How do you go from being a shopkeeper to multi-billionaire in forty years?

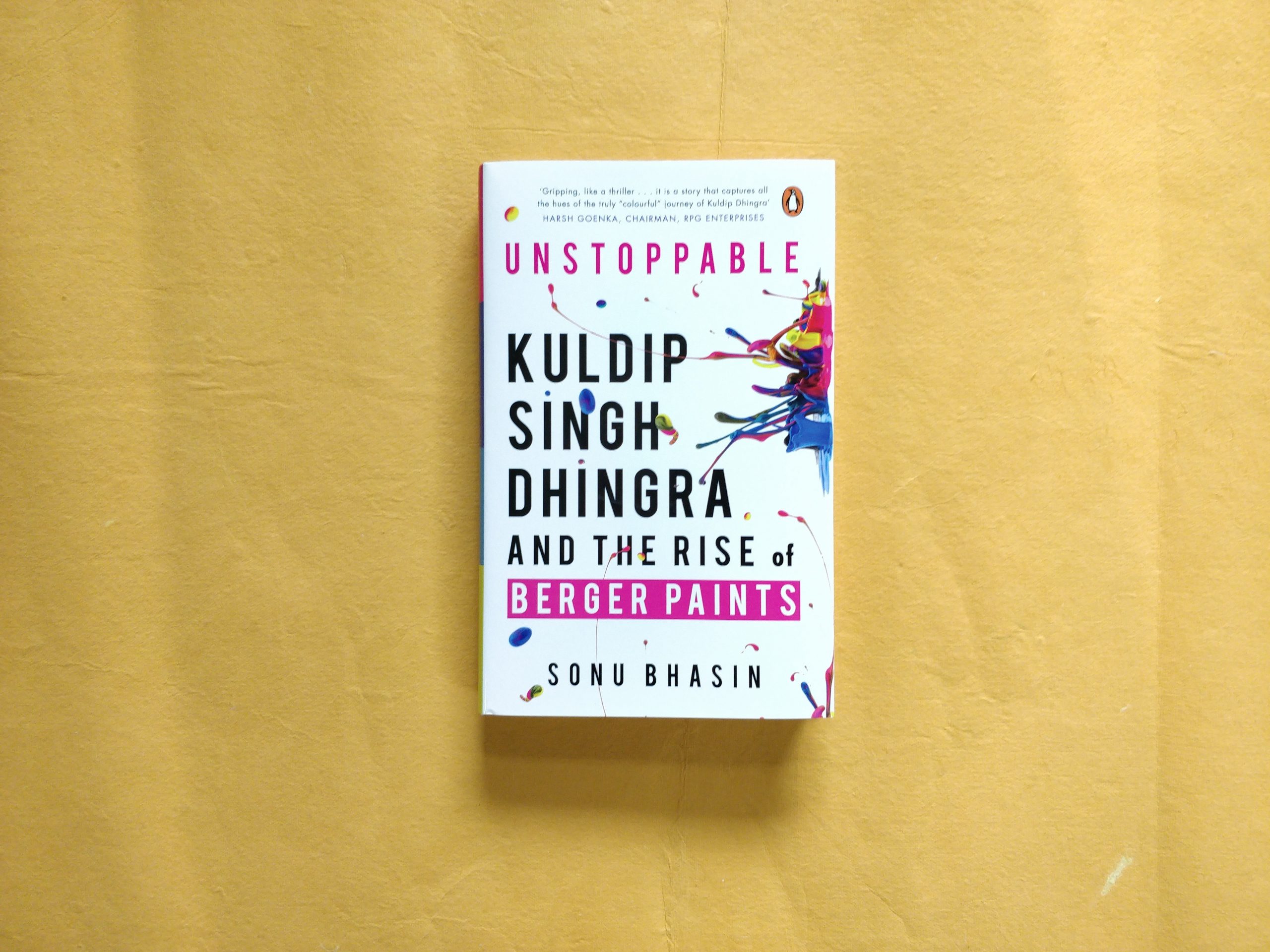

Kuldip Singh Dhingra, the patriarch of the Dhingra family and the man credited with building Berger Paints, has remained a mystery. He is low-profile, eschews media and continues to operate from a small office in Delhi. In this candid and captivating biography Kuldip reveals his story for the first time – Unstoppable by Sonu Bhasin narrates what a man can achieve if he pursues his dreams relentlessly.

Read an excerpt from the book below:

——————————————-

The collapse of the Soviet Union was the last thing on Kuldip’s mind when he sat down to have his coffee and opened the financial daily for his morning update one late January morning.

‘I saw the news about Vijay Mallya selling Berger and I knew immediately that I had to buy that company,’ said Kuldip. ‘We had oodles of money. How much of property could I buy? We had to buy a business,’ he continued. He had been speaking with Gurbachan over the last few months about their future. The Rajdoot business had grown during the last ten years, but it was still in the range of Rs 10–15 crore annually.

‘We had many small factories, all under Rs 1 crore to reap the benefit of small scale. But the name Rajdoot was not a premium brand,’ explained Gurbachan. The two brothers had been bouncing around ideas about buying a running paints business.

‘We had been in discussions with some other paint companies.I even went to London to discuss the matter with the foreign owners of a well-known paint company,’ said Gurbachan. UK Paints was not a known company, Rajdoot was a small brand, and the Dhingras were low-profile people. The foreign promoters had a large business worldwide and were selling only their Indian operations. They did not like the idea of selling out to what they thought was a smaller company run by someone who did not understand corporate culture and had been running a shop in Amritsar till a few years ago.

‘I got the feeling that he was not even happy talking to us about it,’ said Gurbachan without any self-pity. The foreign owners eventually sold their company to a better-known and a bigger industrial family of Delhi.

‘But could you not use the money to focus on Rajdoot Paints which was your own company anyway?’ I asked Kuldip.

‘But Rajdoot would have to be managed by me if I wanted it to become even half as big as what Berger was then. And I simply did not have the time. Berger was a professionally managed company and had a good team—at least that is what I thought at that time. I believed that once we bought the company, apne aap chalti rahegi [it will run by itself],’ explained Kuldip.

Kuldip certainly did not have any time to manage any other business except his export business. The export business had given him ‘oodles of money’ as Kuldip put it, and it had also given Kuldip a world view of business. He was dealing with a cross section of professionals from around the world and he had become used to large businesses. Rajdoot, though one of the fastest-growing paint companies in India in the late 1980s, was at best a regional company. It was not a star or even an emerging star on the horizon. Kuldip, on the other hand, had become used to being a star! He was feted as an important businessman in the Soviet Union and was known as a big exporter in India. Should the export business wind down, he knew that he would continue to be very wealthy but he would feel stifled by the small, regional business of Rajdoot. He did not want to be clubbed in the ‘Others’ category in the domestic paints business. He realized he needed a larger canvas for his domestic business dreams.

‘I was doing business in hundreds of crores with the Soviet Union. And the total turnover of Rajdoot then was just Rs 10–15 crore,’ said Kuldip.

While he was exporting a variety of items to the Soviet Union, at heart he remained a paints-man. ‘There was only one business I understood well and that business was the paints business,’ said Kuldip. So when he saw the headlines about Berger Paints being sold, the instinct bulb in his head burnt bright.

Unstoppable narrates what a man can achieve if he pursues his dreams relentlessly.