna Krishna and it’s just sounds and it’s great. Sounds are vibrations and the more you can put into that vibration, the more you can get out, action and reaction, that’s the thing to tell the people.’