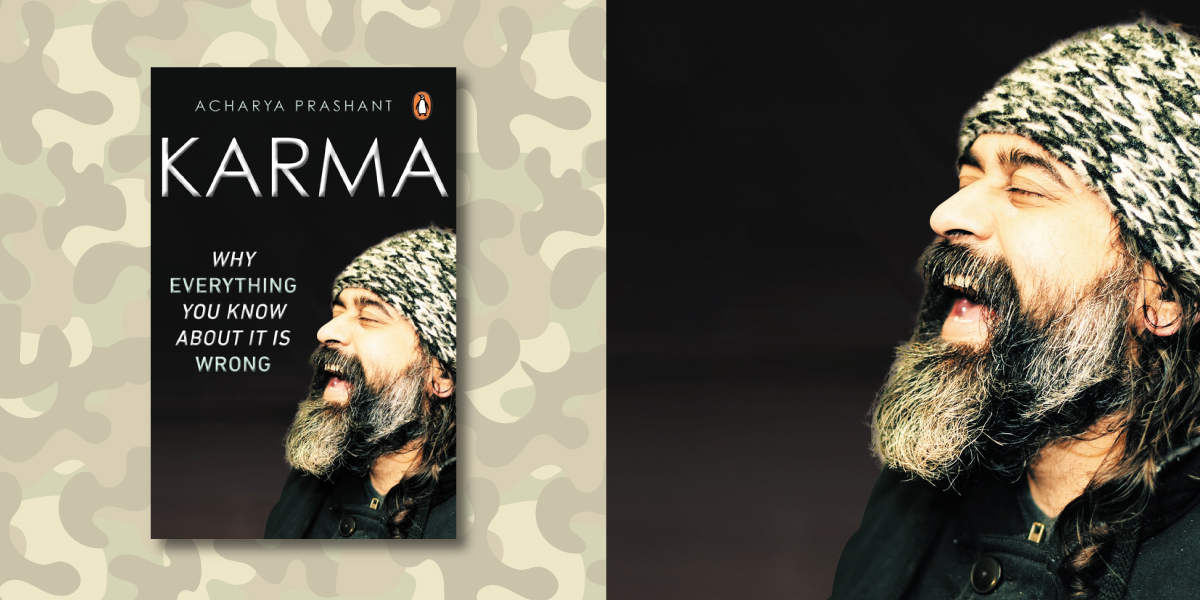

Acharya Prashant, a Vedanta philosopher, an Advaita teacher, and the author of Karma, talks about his transition from the corporate world to the spiritual world. He also answers questions about Karma, a word as common in the spiritual lexicon as in the popular parlance.

After studying at IIM and working in the corporate sector, you took respite into the world of wisdom and spirituality. How did you overcome the difficult period of ‘sorrow, longing, and search’?

The basic inner challenge that life presents to us remains the same, no matter what the circumstances are. The one all pervasive and ubiquitous challenge is to keep doing the ‘right thing’ even in the most difficult situations. So whether one is an MBA student or a corporate employee or a spiritual leader, one has to act rightly – which simply means to not act from a personal centre of greed and/or fear.

There has never been any tectonic shift in my life as such. As an individual, I have always aimed at gradually trekking higher and higher. So, this movement from being a consultant in the corporate world to leading PrashantAdvait Foundation, is to be understood as a process of elevation and not of renunciation. The shift was only towards something higher, towards something more critical and of higher caliber. And the search . . . it has not ended; it is very much there. But yes, the destination has changed.

Your book, Karma, was first spoken and written later. What made you pen down hundreds of questions that you’ve verbally answered in a decade?

Every project that the Foundation undertakes is in tandem with the needs and requirements of those for whose sake it exists. As an organisation and as a socio-spiritual mission, PrashantAdvait Foundation exists to serve and transform contemporary society. And one of its prominent objectives is to liberate spirituality from superstition; which could not have been possible without a total repudiation of the false beliefs linked with the concept of Karma – and this, we know, has been quite successfully achieved with the book. Because the Foundation believes in harnessing each and every medium/platform for the Mission, the idea to write books (and make them reach the masses on a wide scale) occurred quite naturally to us.

Why do you think what people know about Karma is wrong?

Unfortunately, today there is hardly any concept in spirituality which has not been both misinterpreted and misrepresented. The same tradition to which we owe gems like Sri Bhagwad Gita, has sadly become a vehicle for misappropriation. Real meanings and implications of concepts linked with spirituality stand obfuscated and distorted by centuries of misplaced expositions and self-appeasing translations.

So, instead of asking what is wrong in the contemporary definition of Karma, we should be skeptical enough to ask: is there really anything at all that is right about it? Because had there been even a single grain of truth in it, we humans couldn’t have been the way they are – violent, chaotic, depressed, loveless, faithless, and what not!

In your book, you’ve mentioned that one must do what is right and forget about the result. Is there an ideal way to work without expecting results?

It is not the expectation that is to be dropped, but the one with the expectation that must transform. If the actor – the doer, the centre from where the action is happening – is itself the one with desires and expectations, then no attempt to work without expecting results would be successful.

So do not look at the expectations, look at the one who is expecting. And having looked at it attentively, you might find the key to ‘Nishkama Karma’.

In one of the chapters, you have said, ‘Just be wisely selfish and help others’. Can you elaborate on what you mean by being ‘wisely selfish’? Does being selfish not count as bad Karma?

Selfishness is bad when the self is petty; but when the self reaches spiritual heights and the relationship with the other is of Love, then being selfish gets redefined as being compassionate.

Do you plan on writing another book? If yes, what would you like to focus on?

All I can say right now is that I will keep addressing issues that require attention, and books on those issues/topics/concepts will continue to be circulated to the masses.