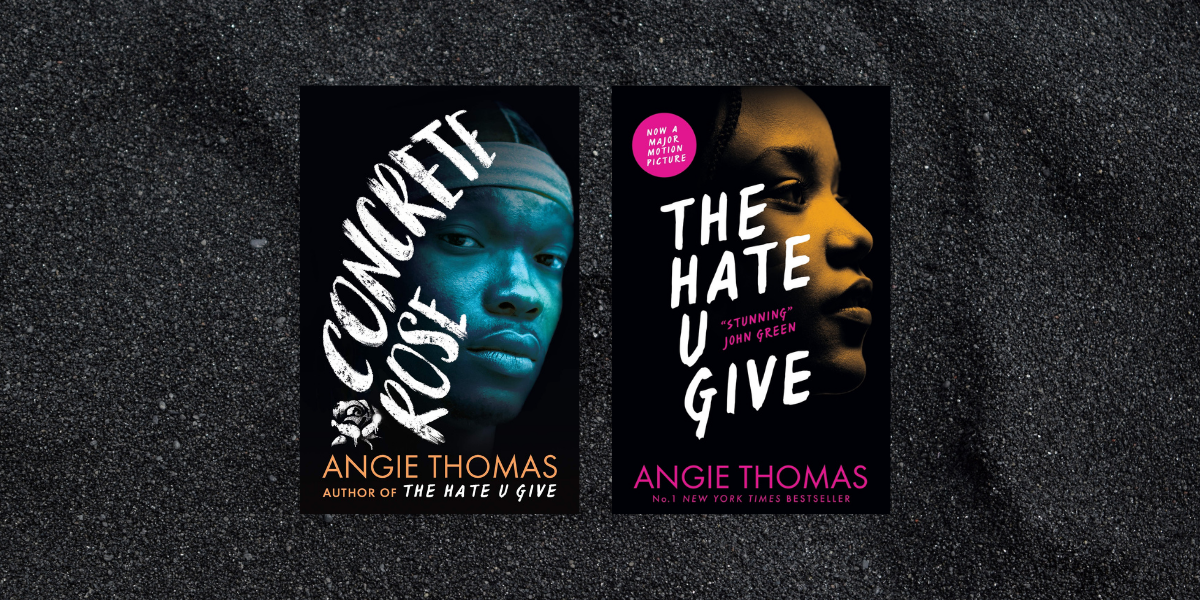

Angie Thomas’ new book Concrete Rose returns to the site of her previous work, The Hate u Give, where the narrative events are catalysed by the police shooting of an unarmed black teenager. We’re returning to Thomas’ books, which are inspiring and necessary, delving into conversations around race, friendship, activism, and giving us characters that are unforgettable. Here is an excerpt from The Hate u Give:

A commotion stirs in the middle of the dance floor.

Voices argue louder than the music. Cuss words fly left and right.

My first thought? Kenya walked up on Denasia like she promised. But the voices are deeper than theirs.

Pop! A shot rings out. I duck.

Pop! A second shot. The crowd stampedes toward the door, which leads to more cussing and fighting since it’s impossible for everybody to get out at once.

Khalil grabs my hand. “C’mon.”

There are way too many people and way too much curly hair for me to catch a glimpse of Kenya. “But Kenya—”

“Forget her, let’s go!”

He pulls me through the crowd, shoving people out our way and stepping on shoes. That alone could get us some bullets. I look for Kenya among the panicked faces, but still no sign of her. I don’t try to see who got shot or who did it. You can’t snitch if you don’t know anything.

Cars speed away outside, and people run into the night in any direction where shots aren’t firing off. Khalil leads me to a Chevy Impala parked under a dim streetlight. He pushes me in through the driver’s side, and I climb into the passenger seat. We screech off, leaving chaos in the rearview mirror.

“Always some shit,” he mumbles. “Can’t have a party without somebody getting shot.”

He sounds like my parents. That’s exactly why they don’t let me “go nowhere,” as Kenya puts it. At least not around Garden Heights.

