The English Maharani by Miles Taylor charts the remarkable effects India had on Queen Victoria as well as the pivotal role she played in India. Drawing on official papers and an abundance of poems, songs, diaries and photographs, Taylor challenges the notion that Victoria enjoyed only ceremonial power and that India’s loyalty to her was without popular support. On the contrary, the rule of the queen-empress penetrated deep into Indian life and contributed significantly to the country’s modernisation, both political and economic.

As the world commemorates Queen Victoria’s bicentenary today, here’s an excerpt from the book:

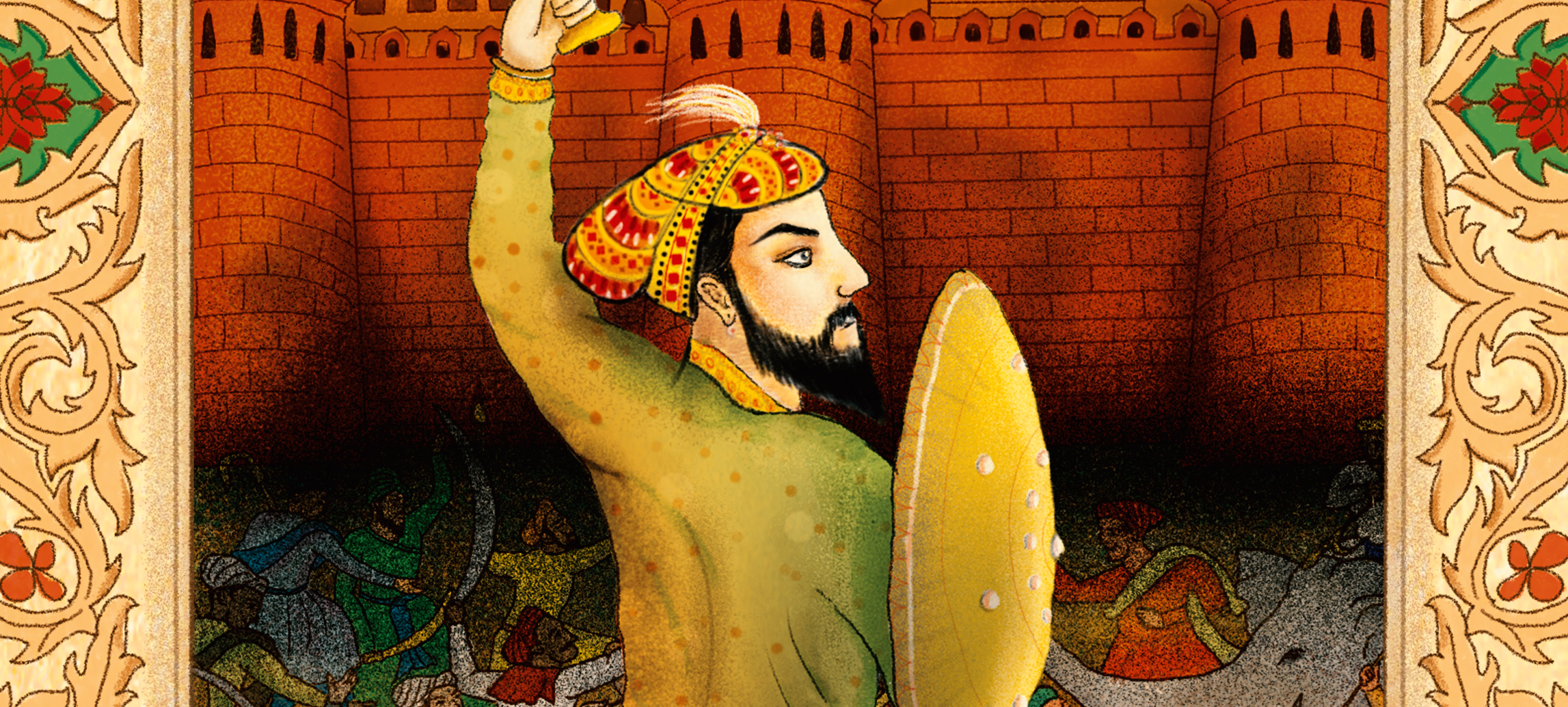

Victoria and Albert collected Indian exhibits of their own in the early 1850s, in the form of adopted royal children. There were two: Princess Gouramma, daughter of Chikka Virarajendra, the Raja of Coorg (Kodagu), and the Maharaja Duleep Singh, who been taken into custody by the British in 1849. Queen Victoria was godmother to many infants, including the African American Sara Bonetta in 1851, and, from New Zealand, the son of a Maori chief, who was baptised Albert Victor Pomare at Buckingham Palace in 1863. Her Indian adopted children received special treatment. Both were welcomed almost as new siblings, their acceptance into the royal home marked by rituals of conversion and depiction. Princess Gouramma arrived at the court via the Basel mission in Mysore. Persuaded by the mission, the Raja of Coorg negotiated with the East India Company to have his daughter, then aged eleven, brought up in England, under the guardianship of the queen. In exchange he hoped for the return of his wealth, seized by the British in 1834. He had already used his children as bargaining chips. Another daughter had married Jung Bahadur, the chief minister of Nepal in 1850. Gouramma was brought over from India by Mrs Drummond, the wife of a retired major in the Bengal cavalry, and came to Buckingham Palace at the beginning of June. As the terms were agreed about her adoption, the queen showed off Gouramma to her own children, and commissioned Franz Winterhalter to paint her portrait. The queen watched the sitting and made her own sketches of the Indian princess. Gouramma also played with the royal children. At the end of the month she was christened in the chapel of Buckingham Palace. The Archbishop of Canterbury performed the service, Lord Hardinge and James Hogg (of the East India Company) were Gouramma’s sponsors and, with all the royal family in attendance, the queen led Gouramma to the font, naming her Victoria. Controversy flared after the baptism, when her father objected that Gouramma’s guardian, Mrs Drummond, was not of sufficiently high social standing and claimed that he had been misled into the wardship of his daughter. As a compromise Gouramma remained looked after by Mrs Drummond but at the homes of various families with connections to the Government of India, such as the Hoggs, the Hardinges and the Woods. Her father’s grudge against his treatment by the Company continued until his death in 1859, whilst Gouramma eventually married a lieutenant colonel, John Campbell, and with him she had a daughter of her own, Edith.Queen Victoria celebrated the little princess Gouramma as a Christian convert from the east. Winterhalter’s portrait shows Gouramma in her Indian clothes: a fitted blouse, pleated sari with a wide embroidered pallu, gathered by a gold belt. She is heavily jewelled with an elaborate headpiece. In her hand she holds a small Bible. The queen also commissioned the sculptor Carlo Marochetti to capture the moment of Gouramma receiving her crucifix, executed in pale marble. The queen then had the bust painted to enhance Gouramma’s facial features. An almost identical pattern was repeated with Duleep Singh. He arrived at Buckingham Palace two years after Gouramma, in the summer of 1854. As an eight- year- old boy, Duleep Singh had been taken into the care of the British forces under Henry Hardinge, who pitied the plight of the ‘beautiful boy’. Dalhousie was far less sympathetic to Duleep Singh, ‘a brat begotten of a bhistu – and no more the son of old Ranjeet than Queen Victoria’. Nonetheless after the surrender of the Punjab in 1849 Dalhousie authorised the boy to be placed into the guardianship of Sir John Login, former surgeon at the British residency in Lucknow, and his wife, Lena. As temporary governor of the citadel at Lahore, Login was in charge of the dispersal of the Lahore treasury. Duleep Singh proved one piece of booty over which he was especially careful. Whilst his