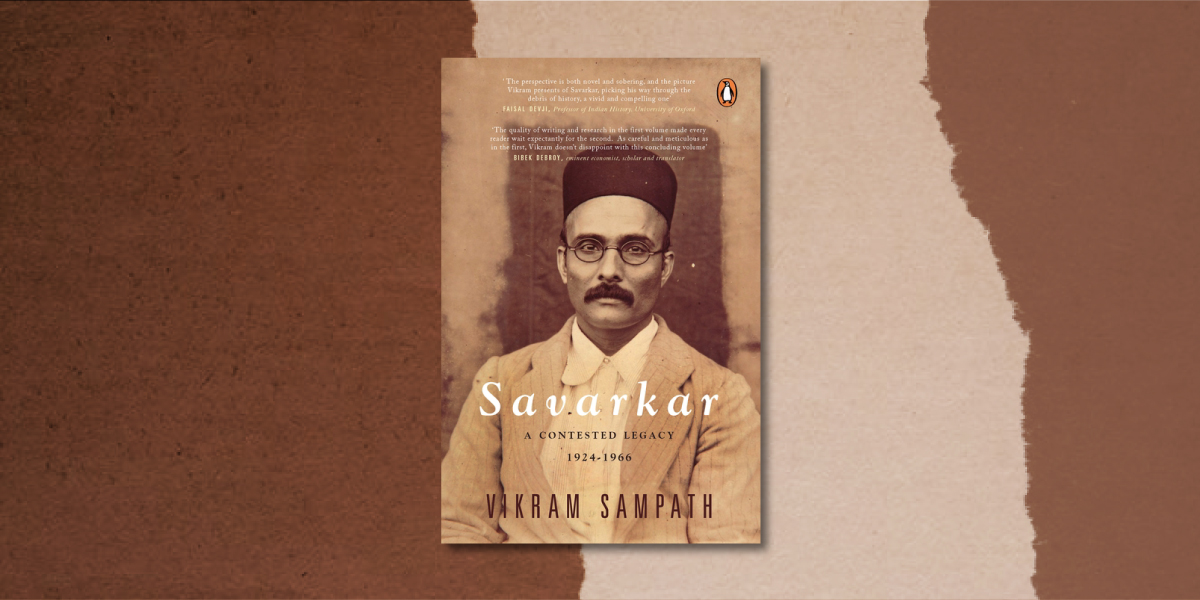

After the success of the first part, Vikram Sampath now unveils the concluding volume of the Savarkar series, the exploration of the life and works of one of the most contentious political thinkers and leaders of the twentieth century, Vinayak Damodar Savarkar.

Here is an exclusive and intriguing excerpt from the book where the author talks about Savarkar’s scepticism towards Nehru’s policy towards China and other matters of international relations:

With the restrictions on his political activities ceasing, Savarkar began to be more vocal on various aspects of national and foreign policy and governance. He was particularly sceptical and critical of Nehru’s policy towards China. On 29 April 1954, India signed the Panchsheel or the Five Principles of Peaceful Coexistence with China. Four years earlier, China had invaded and occupied Tibet and India had remained silent. Writing about these in the Kesari on 26 January 1954, Savarkar said:

When China, without even consulting India, invaded the buffer state of Tibet, India should at once have protested and demanded the fulfilment of rights and privileges as per her agreements and pacts entered into with Tibet. But our Indian Government was not able to do any such thing. We closed our eyes in the name of world peace and co-existence and did not even raise a finger against this invasion of Tibet. Neither did we help this buffer state of Tibet when her very existence was at stake. Why? The only reason that I visualize is our unpreparedness for such an eventuality and/or war . . . That is the reason why after swallowing the whole of Tibet the strong armies of China and Russia are now standing right on our borders in a state of complete preparedness and on the strength of the above, China is today openly playing the game of liquidating the remaining buffer states of Nepal and Bhutan . . . We have not been able to put before her an army which can match the strength of her armies on these borders of ours even today. This is precisely the reason why China dares come forward with such an unabashed claim on our territories . . . China completely overran Tibet and destroyed the only buffer state so as to strengthen her vast borders. By this act of hers, China had with one stroke come right on our borders by force and prepared the way for an open aggression against India whenever she felt like it. Britain, when she was ruling over India, had by careful planning, pacts, treaties and agreements created a chain of buffer states like Tibet, Nepal and Bhutan in order to strengthen the borders of India and to safeguard it from China and Russia. Afghanistan also acted like a buffer state on the other side. Britain had on behalf of the Government of India, directly or indirectly taken upon herself by various pacts, charters and agreements even the guarantee of continued existence of these buffer states. Immediately on attainment of independence all these rights were transferred to the independent sovereign Republic of India. But in the very six years that we criminally wasted, China has equipped her whole nation with most modern and up-to-date arms, and without in the least caring for the feelings and sentiments of India had completely overrun Tibet and destroyed the only buffer state so as to strengthen her vast borders. 15

