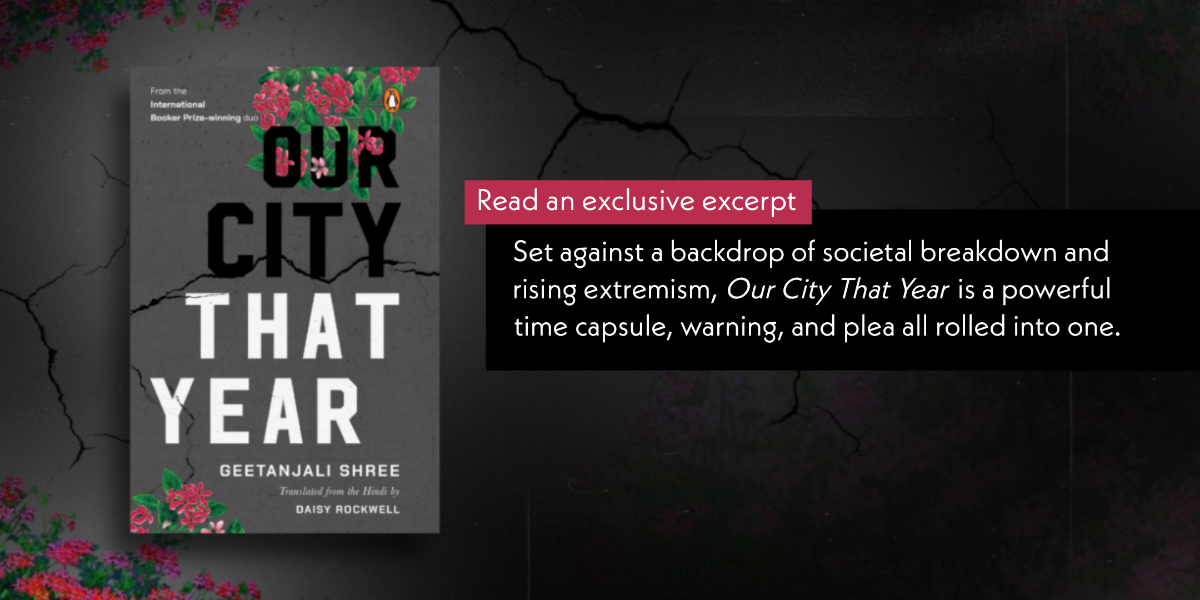

Our City That Year by Geetanjali Shree takes you into a city torn apart by faith and conflict, where chaos and violence are everywhere. Through the eyes of a writer and others caught in the middle, the story shows how people try to understand what’s happening around them. With Daisy Rockwell’s brilliant translation, this novel will stay with you long after you finish.

Read this excerpt to get a glimpse of a city on the edge and those trying to survive it.

***

That year, in our city, Hindus abandoned their pacifism. We’ve run out of other cheeks to turn, they proclaimed. We’re helpless! they screamed. They climbed atop mosques and waved the flag of Devi affixed to their tridents proclaiming, What was done to us will be visited on them! Wrong shall be answered with wrong! Holy men abandoned their meditations, and angry cries echoed in place of prayers: They killed our progeny, dishonoured our daughters! Sons, are you cowards or men? O, descendants of the heroes Shivaji, Bhagat Singh, Rana Pratap; O, sons of Arjun and Bhima, rise! Transform the neighbourhoods of your enemies into graveyards! Enough with your gentlemanly behaviour! Even the deities rage when the crimes of demons are on the rise.

Arise.

Awake.

Save us.

And out poured gangs upon gangs to tear the mosques in our city down to their foundations and erect the idols of goddesses and gods in their place. The air in our city began to pulse. It echoed with their feelings of helplessness: boom boom. The gangs emerged with a clamour, raising clouds of ash which could turn to dust at any time and sting our eyes. They released fountains of Ganga water which could turn to blood at any time and splatter our eyes. It was like a rollicking festival. So many hues, it could have been Holi in a storm of coloured powder. They held sacrifices and threw into the flames the cowardice that had been nurtured in the name of dispassion. They marked their brows with a tilak of ashes, hurled sharp bits of metal at the sun, slicing it to ribbons, skewering the brilliant sun-scraps and waving them in the air as they fanned out into the streets, over the moon to discover in their clutches the joyous sun. We shivered when we saw how the sun danced in their hands.

* * *

‘Should I write from the perspective of a child?’ Shruti asks. Her hands drip red from peeling beets. ‘Of our unborn child? Who will see this, hear this, tell this?’

‘No,’ Hanif vetoes the idea at the outset. ‘For one,’ he says, ‘that narrative style is very old, it’s been going on since the time of the Mahabharata. For another . . .’ his voice is severe now, ‘we don’t even want a child. Who would want to inherit these times?’

Even the glancing thought of an unborn child’s testimony fills me with dread. But why?

If I just shadow them and keep copying, what do I have to fear.

* * *

‘Why should we be afraid? We live over here. Your friend has no right to spread the psychosis of fear. He enjoys it even,’ frets Shruti.

They sit in the flat upstairs. Dirty dishes piled before them. Sharad has just gone home, downstairs. Earlier, the three of them had been eating, drinking, gossiping, and I’d been standing nearby, wondering if I should listen, if I should copy everything down, if I should just ignore. The three diners had pushed bay leaves, cloves, cinnamon sticks, black cardamom pods to one side on their plates. Sharad’s final utterance still lingers in the air: ‘The city’s on fire, and you’re laughing?’

That’s where I’ll start, I resolve; that’s where I’ll begin to record.

‘You’re humourless.’ Hanif ribs Shruti. ‘Sharad was teasing you because he knows you’ll blow up.’

‘That wasn’t teasing at all. Your friend is the completely humourless son of an overly humourful father.’ Shruti was angry when she started to speak, but by the end she smiles at her own mention of Daddu.

‘But the fire’s been lit.’

‘But not here, over there,’ Shruti objects.

‘But the fire can’t burn us. Sati is still in practice, tenderhearted women watch as their own kind are set aflame, fingers burn daily turning chapatis on hearths: fire is our familiar! Why should we fear it burning us?’

‘Arre, are you waxing philosophical or just telling tasteless jokes like your friend?’

* * *

I am not omniscient. I write about wherever I am, whenever. I cannot weave things together. I wouldn’t know a warp from a woof. But I cannot escape writing. Will any witness survive this horrifying tongue that flickers about devouring our city? Because, who knows, tomorrow this tongue could find us . . . and you? And if we are no more . . .

And who knows if by some simple coincidence we survive, or you survive, then perhaps we’ll be able to understand something when we look back. Or preserve something.

But now, just write. Write without comprehension. And if not you, then I will write down whatever you say, write, see; whatever can be expressed in ink.

* * *

Get your copy of Our City That Year by Geetanjali Shree on Amazon or wherever books are sold.