mother was exiled to Kathmandu, the young maharaja was taken to Fatehgarh for his safety, and there began his western education with the Logins, converting to Christianity in 1853. The switch of faith surprised many, including Dalhousie. In the meantime, arrangements were made for what portion of the Lahore treasury would be kept for the prince, for the costs of his maintenance in England, with some set aside for the construction of a tomb for Ranjit Singh at Amritsar. By the time Duleep Singh arrived in London, he was a well- groomed fifteen- year- old, with good English and refined manners, as the queen noted. Just as she had with Gouramma, she sat and watched Winterhalter paint Duleep on successive days, as well as sketching him when he joined the family at Osborne. Winterhalter’s portrait is a grandiose full- length study, depicting Duleep as a proud Sikh ruler, richly dressed, adorned with pearls, a sheathed sword in his right hand, and a temple in the background. One small detail hints at his conversion. Around his neck is a miniature portrait of Queen Victoria, the very same one that had been given to Ranjit Singh by Lord Auckland in 1839. Two years later, as she had done with Gouramma, Queen Victoria commissioned a bust from Marochetti of Duleep, and had it coloured, although was disappointed with the result. As well as sketching Duleep Singh, the queen kept a record of their conversations that summer. She went over the details of the narrative of his life, getting him to confirm some of the awful events – in particular, the murder of his uncle, Sher Singh, astride an elephant while Duleep was his passenger – and she questioned him about his conversion to Christianity and the ostracisation he had suffered from his family as a result. In an ironic twist she revealed to Duleep Singh some of her own souvenirs of the Punjab. She showed him Charles Hardinge’s sketches of him as a small boy, and let him see the Koh- i-Noor, which he was allowed to stroke. But she ensured that he did not view the captured Sikh arms on the terrace. Her fondness for Duleep was clear, but there was also a certain wallowing in his submissiveness. Passing on her congratulations for his sixteenth birthday she noted he ‘would have come of age, had we not been obliged to take the Punjab’.Duleep Singh returned to stay with the royal family at Windsor and Osborne again over the next two years, and on each occasion the queen was able to observe the progress of his education under the guidance of the Logins. Some of this took a conventional form. There was a lot of hunting and shooting in the Scottish Highlands, and a tour to Europe at the end of 1858. Other episodes in the grooming of the maharaja reflected Prince Albert’s enthusiasms. He was taken on a tour of the sites of Staffordshire in March 1856, including a descent down a pitshaft, and later that year attended the Birmingham cattle show and helped set up a refuge home for Indian lascars. He joined a volunteers regiment in 1859, and once he left London in 1859 to live at Mulgrave House, near Whitby, he represented the queen at various local functions. By the time he was a young adult, Duleep Singh was pining for the Punjab. To the consternation of Queen Victoria, he remained close to his mother. Duleep yearned to return to India, and finally travelled there in 1861, bringing his mother back with him to England, only for her to die two years later. He made another trip to India to scatter her ashes, and passing through Cairo on his return he met and married Bamba Müller, a young woman of German and Abyssinian descent who lived in the American mission there. They settled down to country life on a Norfolk estate, raising a family of six children, the first of whom, Victor Albert Duleep Singh, born in 1866, became the queen’s latest godson. Duleep Singh’s frustrations in forced exile in England radicalised him, and by the 1880s he was planning to renounce his Christianity, return to India and claim his succession as Sikh leader. He sought allies for his restitution as far as Cairo and Moscow, and finally died in Paris in 1893, separated from his homeland and from his family. For much of his life Duleep Singh proved a headache for the British government at home and in India, and on occasion he was a major strategic risk. Despite his reputation as a pampered prince, he remained a credible focal point for Sikh nationalism throughout his lifetime. For all his justifiable resentment against the British, Duleep Singh was considered an intimate member of the queen’s extended royal family until his death. From the