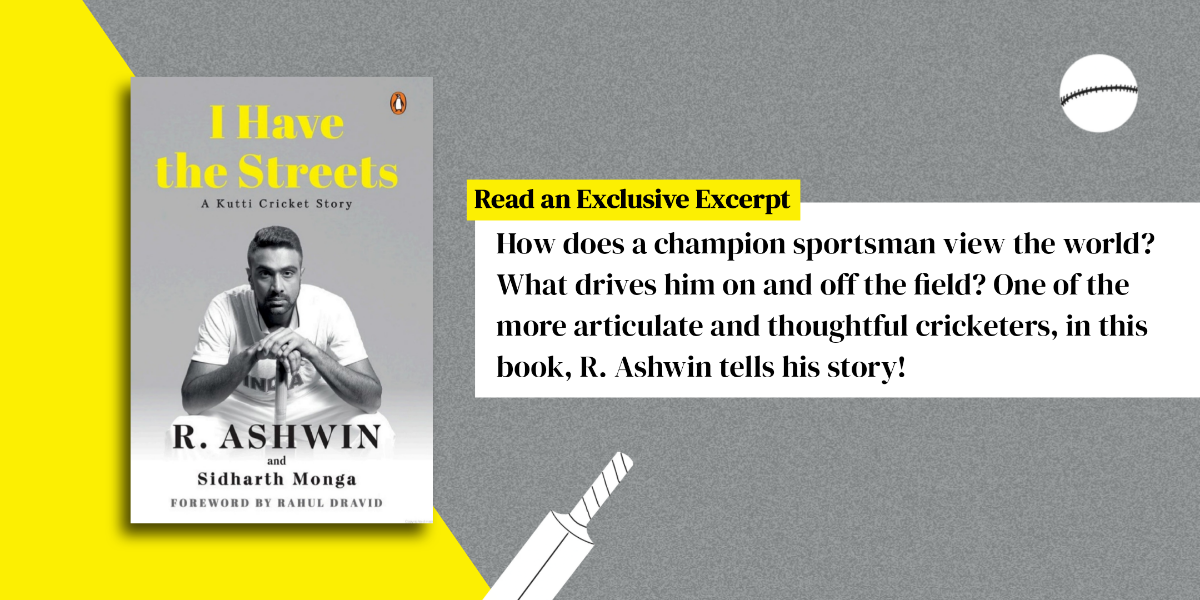

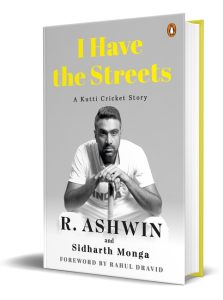

R. Ashwin, one of India’s greatest cricketers, shares his incredible journey in I Have the Streets, co-written with Sidharth Monga. Ashwin not only talks about his amazing cricket achievements but also tells the story of his struggles with health as a child, the strong support from his family, and his love for cricket growing up in the streets of Madras.

Read this exclusive excerpt to get a glimpse of Ashwin’s early cricketing days full of hard work, family sacrifices, and his deep passion for the game.

***

I am ten when Appa’s teammates at Egmore Excelsiors ask him to bring me around to play for them. I have been taking formal coaching, and my batting is coming along nicely. Appa fears I will get hit by the hard cricket ball, so he keeps resisting. I am not puny, but I don’t have the muscle mass to go with my height. With all my wheezing and vomiting bouts, I struggle to keep any food down. Two years later, he finally gives in.

At twelve, I make my Madras leagues debut for Egmore Excelsiors in the fifth division. My first kitbag is the same improvised pads-around-the-bat contraption. The bat is Appa’s Simon Tuskers, fully taped and gutted. In my second season, I have scored a century. My main utility, though, is to field at slip and short leg. I take a lot of catches. And blows, because fifth-division spinners are quite erratic with their discipline, thus endangering their short-leg fielders.

Now, instead of protecting me from the cricket ball, Appa is following the coaches’ advice that tennis-ball cricket will ruin my game. So, he tries to ration those matches for me. To help me rid myself of the fear, he installs a net in the house. The surface of the first one is quite rough, so he gets it redone to a smooth finish. During a family function at home, he asks the videographer to film me while batting. It comes back like a wedding film.

