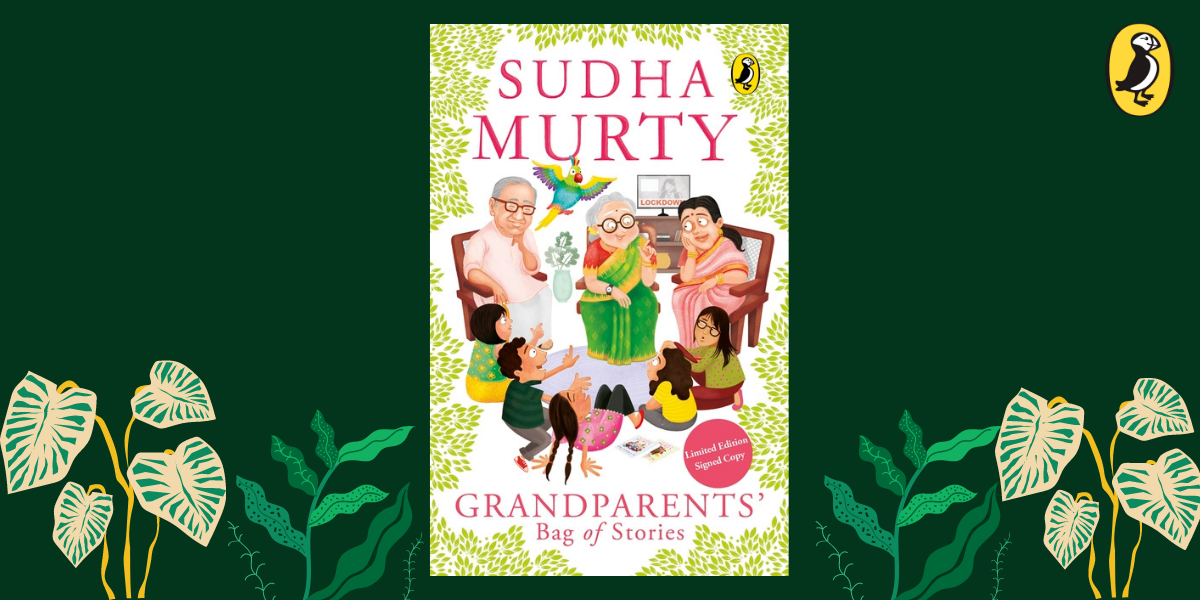

Following the trail of the best-selling Grandma’s Bag of Stories, India’s favourite author Sudha Murty brings to you this collection of immortal tales that she fondly created during the lockdown period for readers to seek comfort and find the magic in sharing and caring for others. Wonderfully woven in her inimitable style, this book is unputdownable and perfect for every child’s bookshelf!

It was a pleasant afternoon in March. Ajji and Ajja were glued to the television. The worry on their faces deepened as they heard increasingly distressing news about the coronavirus situation. Ajja turned to Ajji, ‘The virus started in China, but look at what has happened. It has spread all over the world, becoming a pandemic!’ The anchor on the television announced, ‘The government is asking people to isolate themselves and follow social distancing protocols. All schools will be closed until further notice.’ Ajji’s thoughts turned to her grandchildren in Bangalore and Mumbai. The sound of an autorickshaw coming to a stop outside the house interrupted her thoughts and the bell rang. Ding-dong! Ajji opened the door and saw Kamlu, Ajja’s sister, and her granddaughter Aditi. Ajji was delighted and surprised to see them. ‘Come inside,’ she said. Kamlu Ajji smiled as she took the bags out of the autorickshaw. ‘Why didn’t you tell us you were coming?’ asked Ajji. ‘We would have picked you up from the railway station. Kamlu Ajji and Aditi entered the house. ‘Kamlu, why did you make this trip with the deadly virus around?’ Ajja demanded, concerned. ‘Oh, I didn’t know coronavirus had reached here too. Isn’t it time for the cart festival now? I haven’t seen it in so long! Aditi has her holidays now and her mother is working from home, so it is hard to keep her engaged. I thought she might enjoy the festival and brought her with me. Besides, I wanted to give you a surprise!’ Nine-year-old Aditi stood shyly behind Kamlu Ajji. ‘Come, child. Sit,’ said Ajji, inviting her with love. They all went to sit in the living room, and just then, the phone rang.

