There is a close symbiotic relationship between Hinduism and Nature. The basis of Hindu culture is dharma or righteousness, incorporating duty, cosmic law and justice. Every person must act for the general welfare of the earth, humanity, all creation and all aspects of life. Dharma is meant for the well-being of all living creatures. The verses of the Vedas express a deep sense of communion of man with god. Nature is a friend, revered as a mother, obeyed as a father and nurtured as a beloved child. In Vedic literature, all of nature was, in some way, divine, part of an indivisible life force uniting the world of humans, animals and plants.

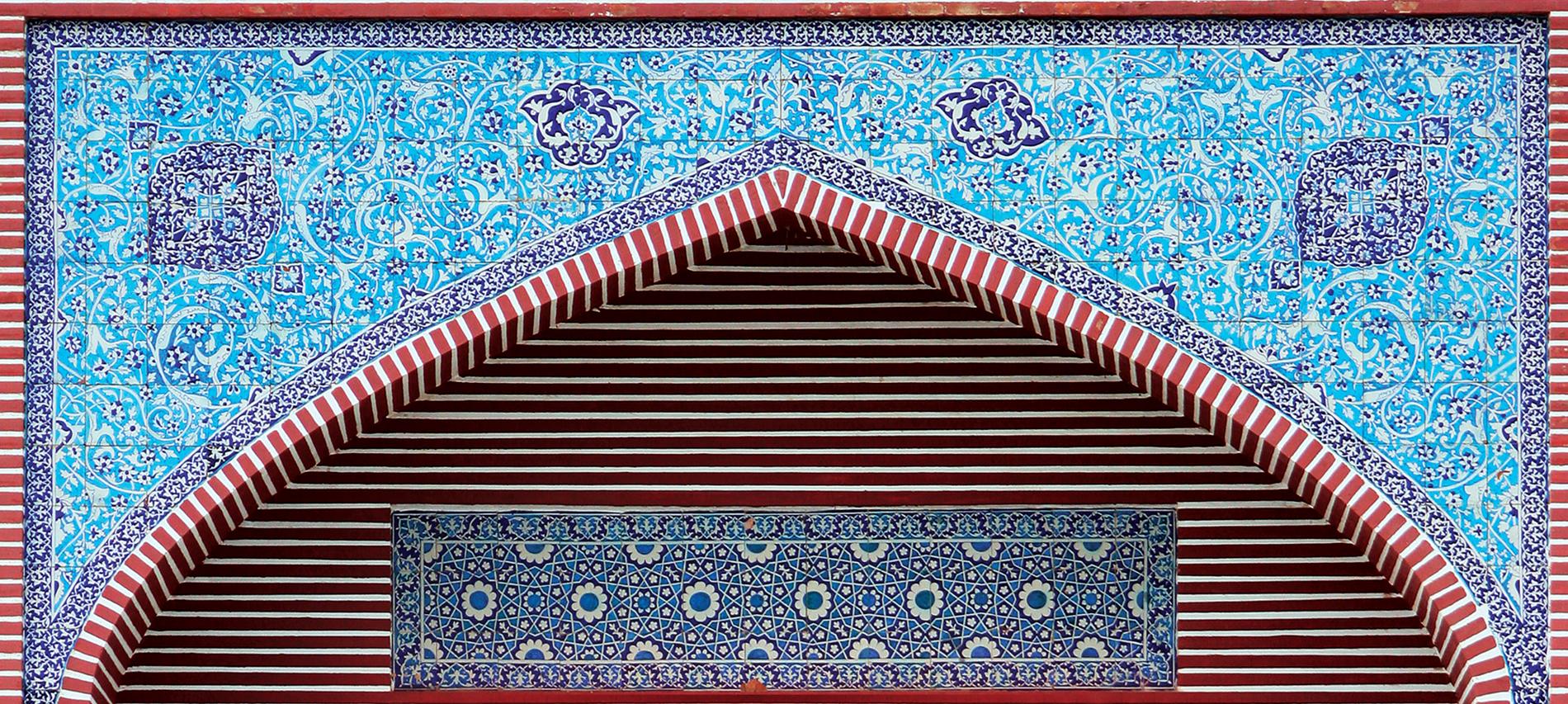

Five thousand years ago, the Vedic sages showed a clear appreciation of the natural world and its ecology. There is a hymn to the rivers (Nadistuti Sukta) in the Rig Veda and a hymn to the earth (Prithvi Sukta) in the Atharva Veda. Throughout the Vedas there is a deep respect for life which is an important manifestation and expression of the gods. The need to protect and conserve biological diversity is exemplified in the representation of Shiva, Parvati, their two sons Karttikeya and Ganesha and their vahanas or vehicles – bull, lion, peacock and mouse respectively – who live in close harmony.

There is a very strong and intimate relationship between the biophysical ecosystem and economic institutions which are held together by cultural relations. Hinduism has a definite code of environmental ethics and humans may not consider themselves above nature, nor can they claim to rule over other forms of life. Every aspect of nature is sacred for the Indic religions: forests and groves, gardens, rivers and other waterbodies, plants and seeds, animals, mountains and pilgrimage centres. The sacred is still visible in modern India. All creation is a manifestation of the divine with no dichotomy between humanity and divinity. Religious practices are influenced by local environmental and festivals coincide with a natural phenomenon.

