Jyotin Goel in Bheem has created a fascinating amalgamation of mythology and adventure in the modern setting. The plot of the book revolves around a deadly threat which has arisen from the ancient battlefields of Lanka and Kurukshetra. Ripping through the vortex of time, Bheem arrives in the twenty-first century to combat this crisis. But to make sure of his failure, a sworn enemy from the past-Ashvatthama-has also journeyed to the present.

Here are some of the characters from the riveting novel:

Don’t wait anymore, pick up Jyotin Goel’s Bheem now!

Tag: Indian literature

How Did the Don Become the Master Baker?

Raja Sen’s The Best Baker in the World opens up the world of cult (and sometimes controversial) films to children and their parents, as Sen’s tribute to Francis Ford Coppola’s The Godfather, comes visually alive with the stunning illustrations done by Vishal K. Bharadwaj. But what is the secret recipe that went into the making of this amazing, one-of-a-kind book?

Raja Sen and Vishal Bharadwaj spill the beans!

Where did the thought of adapting a cult-film into a book for children come from?

Raja: Great stories transcend boundaries. Children routinely read adaptations of classic novels and Shakespeare plays, and I strongly believe cinematic masterpieces are as fundamentally strong as those texts. I thought it would be fascinating to see if a mature, R-rated film can retain its narrative appeal without the ‘adult’ elements — the blood and violence and sex — and if we could still pay tribute to the iconic and memorable aspects of the original film. The characters, the moments, the drama, all of that still remains even if the stakes aren’t fundamentally tied to violence and war. The thing we must remember is that if told right, the popping of a water balloon can feel as momentous in a story as the assassination of a character.

Vishal: When Raja approached me to illustrate the project, two things were set in stone: that these would be ‘adult’ films i.e. ones that only they should watch, as opposed to all-ages classics or PG-13 level movies that a child might be exposed to with the right guidance; and second, that we wouldn’t do a shot-for-shot, beat-by-beat representation of the films. This transformative quality is what really intrigued me about the project.

Why a baker, and not any other profession, for your protagonist who happened to be the head of a mafia in the original?

Raja: More than anything, The Godfather is a film about family — a family business, if you will. It is also a specifically Italian family film, which means food features heavily. Thus I wanted to adapt it around a family business about food, and a bakery seemed both appropriate for the task and appropriately inviting for a children’s setting. As a bonus, my illustrator Vishal Bhardwaj loves cooking and photographing food, and I knew he’d draw mouthwatering pastry.

Vishal: Fairly early on I asked Raja if we could concentrate the setting of the book down to a single street or neighbourhood (the movie takes place across multiple countries and cities), since we were telling an intimate story of families. The term ‘godfather’ denotes a certain protector status, someone you turn to for guidance & comfort. So we thought of similar pillars of a community, the kind who would always be there for you and make you feel better. Also, since I have a penchant for food, a bakery, with all its warmth and the aromas of its fresh baked goods filling the neighbourhood, was the perfect fit.

How difficult was it to dress up The Godfather as a bird who’s a baker?

Vishal: The process took a couple of weeks to go from Brando to bird. Plenty of exploratory sketches, starting with straight renditions of Brando himself, then trying on different animal ‘skins.’ During the research phase I read that Brando thought of Don Corleone as an old bulldog, so he added in the now-famous jowly look to the character. A bulldog version of our Don was tried, but he didn’t vibe with our baker’s character. Finally, after hogs & lions and other beasts, he took the form of a bird, a wise owl. There was the right gentleness to him now, but when Raja saw me draw his wings as delicate arms that manipulated pastry, he asked me to change them to more formidable, warmly enveloping wings almost as huge as the rest of him, and the physical character was complete.

As far as actually dressing him, we moved away from the iconic tuxedo. He is a baker after all, so an apron was appropriate, and rolled up sleeves with a bowtie (he’s still dapper, not sloppy!). I put in a subtle nod to a contemporary chef I like, Mario Batali, who is known for wearing shorts and Crocs sandals under his apron. But because our Don is more old-school (and Raja, like myself, appreciates a good pun), did away with the Crocs and instead gave our big bird a pair of classic wing-tip brogues.