marriage of Princess Vicky in 1858 through to the funeral of Prince Leopold in 1884, he attended every major royal ceremony, including the funeral of Prince Albert in 1861 and the thanksgiving for the recovery of the health of the Prince of Wales in 1871. On each occasion he sat on one side of the queen (her own children were on the other) along with the other foreign princes, mostly those from the smaller German states who were related to Victoria and Albert. Queen Victoria’s own dedication to Duleep rarely wavered. She defended him from suspicion that his loyalties lay elsewhere during the Indian rebellion of 1857–8. In 1868 she pressed Disraeli’s government to make further provision for Duleep Singh’s growing family, although that had not been part of the original terms under which he was included in the civil list (the public funds used to finance the royal family). Even in 1886, once his machinations with Russia were known, and she conceded that he was ‘off his head’, she still insisted that the government look after his family properly, in the event of his not returning to Britain. There was a final meeting between the queen and the maharaja in Grasse in the south -east of France in March 1891, two years before he died. Queen Victoria’s obsession with these two young exiles in the mid-1850s defies simple explanation. She undoubtedly had a genuine sympathy for the Indian royals whom her own government had done so much to displace. It extended to the old as well as the young. The same year that Duleep Singh came to the court, she had an audience with Prince Ghulam Mohammed, the last living son of Tipu Sultan, who had come to London to argue the case for ongoing support for his own sons and any descendants they might have. To support his claims Prince Ghulam republished the history of Tipu, already reasonably well known. The queen noted in her journal her respect for Prince Ghulam’s quiet dignity as he went about his appeals, whilst observing that had Tipu survived then all might have turned out very differently. Her magnanimity always came from belonging to the winning side. There was also a strong element of mothering. Tipu was widely depicted as a neglectful father. Queen Victoria’s wrath against Duleep’s mother and also her contempt for the Raja of Coorg betrayed the same indignation over poor parenting, the very reversal of the patriarchal household that she and Albert had developed around their own children. Her own maternal instinct was more than matched by Prince Albert’s vision of a princely confederation that might include his own sons, as well as the minor German princes and Duleep Singh. They were of royal blood after all. After his death, Victoria remained loyal to Albert’s dynastic aspirations, with her inclusion of all the princes in all the family ceremonies thereafter. Particularly in the case of Duleep, there was also a heavily romanticized appreciation of Sikhs and Sikhism, fuelled by the first- hand accounts from the battlefield and also by travel literature popularised by various German and English writers in the 1840s. As a war- like but conquered people, there was not a little vanity and conceit contained in the way in which the royal family not only captured Duleep in his Sikh finery, but also appropriated it for themselves. Most telling of all, the addition of these young India royals to the court represented the high- water mark of Queen Victoria’s evangelical aspirations for India. This can be seen in the rituals around conversion, that is to say, Gouramma’s baptism at the Palace, and Duleep being made to recount the trials he suffered surrounding his own conversion. It is also evidenced in the portraits and busts that the queen commissioned of the two, depictions emphasising their racial difference, whilst at the same time detailing the tokens of their new allegiance to a western monarch and to a Christian god. Here was Christianity in India making rapid strides at her very feet. Three days after she introduced Gouramma and Duleep Singh to each other for the first time, she wrote to Lord Dalhousie, saying how she approved of their future marriage (it never happened), and also how she hoped that the growing network of railways in India would ‘facilitate the spread of Christianity which has hitherto made very slow progress’. The Bible and the steam engine –religion and industry: for all their curiosity about the east, Victoria and Albert understood India from a largely western perspective. The year of rebellion, 1857–8, changed all that.

Get your copy of The English Maharani on Queen Victoria’s 200th birthday!