Roshen Dalal in her book The 108 Upanishads presents a thoroughly researched analysis of the revered philosophical texts, the 108 Upanishads, that form a part of the Vedas. These texts contain the concentrated wisdom extracted from Hinduism over the centuries. Roshen Dalal’s explanations of the core concepts of each Upanishads and her scholarly insights regarding them, makes for one of the most informative reads.

Here we provide some words of wisdom taken from these Upanishads:

In the Katha Upanishad, Yama teaches Nachiketa the concept of the atman. In order to attain a tranquil state of life and transcend death one needs to realize the atman. Yama says that the atman is the master of the chariot which is the body. It is in all living beings and is eternal. Atman is devoid of sound, touch, taste or smell, and never decays. It is only when one realizes that that one can transcend death.

∼

In the Katha Upanishad, Yama explains to Nachiketa the difference between the wise Soul and a fool, saying that a wise Soul would always choose the good, whereas the fool would choose what seems pleasant not thinking of the future. Hence the fool is far away from realizing the atman.

∼

In the Isha Upanishad, verses 9-11 state that neither ignorance nor knowledge lead to the Truth. Avidya (ignorance) and vidya (worldly knowledge), both prove to be inadequate and it is only when one transcends both that one can attain immortality.

∼

In the Isha Upanishad, verses 12-14 explain how both becoming and non-becoming are refutable. It is only when one succeeds in transcending both that the supreme is reachable.

∼

Along with dealing with the unity of god and the world, the Isha Upanishad also talks about the unity of the paths of action and contemplation in one’s life.

∼

In the Prashna Upanishad, a rishi named Pippalada preaches that meditating on even a single letter of Om has many benefits. Meditating on all four syllables of Om together would result in the highest reality.

∼

The Mandukya Upanishad elaborates on the concept of Brahman or the Absolute and the sacred word Om, which also represents Brahman. It further goes on to say that everything is Brahman, including the atman or Self.

∼

It is also stated in the Mandukya Upanishad that just like the objects in a dream are unreal, so are the objects in the waking state too. It is because the atma imagines these objects through its own maya. Thus, the highest truth is the total unreality of the world.

∼

The Adhyatma Upanishad states that Brahman is beyond any conception of beginning and end, actions and all worldly forces. It further says that one should perpetually focus on Brahman and meditate on the true Self withinone’s self. Hence, one should not be attached to the world or identify with the body or the senses.

∼

In the Annapurna Upanishad, Ribhu, a knower of Brahman tells Nidagha how to attain the knowledge of Reality. In order to attain this one should renounce life and make one’s mind detached. A person might or might not act in the worldbut the knower of true reality, can never be an agent or an experiencer of the world.

The 108 Upanishads is a thoroughly researched primer on the Upanishads, philosophical treatises that form a part of the Vedas, the revered Hindu texts.

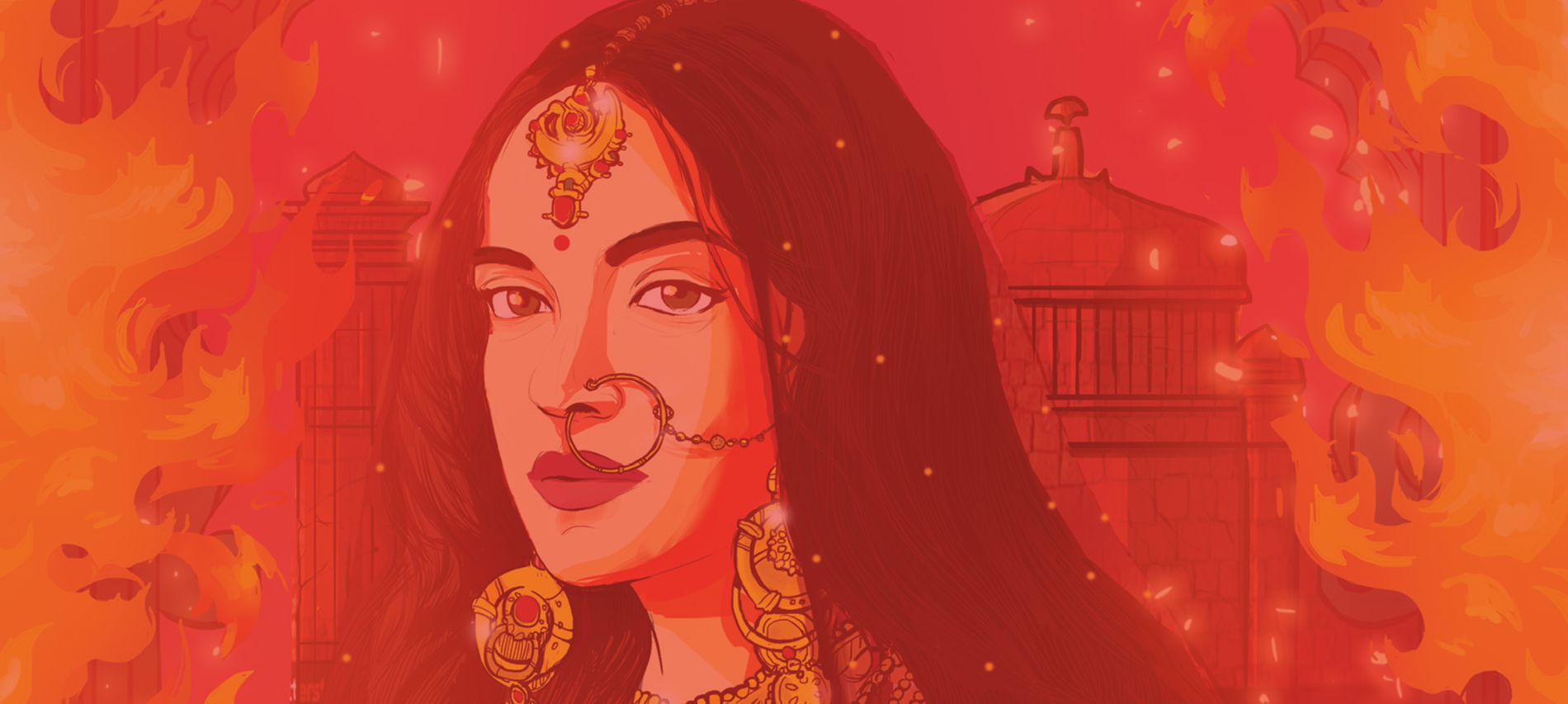

“Veerbhan had thought that he could sweet talk Padmini into accepting the decision… What he saw of her was beyond his wildest imagination. Her eyes, her cheeks, her forehead turned red with indignation. Affronted by his brazen retort, she felt aggressive and resolute in her conviction.”

“Veerbhan had thought that he could sweet talk Padmini into accepting the decision… What he saw of her was beyond his wildest imagination. Her eyes, her cheeks, her forehead turned red with indignation. Affronted by his brazen retort, she felt aggressive and resolute in her conviction.”