What are the other cinematic masterpieces being retold for children in this series?

Raja: We’re looking at taking on several mature, memorable films and recreating what made them special while setting them in an entirely different (and wholly innocent) world. Next up is a homage to Danny Boyle’s Trainspotting, a highly explicit and wild film about addiction, and one of my favourite films of the 90s. Others on the list include some of the most quotable films of all time, as well as a particularly scandalous one by Stanley Kubrick.

Vishal: I hadn’t seen The Godfather before saying yes to The Best Baker in the World (as it came to be called. For a long time we referred to it as ‘Project Cannoli’). The running joke of-late has been that whatever we end up doing, if it’s a film I haven’t seen before taking the adaptation on, we must be on the right track! Raja has dropped some intriguing names into the hat, from sprawling epic classics to mind-bending modern gems. I’m excited to visually interpret any of these.

Fascinating, isn’t it? Do you still need any more convincing to pick up this marvellous book not just for your little one, but yourself too!

"Where are the words I wrote yesterday?"

Do you remember the last time you took a moment from your busy life to celebrate its little joys?

Ruskin Bond gives us a solution with ‘Words From the Hills’ — a journal that urges you to stop, take a breath, and appreciate the gift of life.

Here’s a short snippet from the book and a prompt for you to pick it up, if you haven’t already!

When I opened my window, the wind came in and snatched my words away. And perhaps that’s where all words go in the end—over the hills and far away, to be lost forever.

A few stray words found their way to the desks of Penguin’s editor Premanka Goswami and design head

Ahlawat Gunjan, and these good souls decided to preserve them for no special reason other than that they were words of love and joy (if not wisdom), and had emanated from my abode in the hills and lent themselves to lyrical watercolours from Ahlawat’s favourite paintbox.

Among other favourite things, he has depicted the rubber plant that flourishes on my bedroom wall. I am not

sure if it wants to make love to me, or simply strangle me. When I returned from a trip to Delhi (or rather Gurgaon,

where everything seems to happen now), I found the rubber plant had spread its tentacles across my pillow, almost as though it was lying in wait for me.

As this is a book of a few words and many colours, I must make this introduction a brief one. The book is really intended for your words, dear reader, and you will find that we have given you the freedom of every page, with space for you to put down your thoughts, feelings and observations before they are carried away by the wind.

This is your book, and the words and decorations are simply there to persuade you to use it.

Ruskin Bond

Ivy Cottage, Landour

August 2017

Inspiring, isn’t it? So grab a pen and get started, because every memory is worth remembering.

The Great Animal Kingdom of Hindu Mythology: ‘Pashu’ — An Excerpt

Hindu mythology not only has some of the most interesting human characters ever, but a huge kingdom of animals too. From fish that save the world to horses that fly higher than birds, every animal in Hindu mythology has a story to tell and a lesson to teach.

Devdutt Pattanaik’s ‘Pashu’ dives into this bizarre, wonderful world of mythological animals and unravels a secret or two about it.

Here’s a snippet from ‘Pashu’ that is sure to make you want to find out more!

Brahma, the creator, had a son called Kashyapa. Kashyapa had many wives who bore him different types of children. Aditi gave birth to the devas—gods who live in the sky. Diti gave birth to the asuras— demons who live under the earth. Kadru gave birth to the nagas, slithering serpents and worms that crawl on trees and on earth. Vinata gave birth to garudas, birds and insects that fly in the air. Sarama gave birth to all the wild creatures with claws and Surabhi gave birth to all the gentle animals with hooves. Timi gave birth to all the fishes and Surasa gave birth to monsters. Thus, all gods, demons, animals and even humans have a common ancestor in Kashyapa. They call him Prajapati, father of all creatures. His story is found in the Puranas, books that are at least two thousand years old.

There are also other theories of how animals came into being. Some can be found in earlier books, while some have never been written but passed down orally by stargazers and storytellers.