–

© 2017 Angela Thomas, by permission of Walker Books Ltd.

~

Concrete Rose is a return to Garden Heights, seventeen years before the events depicted in The Hate U Give. It is a fierce and inspiring account of what it means to grow up as a black man in the United States. Here is an excerpt:

“That trifling heffa! And I don’t mean Iesha,” Ma says. “I mean her momma!”

Ma ain’t stopped fussing since we left the clinic.

At first I thought Iesha and Ms. Robinson stepped outside. Nah, they left. One of the nurses said she pointed out they were leaving the car seat. Ms. Robinson told her, “We don’t need it anymore,” and shoved Iesha out the door.

We went straight to their house. I banged on the doors, looked through the windows. Nobody answered. We had no choice but to bring li’l man home with us.

I climb our porch steps, carrying him in his car seat. He so caught up in the toys dangling from the handle that he don’t know his momma left him like he nothing.

Ma shove the front door open. “I had a funny feeling when I saw all them clothes in that diaper bag. They shipped him off without a word!”

I set the car seat on the coffee table. What the hell just hap- pened? For real, man. I suddenly got a whole human being in my care when I never even took care of a dog.

“What we do now, Ma?”

“We obviously have to keep him until we find out what Iesha and her momma are up to. This might be for the weekend, but as trifling as they are…” She close her eyes and hold her forehead. “Lord, I hope this girl hasn’t abandoned this baby.”

My heart drop to my kicks. “Abandoned him? What I’m supposed to–”

“You’re gonna do whatever you have to do, Maverick,” she says. “That’s what being a parent means. Your child is now your responsibility. You’ll be changing his diapers. You’ll be feeding him. You’ll be dealing with him in the middle of the night. You—”

Had my whole life turned upside down, and she don’t care.

That’s Ma for you. Granny say she came in the world ready for whatever. When things fall apart, she quick to grab the pieces and make something new outta them.

“Are you listening to me?” she asks.

I scratch my cornrows. “I hear you.”

“I said are you listening? There’s a difference.”

“I’m listening, Ma.”

“Good. They left enough diapers and formula to last the

weekend. I’ll call your aunt ’Nita, see if they have Andre- anna’s old crib. We can set it up in your room.”

“My room? He gon’ keep me awake!”

She set her hand on her hip. “Who else he’s supposed to keep awake?”

“Man,” I groan.

“Don’t ‘man’ me! You’re a father now. It’s not about you anymore.” Ma pick up the baby bag. “I’ll fix him a bottle. Can you keep an eye on him, or is that a problem?”

“I’ll watch him,” I mumble.

“Thank you.” She go to the kitchen. “‘He gon’ keep me awake.’ The nerve!”

I plop down on the couch. Li’l Man stare at me from the car seat. That’s what I’m gon’ call him for now, Li’l Man. King Jr. don’t feel right when he my son.

My son. Wild to think that one li’l condom breaking turned me into somebody’s father. I sigh. “Guess it’s you and me now, huh?”

I hold my hand toward him, and he grip my finger. He small to be so strong. “Gah-lee,” I laugh. “You gon’ break my finger.”

He try to put it in his mouth, but I don’t let him. My fingernails dirty as hell. That only make him whine.

“Ay, ay, chill.” I unstrap him and lift him out. He way heavier than he look. I try to rest him in my arms and sup- port his neck like Ma told me to. He whimper and squirm till suddenly he wailing. “Ma!”

She come back with the bottle. “What, Maverick?”

“I can’t hold him right.”

She adjust him in my arms. “You relax, and he’ll relax.

Now here, give him the bottle.” She hand it to me, and I put it in his mouth. “Lower it a little bit, Maverick. You don’t wanna feed him fast. There you go. When he’s halfway through it, burp him. Burp him again when he’s done.”

“How?”

“Hold him against your shoulder and pat his back.”

Hold him right, lower the bottle, burp him. “Ma, I can’t—” “Yes, you can. In fact, you’re doing it now.”

~

Two beautiful, urgent reads that will stay with you.