Ajji picked it up. It was her daughter, Sumati, from Mumbai. ‘Amma,’ she said, ‘I am sending both the kids to you in Shiggaon.’ ‘I’d be happy to have Raghu and Meenu, but what happened?’ ‘With Covid-19 spreading like wildfire, the schools are closing down for some time and no one knows when they will reopen. Most people live in small apartments in Mumbai and it is almost impossible to keep children from going outside. Moreover, we are working from home and can’t tend to their needs all the time. So we thought about it and spoke to Subhadra to see if I could send Raghu and Meenu to her, and she said yes . . .’ ‘All the children can come here, Sumati!’ Ajji interrupted her. ‘I knew you would say that and that’s why I called. Subhadra has also agreed to send her children to Shiggaon to be with you. You have a large compound around the house and there’s plenty of fresh air and space to move around. This way, the kids can be with you all and not get bored since they will be able toplay with each other. Now, don’t hesitate to be frank. Tell me, will it be a problem for you to handle the four of them without sending them outside the house?’

‘No, Sumati, that is not a problem at all! My worry is—how will they come here?’ ‘We will take care of that, Amma! Raghu and Meenu have already taken a flight from Mumbai to Bangalore today and are about to reach Subhadra’s home,’ said Sumati. ‘They can come to Shiggaon tomorrow and stay for a few weeks.’ Ajja, who had been listening to Ajji’s side of the call, took the phone from her and spoke to Sumati, ‘Don’t worry, child. Kamlu and her granddaughter Aditi are also here. Send the children.’ Almost immediately, there was another call from Bangalore. Subhadra was on the line. She said the same thing. ‘My parents have already taken Anand with them, but Krishna and Anoushka want to see you and stay in Shiggaon. I have spoken to Sumati already and the four children will reach your home tomorrow. Our office manager has offered to drive them from Bangalore to Shiggaon, but he will come back immediately because there is a lot of work to be taken care of before things get worse, as is expected,’ said Subhadra.Ajji ended the call and looked at Ajja. ‘I am happy to hear that our grandchildren are coming, but I am concerned about the coronavirus situation. Will you call the temple and check if the cart festival is still going ahead as planned?’

Ajja nodded and dialled the temple’s number. While calling, he remarked, ‘It is unlikely that they’ll go ahead with the festival. We had a committee meeting yesterday and I suggested that we skip the cart festival this year, but others rejected my opinion. They felt that we shouldn’t worry because the coronavirus hasn’t reached us yet. I disagreed. Conducting the festival will be akin to giving coronavirus an invitation to come here.’ Kamlu Ajji’s face fell. ‘Instead of surprising you, I am the one who is surprised and disappointed. I think I will go back after a few days.’ Kamlu Ajji and Ajji were close friends. Ajji was pleased that her friend was with her. ‘You are not going anywhere,’ she said emphatically. ‘Cart festival or not, you are staying here with us.’ Ajja turned out to be right. The festival had been cancelled. Kamlu Ajji turned to Ajji and announced, ‘I am going to take charge of your kitchen. I love cooking. You can rest for a few days.’ Ajja added, ‘If the situation with respect to the coronavirus gets worse and a lockdown is announced, then we should not bring any outside help for the workaround the house. Let’s share the work. ‘Yes, I agree. We can’t call anyone,’ said Ajji. ‘Once the children arrive tomorrow, I will assign household chores to all of them. They will also help us.’