Brahma and Shatarupa: The first man, Brahma, saw the first woman, Shatarupa, and fell in love with her. He tried to touch her. She laughed and ran away. He followed her. To avoid getting caught, she turned into a doe. To catch up with her, he turned into a stag. She then became a mare. He became a stallion. She transformed into a cow. He turned into a bull. She became a goose and flew up into the air. He followed her, taking the form of a gander. Every time she took a female form, he took the corresponding male form. This went on for millions of years. Thus, over time, all kinds of beasts came into being, from ants and elephants to dogs and cats. So say the Upanishads, conversations that took place nearly three thousand years ago.

Yogasanas: Shiva, the great yogi, was at peace with himself. In his joy, he assumed many poses, known as asanas. Many of these poses resembled animals. For example, the ustra-asana resembled a camel. When Shiva took this pose, camels came into being. From the matsya-asana, fishes came into being. From the bhujang-asana, snakes came into being. From the salabh-asana, locusts came into being. From the go-mukha-asana, cows came into being. Shiva thus stood in millions of poses, giving rise to millions of different kinds of animals. So says the lore of yogis.

Avatars: From time to time, Vishnu, who resides on the ocean of milk, descends to walk on the earth. He takes the form, or avatar, of different animals when he does so. Sometimes he is a fish, sometimes a turtle, sometimes a wild boar, sometimes a swan . . . In memory of the many forms he took, various animals came into being. So the next time you see a fish, remember that it was once a form of Vishnu. And when you see a swan, remember that, too, was once a form of Vishnu.

Rashi: A cluster of stars is known as a constellation. Ancient rishis divided the sky into twelve equal parts, each occupied by a constellation. The constellations are called zodiacs in English and rashis in Sanskrit. Some of the rashis take the form of animals. There is the Mesha or ram constellation that the sun passes through in early summer. Then there is Mina, the fish; Vrishchika, the scorpion; Simha, the lion; and Vrishabha, the bull. After the sun passes the Makara constellation, whose tail is like a fish and head is like an elephant, the days grow longer and warmer, heralding the approach of summer. After the sun passes the Karka or crab constellation, the days become shorter and colder, indicating the approach of winter. This information comes from Jyotisha Shastra, or the books of astrology. Poets often wonder what came first: the constellations or the animals. Did the design of the stars inspire the gods to create the animals?

Yoni: Many Hindus believe that a being gets a human life only after passing through 84,00,000 animal wombs. Astrologers say that one can find out which was the last animal’s womb or yoni one was born in from one’s time of birth. That yoni determines an aspect of one’s personality. Some of the yonis are: elephant, cow, mare, snake, cat, dog, rat, monkey, tiger, goat, buffalo and deer. Which yoni came first—that of man or that of an animal? Are humans the ancestors of animals or is it the other way around? There is no escaping the fact that we are related to the birds and beasts of the forest. They may be our ancestors or they may be our descendants.

Have more questions on the origins of the mythological animal kingdom? Get your copy of ‘Pashu’ now!