Appa throws balls at me from a close distance so that I don’t fear the thirty- to forty-year-old pros in the leagues, who can be a terror with the unpredictable bounce of the matting pitches we get in the fifth division.

Batting against them is not even the scariest part. It is the fear of letting your teammates down and getting admonished for it. The first season is really intimidating. I’m not sure know what they will say or where they will make me stand on the field. I keep fearing misfielding or dropping a catch. No matter how poorly the team has bowled, if a young kid makes a mistake on the field, that kid becomes the reason they lost. They make you run from deep midwicket to deep cover between balls. To score a hundred and compete against these men in just one year tells me I might have something in me as a cricketer.

Appa recognizes it and wants me to be tested against the best. He gets me enrolled in as many academies as he can. Some coaches he pays; others he takes favours from, using his connections. Former India wicketkeeper Bharath Reddy now handles operations at Chemplast. As the name suggests, it is a chemical company in Madras. The name doesn’t give away, though, that they field two strong teams in the higher divisions of the Madras leagues: Jolly Rovers and Alwarpet CC. He also runs his own academy, where I train.

By thirteen, I am a bit of a big dog at the Bharath Reddy Academy. Appa is tempted to get me to the seniors’ nets, among the Jolly Rovers probables, to test me. One of the quicks knocking at the Jolly Rovers door is L. Balaji, who is unplayable on matting pitches. He bowls rockets that don’t even come straight at you. His outswingers are hard to follow; his inswingers hit batters in the chest and not the pads.

The thing with Appa, though, is that he will never undermine a coach by making such a demand. A coach is almost like a senior police officer whose orders must be followed without question. The other thing about Appa is that he will not give up. When this inner conflict of his becomes apparent, Amma comes to the rescue by offering to make that call to Bharath Reddy. However, Bharath Reddy still ends up giving Appa a piece of his mind when he sees us. Facing Balaji at thirteen is a death wish, he says.

Appa is slightly bolder at the other academy, Sishya, run by P.K. Dharmalingam, who does cricket shows on TV. He is the man Kapil Dev credits with teaching him how to take catches running back and over his shoulder, the most famous one being that of Viv Richards in the 1983 World Cup final. After two months of persistence, Appa finally convinces Dharmalingam to let me bat against the senior quicks. There is no sight screen; we are on a matting surface with concrete underneath, and this big, fast bowler runs in. The first ball I face hits me in the chest, and I am down. I have to be carried out of the nets.

For a few days after the incident, I wake up in the middle of the night to see a hand near my nose and mouth. It’s Appa checking to see if I am still breathing. He feels guilty and is worried about pushing me too far. He scales it back a little but doesn’t give up on repetitions. Repetition to build muscle memory is a big thing with him. A day before I have a match, he sits on a sofa and keeps throwing balls at me. At least 200. ‘Bend that knee when you play the cover-drive.’ He has also tied a ball to a rope that hangs from the ceiling so that I can keep repeating my shots. This way, I don’t need a person to throw balls at me, nor do I need someone to run after the ball.

There is one problem, though: the ball keeps hitting the fridge before coming back to me. This fridge was gifted to Thatha by his father-in-law when it was rare for homes to have one. Thatha continues to treasure it. The fridge has become the trigger for the outpouring of all the tension between Thatha and Appa. Thatha doesn’t like Appa investing so much time, money and emotion in my cricket. Especially with my health problems.

On this one day, I am getting in a last-minute knock before a league game. As I keep hitting the fridge, tempers flare between Thatha and Appa, who cushions me from it. ‘You have no value for money. You don’t know how expensive this fridge is.’

In an attempt to shield the fridge, Appa tries to get in the way of a shot I play, but my bat swing ends at his forehead, splitting it open. Immediately, blood gushes out. The floor turns red. I freeze, drop the bat and stand there not knowing what to do.

***

Get your copy of I Have the Streets by R. Ashwin and Sidharth Monga on Amazon or wherever books are sold.