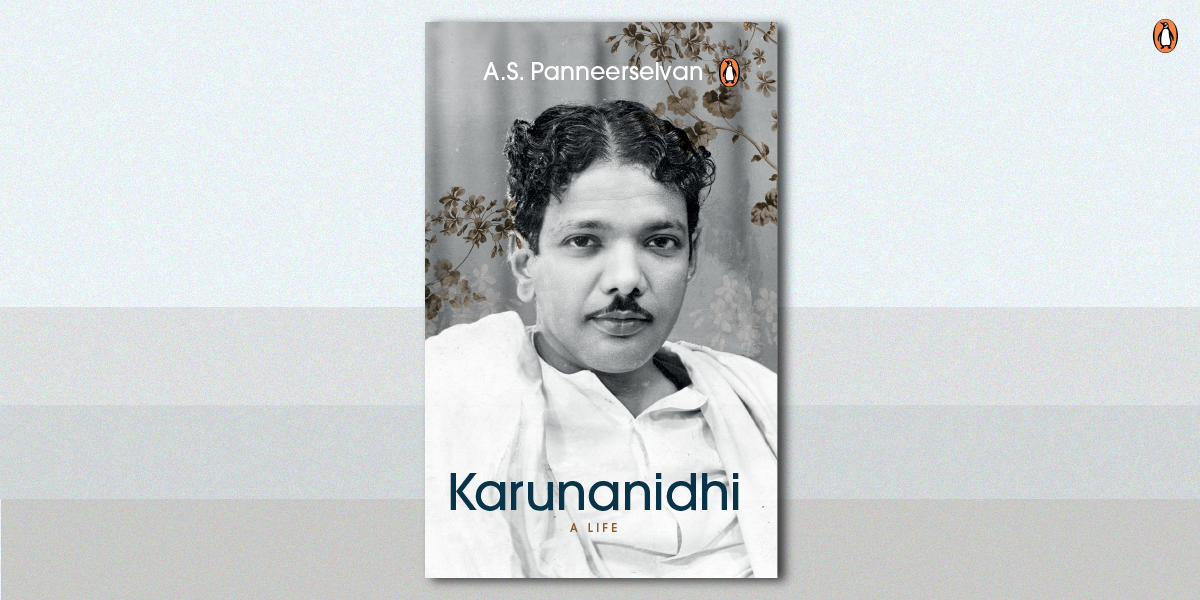

Writer – politician Muthuvel Karunanidhi is amongst the most important political leaders India has ever seen. In Karunanidhi: A Life, author A.S. Panneerselvan tells the story of the man who became a metaphor for modern Tamil Nadu, where language, empowerment, self-respect, art, literary forms and films coalesced to lend a unique vibrancy to politics.

Here is an excerpt from the chapter titled, The Absence of Adolescence.

Like many underprivileged children, karunanidhi’s life moved straight to adulthood from childhood, bypassing the phase of indulgent adolescence. The politicization that began with the anti-Hindi agitation and exposure to the literature of the Self- Respect Movement propelled karunanidhi into becoming an activist right from his days in the second form. The police excesses and the custodial deaths of two anti-Hindi agitators, Thalamuthu and natarajan, had a profound impact on the young karunanidhi.

The late 1930s witnessed varied crises for all the political players: the imperial government was getting ready for the Second World War; the great Depression and its fallout was taking its toll; Mahatma gandhi’s supremacy was challenged within the Congress by the election of Subhas Chandra Bose as the party president for the second time; and the Left was emerging as a distinct political force with its leaders gaining a hold over decision-making in both the Congress as well as other popular fronts. There was also a shift in Dravidian politics with the leadership moving from the wealthy section among the non-Brahmins to Periyar and Annadurai.