Ajji went to the storeroom to check if she needed to get more groceries. Ajja followed her and remarked, ‘Some places have already announced lockdowns. If we have a lockdown here too, there will be many people who will not get enough food. We must help and lend a hand when the time comes. Please order extra rations and keep them in the storeroom. We may need them to feed other people.’ Ajji began to make a grocery list, and Ajja dialled the number of the local grocery shop for a home delivery. Meanwhile, Aditi sat nearby, reading a book. She was happy to hear that four of her cousins were coming. The next evening, Raghu, Meenu, Krishna and Anoushka arrived with great excitement. They loved visiting their grandparents’ large and spacious home where they were pampered and allowed their freedom. The office manager dropped the kids and promptly left.

As soon as they entered the house, Aditi squealed and joined them immediately. Anoushka had grown tall. Ajji announced, ‘Anoushka, you are the tallest of the girls now!’ The children had brought their schoolbooks, and many bottles of sanitizer and handwash refill packs. They seemed happy to be away from their parents with no classes or teachers to worry about. They told their grandparents how sanitizers were being used everywhere in their schools before they had closed and in their apartment blocks in Mumbai and Bangalore, including even the lift. ‘Have things become that difficult there?’ Ajji asked, concerned. ‘Yes,’ said Raghu. ‘The government is taking many precautions and has become quite strict.’ ‘Children, what would you like to eat for dinner?’ ‘Something light, Ajji, as we had heavy snacks a short time ago,’ said Krishna. ‘Then I’ll make some special rice today—perhaps methi rice,’ said Kamlu Ajji. ‘It is easy to digest, delicious and good for supper.’ The children agreed and Kamlu Ajji headed to the kitchen.

Ajja switched on the television. Discussions about quarantine and social isolation continued on all news channels. The prime minister was going to address the nation shortly. Ajja looked outside the window. The evening was turning into night. He sighed, ‘Children, this is serious now and we all must stay inside the walls of the house. You can only go as far as the wall of the compound. We must not go out for any reason.’ In less than an hour, Kamlu Ajji had made an excellent dish of methi rice with cucumber raita. Proudly, Ajja said, ‘All these vegetables are from our vegetable garden. We use natural fertilizers and grow organic vegetables that taste much better than what you get outside.’ After dinner, the children helped Ajji in laying down five mattresses next to each other. Each of them chose the bed they wanted. Once it was done, Raghu turned to Ajji, ‘You have not completed your daily routine.’ Ajji smiled. She knew what he was referring to. ‘A story, Ajji,’ pleaded Anoushka. ‘A story a day keeps alldifficulties away . . .’Everyone chuckled. ‘Okay, I will tell you a story. It is a tale of what you ate for dinner—about rice. Rice is part of our daily diet and we can’t imagine living without rice or wheat today.’ The children gathered around both the Ajjis. Ajja sat on a chair nearby, watching the television. The prime minister announced, ‘A lockdown will be imposed starting midnight. Everyone must stay home for the next few weeks.’ It was evening and already dark outside. The children began listening to the story earnestly, just as the quarantine period was formally declared. Ajja muted the volume on the television, but continued watching. ‘Let us all listen to the story of how rice came to earth,’ said Ajji.

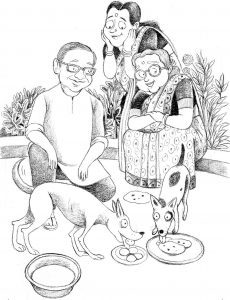

Ajji put biscuits, rice and chapati in a bowl and kept water in another bowl just outside the gate. The two dogs looked at her and attacked the food greedily, gobbling it down in minutes. Then they drank the water, wagged their tails to thank her and ran away.

Ajji put biscuits, rice and chapati in a bowl and kept water in another bowl just outside the gate. The two dogs looked at her and attacked the food greedily, gobbling it down in minutes. Then they drank the water, wagged their tails to thank her and ran away.