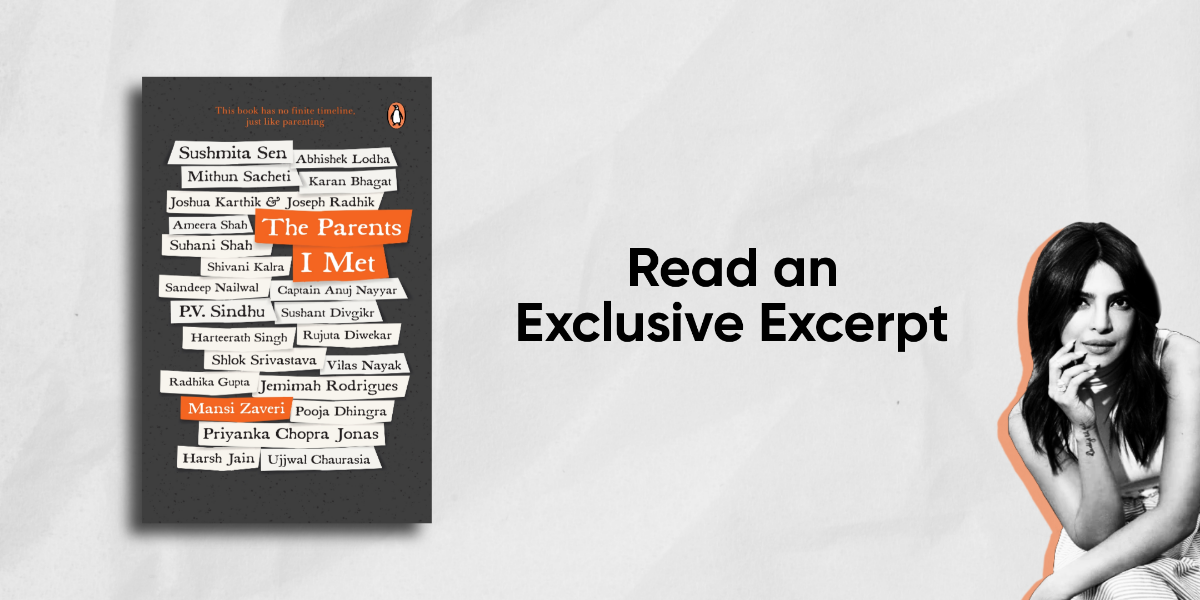

Ever wondered, “Am I getting this parenting gig right?” In Mansi Zaveri’s The Parents I Met, take a stroll through chats with successful parents, picking up timeless tips for navigating the tricky path of raising kids. This book is like a friendly guide, saying, “Hey, in the middle of life’s chaos, what matters most is your love and commitment to your kids.” It’s an easy read, full of stories and advice that any parent can relate to, giving you a bit of comfort and a lot of insights along the way.

***

Initially, I had arranged to speak with Dr Madhu Chopra via Zoom, but after our conversation, I knew I had to meet her in person. She never made her career, marriage or the proper upbringing of her children a lower priority simply because she became a mother.

Despite her initial doubts about whether her parenting practices from nearly three decades ago would still be relevant, she welcomed me with open arms and was happy to talk. Friendly as always, she paused to ask her assistant Zarin for a green tea in Gujarati, all the while considering which chai flavour would best prepare her for this exchange. She then took a sip and said,

‘Mansi, what was important is that I didn’t back down—that gave me immense confidence. That confidence emanates power and brings me respect from my kids even to this day. If they respect you, it becomes easy.’

She has fond memories of working night shifts at the army hospital, which were always a family affair because she had to bring her two children along, Priyanka and her brother Siddharth. ‘I turned it into a game by telling Priyanka, “Mom’s on night duty, baby’s on night duty,” as she carried her toy backpack and squealed with excitement. I didn’t fall into the trap of feeling guilty because my work gave me immense joy. The guilt crept in only once when she talked back to my father and that made me wonder, “Is it because I am working?” Even the fancy well-planned tiffins of other kids who had stay-at-home moms couldn’t make me feel guilty as I sent the same tiffins every day, like a paratha roll or jam sandwich. I taught her to not compare these tiffins or feel deprived. Parenting is not a day’s job. It starts the day your baby is conceived and continues forever.’

I asked her if Priyanka had ever asked, ‘Why can’t you sit at home or why do you need to work?’ and she said, ‘No. She didn’t know any other way and took this as normal.’ Family was a huge support, with both sets of parents and relatives chipping in at every stage.

Dr Chopra continued, ‘Both kids used to tag along. If mom had night duty, baby had night duty. She would pack her little bag to carry to the hospital because she knew she had to keep herself busy while I was away on duty. You see, we didn’t give them choices that didn’t exist.’

Dr Chopra then unapologetically admitted, ‘I am a great parent.’ To see a parent be so self-assured was refreshing. Especially when parents today second guess most of their decisions.

When Priyanka was preparing for Miss India, her entire family pooled their resources to buy her new footwear, wardrobe and cosmetics. No one ever questioned who she was or why she would want to compete in a Miss India pageant. Some parents hope their children will follow in their footsteps and go into business with them or pursue a similar line of work, but Priyanka knew at the tender age of three that she did not want to become a doctor because she did not like the smell of hospitals and did not want to leave her child at home.’

She added, ‘When your path is different from your kids, there is no tantrum and shouting but there is a conversation. You convince me or I convince you.’ The one time that we did push our wishes on a child who was a topper in her academics and extracurriculars, was when we asked her to sing and dance both. When her grades dipped, I backed off, but being a committed, competitive learner, she persevered. Her habit of seeking perfection in everything that she did was most evident when she helped her younger brother Siddharth learn his speech on Chacha Nehru. She corrected his work and sat all night rehearsing with him till he didn’t even miss a single word.’

She continued, ‘I think this is the temperament that has got her here and is keeping her here. Ours was a democratic house, and questions and curiosity were rewarded promptly. When Priyanka was in kindergarten and questioned why her name was missing from the name plate outside her house, her father, Dr Ashok Chopra, got it changed the next day and added “Priyanka Chopra-UKG”.’

Dr Chopra went on to say, ‘Dinner table conversations were animated ones, where you could pour your heart out and no one would be judged. No one raised their voices or banged plates—it was not allowed in my household. Our kids never saw us yell, fight or be violent—it started and ended in the bedroom, but even that was a discussion.’

‘I was heartbroken when I sent her to boarding school at seven years old after she had talked back to my dad,’ she confessed, ‘but the end result of that decision was a polished, responsible pre-teen who could even parent me. She became so disciplined, much better than I could have ever done. Each leap of faith was made with my family as a safety net.’

When I asked her if she had had any indication that Priyanka was exceptional before she turned eighteen, she said, ‘I knew my child was focused and never frivolous. She would make the most of every opportunity that was presented to her. You cannot be a great parent if you don’t have a receptive child.’

When I asked her how she managed to instil such a sense of hunger and determination in her children despite their privileged upbringing, she told me that teaching them to say ‘no’ was crucial, as was making them work for what they want.

She said, ‘Don’t be afraid to be that “bad parent”. The word “no” carried great weight in the Chopra household. One parent’s “no” would never be followed by a “yes” from the other. Their “whys”, however, were never shunned but addressed with discussions and explanations of the consequences early on. My children knew from day one that their every action had a consequence and that would be theirs alone.’

***

Intrigued to know more?

Get your copy of The Parents I Met by Mansi Zaveri wherever books are sold.