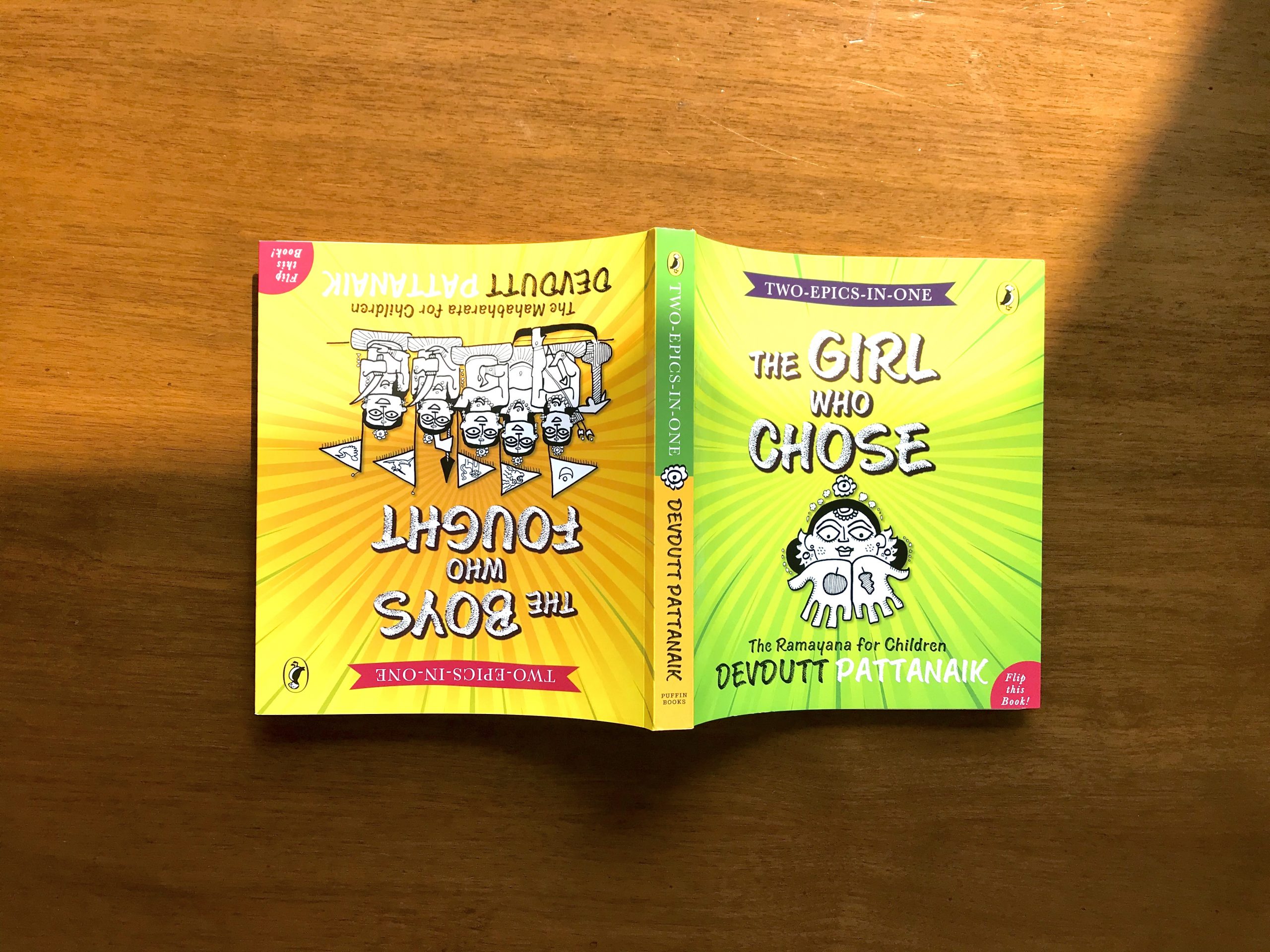

‘The Story of Ravana, Ram or Sita?’: ‘The Girl Who Chose’ — An Excerpt

India’s favourite mythologist Devdutt Pattanaik’s ‘The Girl Who Chose’ brings a fresh perspective to what we have commonly known of the Ramayana — the story of Ram.

However, it has largely gone unnoticed that it was the choices that Sita had made which becomes the pivot for the Ramayana.

Here’s an excerpt from Devdutt Pattanaik’s book telling us why the story of Sita is at the heart of all that happens in the epic.

“Once upon a time, there was a man called Ravana, also known as Paulatsya—being the descendent of Rishi Pulatsya from his mother’s side. He was king of Lanka and ruler of the rakshasas, who tricked a princess called Sita, dragged her out of her house in the forest and made her prisoner in his palace. He was killed by Sita’s husband, Ram, the sun-prince. This story is called the Pulatsya Vadham, or the killing of the descendent of Pulatsya.

The story of Ravana’s killing is part of a longer tale called the Ramayana, which tells the story of Ram from his birth to his death. However, in the din of Ravana’s cruelty and Ram’s valour, something is often overlooked—the story of Sita, the girl who chose.

Valmiki, author of the Ramayana, written over 2000 years ago, tells us how Sita is different from Ram and Ravana. Ravana does not care for other people’s choices, while Ram never makes a choice as, being the eldest son of a royal family, he is always expected to follow the rules. But Sita—she makes five choices. And had Sita not made these choices, the story of Ram would have been very different indeed. That is why Valmiki sometimes refers to the Ramayana as the Sita Charitam, the story of Sita.

