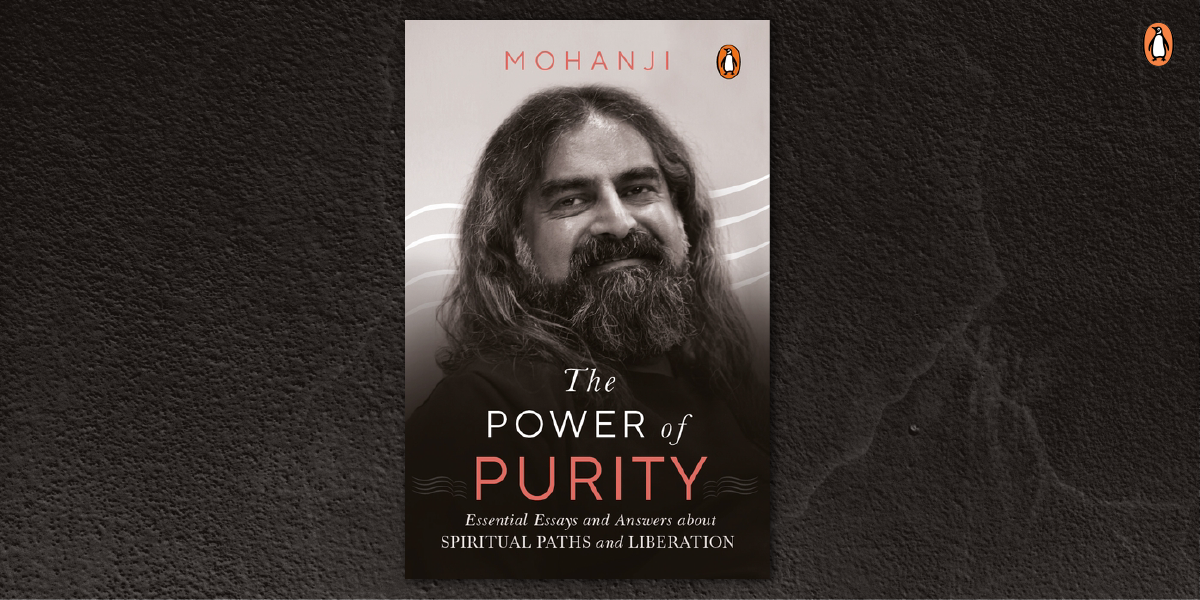

With our birth begins our life cycle and it ends with our death. We all are transitory beings. We can own nothing on Earth on a permanent basis. When we understand that all relationships, situations, sufferings, and emotions are perishable, we realise that the only conquest useful to us is our own mind. The real and only worthwhile journey is into our selves and our soul, for our soul is our greatest guru. When we understand our own soul, we understand all souls. They are all one. The Power of Purity aims to familiarise us with the nuances of our lives and to remind us to steer away from the illusions that the world offers.

Here’s an excerpt from the book in which the author introduces us to a way of life that will help us become aware of ourselves and elevate our soul.

*

Bless all. It will make you serene and light. Blessing expands you. It makes you light. When we bless all the people we like and all the people we do not like, we truly become the perfect expression of the Almighty. His true expression is unconditional love. When we remove all hatred and fear from our mind, we become an embodiment of love. Love expands. Love makes our life enjoyable. When we express sincere gratitude to all the objects and beings that helped our existence on Earth, we become universal. Once we understand the true relevance of the food that we have consumed so far, the houses that sheltered us, the books that gave us knowledge, our parents and our teachers, and, above all, the element of divinity that sustained us, we will be filled with humility and deep gratitude. Most of our vital functions, including respiration, circulation, digestion, heartbeat and even sleep, for that matter, are controlled by our subconscious mind. All these things are working in perfect synchronization because our conscious mind has nothing to do with it. We are given the time, space, intellect and situation to act out our inherent traits. What do we have in our control? Why do we blame others? Why do we entertain guilt at all? What is there to be afraid of? All experiences have been lessons. We could not have changed anything. So what else can we do, except express unconditional love and compassion? What else can we do but bless everybody and everything? When we realize that we are not really the one who does everything, we will see our ego getting nullified and our doership getting dissolved. We will then operate in perfect awareness and gratitude.

God is within us. God is to be loved, not feared. The soul element that fuels our existence is the God within all of us. God, the one who generates, operates and dissolves. Hence, all of us possess the same god element. No one is inferior nor superior to anyone. Some evolved higher through rigorous practices, contemplation and meditation. Through lifetimes of efforts, they attained higher awareness. That’s all. In principle, all are one and the same. The same soul element fuels the existence of all living beings, which includes plants and animals. Just like the same electricity is used to operate various equipment, the same soul operates various bodies, and some of them are human.

All of us are temporary custodians of a body, of money and possessions. It is the same with relationships. Everything is temporary. Everything has a definite longevity. There is no room for egocentric expressions, if we digest this truth. All we can do is forgive everything. Bless everything.

**

To understand your consciousness, the meaning of life, and the various facets of existence, read Mohanji’s The Power of Purity.