The twists and turns of the Left’s mobilization need elaboration in order to understand how, despite its revolutionary aura, karunanidhi remained with the Dravidian Movement’s social reform agenda. in his essay, in the January–March 1984 issue of The Marxist, E.M.S. namboodiripad points out that when the Congress Socialist Party was formed in 1934, the Communist Party of india initially branded it as Social Fascist. With the Comintern’s change of policy towards the politics of the Popular Front, the indian communists’ relationship to the inC witnessed a reversal. The communists joined the Congress Socialist Party (CSP), which worked as the left wing of the Congress. Once they had joined, the Communist Party of india (CPi) accepted the CSP demand for the Constituent Assembly, which it had denounced two years before.1

in July 1937, the first kerala unit of the CPi was founded at a clandestine meeting in Calicut. The five persons present at the meeting were E.M.S. namboodiripad, krishna Pillai, n.C. Sekhar, k. Damodaran and S.V. ghate. The first four were members of the CSP in kerala; ghate was a CPi Central Committee member, who had come from Madras. Contacts between the CSP in kerala and the CPi had begun in 1935, when P. Sundarayya (Central Committee member of CPi, based in Madras at the time) met with EMS and krishna Pillai. Sundarayya and ghate visited kerala several times and met with the CSP leaders there. The contacts were facilitated through the national meetings of the Congress, CSP and All india kisan Sabha.

in 1936–1937, the cooperation between socialists and communists reached its peak. At the second congress of the CSP, held in Meerut in January 1936, a thesis was adopted which declared that there was a need to build ‘a united indian Socialist Party based on Marxism-Leninism’. in kerala the communists won control over the CSP, and for a brief period controlled the Congress there.2

While the Congress in kerala had a distinct leftward tilt, in Tamil nadu it was virtually under the conservative leadership of stalwarts such as C. Rajagopalachari and S. Satyamurti.

Thiruvarur became a microcosm of the play of these multiple forces. Smitten by Periyar’s radicalism and Annadurai’s eloquence, karunanidhi began devouring the entire oeuvre of Dravidian literature. Periyar had already published the Tamil version of The Communist Manifesto in 1937; a number of serious political publications were being published from various parts of the state. Periyar’s Kudiarasu (The Republic) was the key vehicle for dissemination as well as articulating new ideas and planning political mobilization towards an egalitarian society.3

While Muthuvelar and Anjugam were rejoicing at their son’s tireless learning, little did they realize what he was reading about. Textbooks were last on karunanidhi’s reading list. The extensive literature in politics was revelatory for young karunanidhi. For the first time, he realized that he too had two priceless possessions—his oratory and his pen. His first public speech was a clear pointer. it was a school competition. And karunanidhi decided to make a mark. He looked at some of the redeeming features of the so-called villains within Hindu mythology. karunanidhi spoke at length about the friendship between karna and Duryodhana—a friendship that cut across both caste and class.

The speech was well-received, and the teachers developed a new respect for their wayward student. But, what they did not know was the effort that went behind this oratory. karunanidhi worked on the text of the speech for nearly a week; rehearsed the speech frequently before the mirror; changed the words, similes and metaphors to get the rhythm that would alter the art of public speaking in Tamil forever.

He also created his own publication—Maanavanesan (Friend of students). A handwritten fortnightly of eight pages in demy size that dealt with a range of issues—from questioning orthodoxy to exploring the poetics of early Tamil. He and his friends would make about fifty copies of the magazine and circulate it for a modest fee that managed to just cover the cost of the paper. Years later, when i met him at Murasoli along with Kungumam editor Paavai Chandran for a short interview for the Illustrated Weekly of India, karunanidhi said the handwritten journal was a great learning experience. ‘We could not afford to make any spelling mistakes or grammatical errors. A single mistake meant rewriting fifty copies. The sheer labour of correcting made me write a very clean first draft, without any corrections or overwriting,’ he recalled. He also took pains to mail a copy of the magazine to the leaders of the Self-Respect Movement.

But not all of karunanidhi’s icons were happy with the handwritten magazine. Bharathidasan, the well-known poet and a life-long supporter of the Dravidian Movement and karunanidhi, called it a waste of time and effort. He told karunanidhi: ‘The madness of expecting changes from handwritten publications can only be compared to the madness in thinking that development will happen due to spinning charkhas.’

Muthuvel Karunanidhi was ardent as a social reformer and unrelenting as an opposition leader. To read more about him, his life and his work, get your copy of Karunanidhi: A Life.