Do you know what were the choices that Sita had made? Grab a copy and find out now!

Things You Didn’t Know About ‘Vyasa’ Illustrator Sankha Banerjee

The first in the series that retells the story of the epic Mahabharata, Vyasa sets the stage for the battle of Kurukshetra. This brilliantly illustrated graphic novel is authored by Sibaji Bandopadhyay.

Bringing this epic to life is artist Sankha Banerjee, who enthralls the readers with the many illustrations in the graphic novel.

Here’s taking a sneak peek into the interesting life of Sankha Banerjee.

We bet you’re as dazzled by his art work as we are!

Rusty’s New Room: ‘The Room on the Roof’ — An Excerpt

‘The Room on the Roof’, by Ruskin Bond, is the celebrated writer’s first venture into literature. The heart-warming story of Rusty, a seventeen-year-old orphaned Anglo-Indian boy, looking for a ‘home’ in the charming hills of Dehradun has lived on through decades.

Here is an excerpt from the book on Rusty’s search for a corner he can call his own.

Rusty had never slept well in his guardian’s house, because he had never been tired enough; also his imagination would disturb him. And, since running away, he had slept badly, because he had been cold and hungry. But in Somi’s house he felt safe and a little happy, and slept; he slept the remainder of the day and through the night.

In the morning Somi tipped Rusty out of bed and dragged him to the water tank. Rusty watched Somi strip and stand under the jet of tap water, and shuddered at the prospect of having to the same.

Before removing his shirt, Rusty looked around in embarrassment; no one paid much attention to him, though one of the ayahs, the girl with the bangles, gave him a sly smile; he looked away from the women, threw his shirt on a bush and advanced cautiously to the bathing place.

Somi pulled him under the tap. The water was icy-cold and Rusty gasped with the shock. As soon as he was wet, he sprang off the platform, much to the amusement of Somi and the ayahs.

There was no towel with which to dry himself; he stood on the grass, shivering with cold, wondering whether he should dash back to the house or shiver in the open until the sun dried him. But the girl with the bangles was beside him holding a towel; her eyes were full of mockery, but her smile was friendly.

At the midday meal, which consisted of curry and curd and chapattis, Rusty met Somi’s mother, and liked her.

She was a woman of about thirty-five; she had a few grey hairs at the temples, and her skin—unlike Somi’s—was rough and dry. She dressed simply, in a plain white sari. Her life had been difficult. After the partition of the country, when hate made religion its own, Somi’s family had to leave their home in the Punjab and trek southwards; they had walked hundreds of miles and the mother had carried Somi, who was then six, on her back. Life in India had to be started again, right from the beginning, for they had lost most of their property: the father found work in Delhi, the sisters were married off, and Somi and his mother settled down in Dehra, where the boy attended school.

The mother said: ‘Mister Rusty, you must give Somi a few lessons in spelling and arithmetic. Always, he comes last in class.’

‘Oh, that’s good!’ exclaimed Somi. ‘We’ll have fun, Rusty!’ Then he thumped the table. ‘I have an idea! I know, I think I have a job for you! Remember Kishen, the boy we passed yesterday? Well, his father wants someone to give him private lessons in English.’

‘Teach Kishen?’

‘Yes, it will be easy. I’ll go and see Mr Kapoor and tell him I’ve found a professor of English or something like that, and then you can come and see him. Brother, it is a first-class idea, you are going to be a teacher!’

Rusty felt very dubious about the proposal; he was not sure he could teach English or anything else to the wilful son of a rich man; but he was not in a position to pick and choose. Somi mounted his bicycle and rode off to see Mr Kapoor to secure for Rusty the post of Professor of English. When he returned he seemed pleased with himself, and Rusty’s heart sank with the knowledge that he had got a job.

‘You are to come and see him this evening,’ announced Somi, ‘he will tell you all about it. They want a teacher for Kishen, especially if they don’t have to pay.’ ‘What kind of a job without pay?’ complained Rusty.

‘No pay,’ said Somi, ‘but everything else. Food—and no cooking is better than Punjabi cooking; water—’

‘I should hope so,’ said Rusty.

