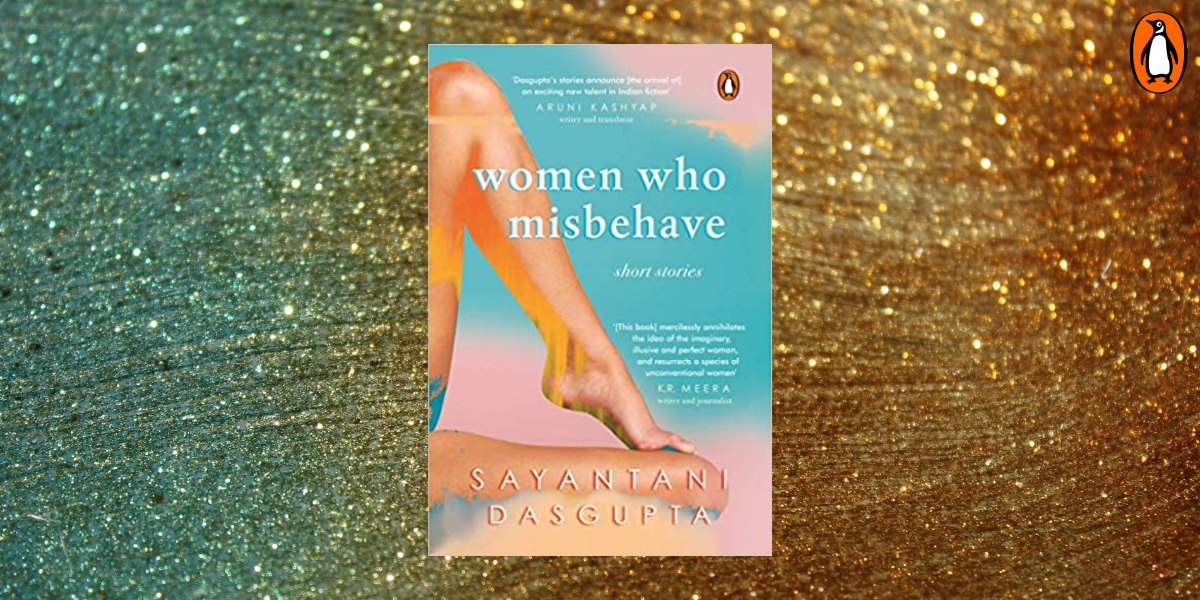

Women Who Misbehave, much like the women within its pages, contains multitudes and contradictions-it is imaginative and real, unsettling and heartening, funny and poignant, dark and brimming with light.

At a party to celebrate her friend’s wedding anniversary, a young woman spills a dangerous secret. A group of girls mourns the loss of their strange, mysterious neighbour. A dutiful daughter seeks to impress her father even as she escapes his reach. A wife weighs the odds of staying in her marriage when both her reality and the alternative are equally frightening. An aunt comes to terms with an impulsive mistake committed decades ago.

In this wildly original and hauntingly subversive collection of short stories, Sayantani Dasgupta brings to life unforgettable women and their quest for agency. They are violent and nurturing, sacred and profane. They are friends, lovers, wives, sisters and mothers. Unapologetic and real, they embrace the entire range of the human experience, from the sweetest of loves and sacrifices to the most horrific of crimes.

Here is an excerpt from the book, Women Who Misbehave:

It is a Friday evening, but you can’t head home and settle in front of the TV with beers from your fridge and mutton biryani from the dhaba across the street. It’s already been a long day and doesn’t seem to be anywhere close to ending. You now have to go to your friend’s home for a dinner party. Well, she isn’t really a friend. She is a former colleague, so you can blow it off. But you’re not an asshole, and she has invited you to celebrate the three- month anniversary of her wedding. You care neither for the occasion nor the husband. Still, you board an auto and head her way because you are a good person.

