Today is an age of experimental and innovative entrepreneurship. Business strategy is changing fast, and so are customers’ expectations. It is more imperative than ever to keep up.

As the business-world becomes increasingly competitive (and creative), treating your customers is no longer enough. There are new rules that have emerged, including taking care of employees. Happy employees make happy customers, and happy customers tend to be loyal.

‘The New Rules of Business’ by Rajesh Srivastava presents insights and anecdotes to explore how businesses can grow in the new-age world. Find out how growth and success is an achievable milestone, even if you are new to the field, in an excerpt below.

**

Pivot to Unlock Growth

Business history is littered with examples of the initial strategy of an enterprise invariably failing. Successful enterprises don’t give up when their initial strategy proves ineffective. They pivot as many times as required, till they hit upon a successful strategy: either by chance, through superlative thinking or from a competitor’s mistake or by sheer luck. Once the successful strategy is discovered, the enterprise drops anchor.

Implied in this approach is an axiom: it is unwise to put all resources—financial and non-financial—into the initial strategy. Enterprises should hold back sufficient resources for subsequent strategic pivots they might have to undertake along the way till the successful one is identified. An enterprise, therefore identifies and places a bet on the best initial strategy and invests sufficient resources to make it a success. But it also holds back enough resources in case the initial strategy does not work out and the enterprise has to pivot to arrive at another strategy.

Enterprises that ignore the pivot strategy could make mistakes at a great cost to themselves and their shareholders.

Are there examples of enterprises that have embraced the pivot strategy to lay the foundation for business success?

Wikipedia

Wikipedia1 leads the list. It ‘pivoted’ its way to becoming the world’s largest collaborative, free encyclopaedia. In March 2000, Jimmy Wales, the founder of Wikipedia, launched an online encyclopaedia and called it ‘Nupedia’. As was the norm then, he assembled an advisory board of experts to mentor this project. They in turn developed an intensive acceptance and editing process that included multi-step peer review process to control the content of the articles.

After twelve months, merely twelve articles were written, despite many contributors evincing interest. The strategy of having experts to control and drive the project was clearly not working. Wales needed to pivot, and quickly.

In 2001, a second free online encyclopaedia was launched where anyone could contribute. It was called Wikipedia. It operated on the principles of software industry where a collaborative approach was followed. Work released at the earliest possible opportunity and refined subsequently. This process is called ‘beta testing’. Leading software companies are in a state of perpetual beta: they are striving for continuous improvements. A leading proponent of this strategy is Google.

80 per cent ready. And then based on user feedback, it keeps improving the software, live.

Wikipedia too released the earliest possible version of an article, letting several people work simultaneously to rapidly refine it. The new pivot got traction and Wikipedia, as we know it, was born. Nupedia, which decided to remain rigid and not pivot, shut shop in 2003.

**

Author Rajesh Srivastsava brings to this book three decades of corporate experience to present advice that is both accessible and actionable.

Feed your entrepreneurial spirit by getting a copy of the book today!

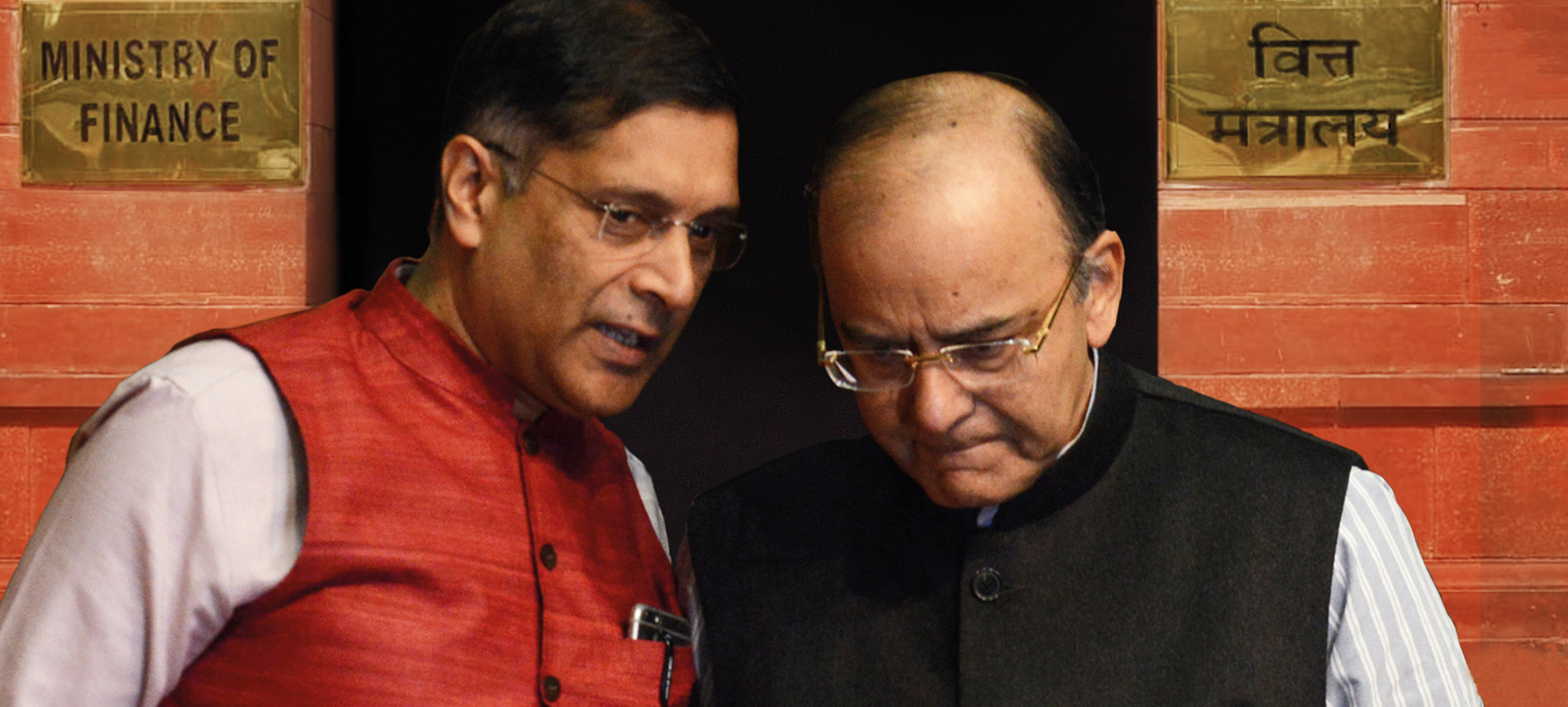

Recognized as one of the Top 100 Global Thinkers according to Foreign Policy magazine, Arvind Subramanian’s

Recognized as one of the Top 100 Global Thinkers according to Foreign Policy magazine, Arvind Subramanian’s