I fell in love with sacred groves attached to Hindu temples, where not a twig may be broken and which are the remnants of ancient forests where sages lived in harmony with nature; with rivers that gush from the hills and meander through the land; with the sacred tanks attached to each temple, the sacred plants and the animals respected by my religion; with the awe-inspiring mountains which reach up to the skies and where the Gods live. Every festival reminds us of the importance of nature in our lives. As the author of Sacred Plants of India and Sacred Animals of India I explored the divine relationship between human beings, plants and animals, which are an essential part of every Hindu prayer.

“The Earth is my mother and I am her child,” says the hymn to the Earth in the Atharva Veda. The human ability to merge with nature was the measure of cultural evolution. Hinduism believes that the earth and all life forms – human, animal and plant – are a part of Divinity, each dependant on the other for sustenance and survival. All of nature must be treated with reverence and respect. If the forests, clean water and fresh air disappear, so will all life as we know it on earth.

——————————————————

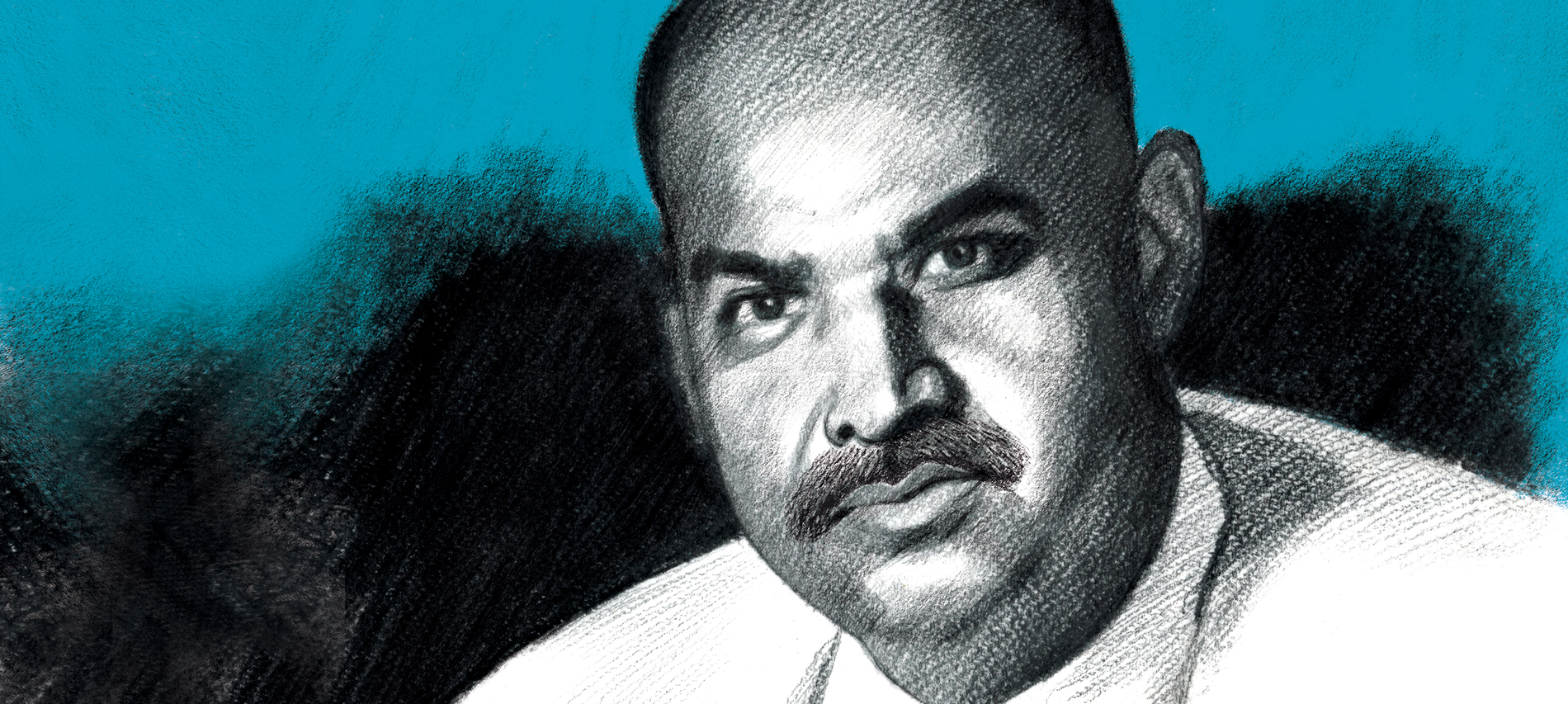

A historian, environmentalist and writer based in Chennai, Nanditha Krishna has a PhD in Ancient Indian Culture from Bombay University. She has been a professor and research guide for the PhD programme of C.P.R. Institute of Indological Research, affiliated to the University of Madras. Her latest book, Hinduism and Nature delves into the religion’s deep respect for all life forms, the forests and trees, rivers and lakes, animals and mountains, which are all manifestations of divinity.

Sources:

Sources:

To know how modern India came into existence, you must pick a copy of Creation of Wealth!

To know how modern India came into existence, you must pick a copy of Creation of Wealth!