The two-storeyed bungalow-style home has a wrought- iron gate and a small garden. It is conveniently located a hop, skip and a jump from the bustling Hauz Khas market. You can’t help being envious. They probably just stand on their balcony and holler for all sorts of vendors to come rushing with platters of pakoras, samosas and hot jalebis straight from the fryer. You, on the other hand, live in the hinterland by yourself because that’s what you can afford on your salary. Which is really why you tip the dhaba boys so generously every time they deliver your order. You cannot risk angering the one source of palatable food in your neighbourhood.

You reread the directions your friend texted you this morning. You are to go straight upstairs and neither loiter around the ground floor nor accidentally ring the bell. The husband’s widowed mother lives on the ground floor, and you’ve been warned that she has little tolerance for anyone under the age of seventy.

You walk past the tidy square garden until you hit the mosaic staircase. With each step you take, the strain of jazz music grows stronger. The stairs lead you to a heavy black door, and you let your finger hover over the bell. You’re no expert, you don’t know the names and types of woods in this world, but you can tell this is expensive. And you’re happy for your former colleague, you truly are. After all, how many people your age, and with practically the same goddamned salary, get to disappear behind a door like this every evening?

You take a deep breath and press the bell even though your throat feels like it is closing in, like flowers whose petals clam up at night. We are done preening for you, sucker! You hear the momentary lull in conversation, but you have already recognized the voices. You quit these people a few months ago in pursuit of a flashier salary, but now you have to spend an entire evening with them. You press the doorbell again. Urgently. As if you are here to take care of serious business.

Tanu opens the door, her face awash with happiness. Marriage hasn’t changed her, at least not on the outside. She is dressed simply in her usual blue jeans and a pale T-shirt, her outfit of choice for practically every occasion. She gives you a hug and you breathe in a cloud of familiar smells— lemon verbena soap, sandalwood perfume. Mahesh slides up beside her, his shaved head hovering like an egg over her bony shoulder, his arm possessively gripping her tiny waist. He smiles too and says, ‘Welcome, welcome. Please come in.’

You say ‘thank you’ although you can’t help but think that the deep lines under his eyes and the tight way his skin stretches over his face make him look less like Tanu’s husband and more like a creepy uncle. Somehow, the fifteen-year gap between them is more pronounced this evening than it was on the day of their wedding, when you saw him for the first time. But you were too drunk then, and so all you remember is how after a few drinks Mahesh began telling everyone what he would like to do to every man who had ever hurt Tanu. You had giggled along with the others, but, secretly, you had wondered what it might feel like to be the object of such passion. You catch Mahesh’s eyes sweeping over your black shirt. His gaze doesn’t linger on your breasts—maybe if you weren’t so flat-chested things would be different—but out of habit, you surreptitiously glance down to check that the buttons haven’t come undone.

‘Black really suits you,’ Mahesh says. You laugh because you haven’t mastered the art of accepting compliments. You follow Mahesh and Tanu into the drawing room where a cluster of familiar faces acknowledge you with varying degrees of nods and smiles. It’s a smartly put-together room—stainless steel and white leather, with tasteful accents of bamboo. Two love seats face an enormous couch and the side tables have neat stacks of expensive-looking coffee-table books, lit up just so by stark, Scandinavian-looking lamps. On one of the love seats, Pia and Projapoti are smashed next to each other, gazing into a glossy book of black-and-white photographs of umbrellas. Their romance is as new as it is tumultuous, so you tell yourself to forgive them if they ignore you. But they don’t. Pia looks up to give you a cheery wink and Projapoti, who took you under her wing when you first joined the company, sets downs her drink, stands up and wraps you in a hug.

Rani is sprawled on the couch. Swathed in a voluminous pink and red sari, she looks like a porcelain doll. Her eyes are closed; her lips are pressed together. She is the picture of calm, a far cry from the perpetually anxious person she is at work. Auro, the only other man in the room besides Mahesh, is on the other end of the couch. He was hired to replace you, and you trained him during the last week that you were there. But from the cocky, two-fingered salute he gives you, you would think it was the other way round. He slides towards Rani to make space for you on the couch. You sit beside him, and as if to deliberately ignore your irritation, Auro stretches languorously and crosses his long legs at the ankles.