Savarkar asked India to emulate the example of Israel that came into existence in May 1948 after almost a two-thousand-year struggle by the Jews for a homeland of their own. Israel, he said, ‘is besieged by their staunch enemies Arab nations. But this tiny nation has given military education to its men and women, procured weapons from Britain and U.S.A., established arm [sic] factories in their own nation, intelligently signed treaties and with foreign nations and raised its own strategic power to that extent that their enemy Arab nations would never dare to invade them.’ 16

He claimed that it was still not too late for India to wake up from its slumber and similarly increase her military and strategic strength as the world recognizes only that. The Chinese prime minister Zhou Enlai was accorded a warm welcome in New Delhi on 26 June 1954 and Nehru coined his favourite phrase ‘Hindi Chini Bhai Bhai’. In an interview on this India–China diplomacy in the Kesari on 4 July 1954, Savarkar welcomed this bonhomie with a sense of cautious optimism. He said:

‘In politics the enemy of our enemy is our best friend. Enlightened self-interest is the only touchstone on which friendship in political dealings could be tested, since there is no such thing as real and selfless friendship in the political arena. If the meeting between Chou En-Lai and Nehru angered the U.S.A., Indians should not pay attention to it because the U.S.A. too did not care to pause and think about India’s sensitivities if America entered into a military pact with Pakistan. All the policies of

India must be dependent on what was good or bad for India herself. If it was advantageous to India she should not in the least worry or care whether anyone felt enraged, insulted or irritated . . . The general principles that are being propagated as fundamental in this visit are very good and sound, so far as their language is concerned. Nothing is lost in proclaiming wishes for world peace, prosperity and brotherhood. But so long as India does not have any effective practical remedy or measures to check the transgressions, such visits have no more than a formal status. While crying from the roof tops about these principles it was worth noting that China, by swallowing Tibet, had ruthlessly trampled those very principles of world peace, brotherhood and peaceful co-existence. That was the funniest part of the whole deal, and it at once raised doubts in Indian minds about the bona fides of China and Chou En-Lai. There was at that time a political party in Tibet aiming at independence.

It was curious and in a way most astonishing that after preying on and swallowing the mouse of Tibet the Chinese cat was talking of going on a pilgrimage. That was exactly the role that the Chinese Premier Chou En-Lai and President Mao Tse-tung were playing. 17

In the same piece Savarkar also emphasized on the fundamental theory of foreign policy, which was permanent national interests and not merely high-sounding, one-sided moral principles. He hoped that the Panchsheel did not run this risk.

He said:

China, Russia, Britain and even the recently established Pakistan all are talking of high-sounding principles, but they do so as a step towards diplomatic measures to achieve their own ends, and for the success of their own political objectives. In the present state of human relationship it should be just so; but of all the countries India alone has for long been in the habit of preaching sermons of high principles to others and unilaterally bringing them into practice, which ultimately proves disastrous to the interests of India. I only hope that this does not happen in this case of the Panchsheel. What I feel is that if at all China uses India as a springboard to push forward her own territorial aims and interests, India should also primarily safeguard her own interests and if these moves do not go against her interests then alone take part in it. So long as China is looking to further her interests alone, India should also follow the same and use the good wishes of China only in so far as they help to push the interests of India forward. We should believe in their good faith and good intentions as much as and as long as they believe in ours. One fact must be made clear here and it is that [the] U.K., U.S.A., U.S.S.R. and China can force India to bring into practice all these principles because they hold the upper hand, being in possession of atomic and nuclear weapons of warfare. But can India do the same? Can India force these nations to see that they follow the principles that they profess to preach? This is the most important question. It is no use having political or diplomatic friendship alone with either China or Russia. We must immediately undertake to see that military potential and preparedness of the Indian armed forces with modern and most upto-date weapons of warfare is not being neglected and that we too can produce atomic and nuclear weapons just as these nations can. If China can erect plants and factories for the manufacture of atomic weapons of warfare in Sinkiang and other places we should also be able to do so. There is nothing difficult in it. Our scientists and laboratories might be able to invent and manufacture such weapons in a year or two or they might invent even more destructive ones . . . But so long a weak and impotent Government at the Centre does not take even one step to achieve these objectives it is no use talking of high principles and running after the mirage of world peace, peaceful co-existence, world brotherhood and prosperity, and nothing good can come out of such so-called good-will visits. High principles must have a robust armed strength behind them to see that they are brought into practice by those who wax eloquent about it. Taking all these things into consideration I feel that the time has come now when the Central Government must immediately take steps to increase the armed might and the military potential of India. 18

A lot of what Savarkar wrote about and cautioned was to turn prophetically true in the decades to come as far as India’s strategic, military and foreign relations were concerned.

*

Read Vikram Sampath’s Savarkar (Part 2) A Contested Legacy, 1924-1966 to know more about the opinions and works of Savarkar.