‘And a room, sir!’ ‘Oh, even a room,’ said Rusty ungratefully, ‘that will be nice.’

‘Anyway,’ said Somi, ‘come and see him, you don’t have to accept.’.

Find out more about Rusty and his delightful adventures today!

Things You Did Not Know About Author and Philanthropist, Sudha Murty

With an ordinary upbringing like most of us, Sudha Murty’s life took extraordinary turns against all odds due to her courage and, determination and will to succeed in life.

Here are a few facts about Sudha Murty that you may have not known before.

Sudha Murty leads with example and shows us that absolutely nothing in life is unachievable, as long as one has the heart to do it.

Forsaken Nests —Perumal Murugan

Perumal Murugan is one of the well-known names of Tamil literature. He has garnered both critical acclaim and commercial success on his writings. Many of his writings have been translated in English and have won accolades. His book ‘Seasons of the Palm’ was shortlisted for the Kiriyama Award in 2005.

Murugan, in this piece tells us what pushed him to become a writer.

My family background could not have been the reason for my becoming a writer. I was a first-generation learner. Both my parents, and their forefathers, were illiterate. After a few years of school, I taught my father how to sign. Signing, for him, meant writing his name. He would write each letter very slowly, leaving a playground of space between two letters. At first he did not know how to pronounce these letters. He took months to learn. He felt it would be beneath the dignity of his school-going sons if he were to remain an illiterate, and so he deeply desired to wipe away that shame with just his signature.

The first time he signed his name was on my report card. That day, his face shone brightly with pride. He never asked about my marks or my ranking. For him, the happiness of signing alone would suffice. My brother would forge my father’s signature, but I did not have that kind of courage. We used to call our father’s handwriting ‘hen scribbles’—like the footprints of hens that pitted the ground when they wandered about, without any discernible form or pattern. To this day, one such signature of my father’s is preserved in my tenth-standard register.

I have never had occasion to regret my being born in an illiterate family. Rather, it was an advantage. I enjoyed absolute freedom as far as my education was concerned. I was free to study; I was also free not to study. No one asked me why I studied Tamil often or told me to study mathematics instead. I alone decided the standard till which I would study. While selecting a field of study of my interest, there was no interference. Nothing can equal the joy one feels at the freedom to make one’s own decisions when young. And because I was born to unlettered parents, I enjoyed the peak of such happiness.

After completing my tenth standard, I myself decided on the branch of study I would pursue in the eleventh standard. Though I had secured more than 80 per cent in the core subjects, I opted to study Tamil literature instead of pursuing science or a technical education. My father willingly accompanied me wherever I wanted to go. If anyone asked why I wasn’t studying something else, he would simply say, ‘It’s his choice.’ This being my ‘educational background’, I cannot ascribe my interest in writing to any of my family members, including my grandparents and parents. I myself struggled and learnt to swim in the great flood. And that happiness still lingers in me today.

How the vocation of writing possessed me can be traced to my childhood. There were not many houses in the place where my family lived. Our household was just one among four on a dry, rain-fed stretch of land called ‘Mettukkaadu’. Unlike in other places, farming in the Kongu region demands more than just a few hours of work and a supervisory visit to the field once in a while. In fact, one had to struggle on the land along with the cattle, night and day. Hence families lived in single tenements on their farms. Along with our grandparents as well as two paternal uncles, we numbered four families in all, and we lived close to each other. Some other houses were also there, scattered in the distance.

I was the youngest boy among the families residing there. Those born after me were all girls. There were no playmates of my age. The difference in ages between the older boys and myself was such that I had to call them anna (elder brother) or mama (uncle). A boy playing with girls would be branded as girly and, in any case, boys looked down upon the games of girls. Hence I had to invent games and play them all by myself. I had to imagine playing and conversing with many people, and I even role-played those other people. I had a lot of uninhabited open space at my disposal. Otherwise I would withdraw into myself like a snail if anyone came near me. I barely spoke in public. I was very quiet, a good boy who did not know of mischief.

But in my lonely private terrain I was an adventurer doing all kinds of things. A circular rock in the middle of the farmlands became my regular playground. When the crops stood high and tall around me, I grew more enthusiastic about my private world. For instance, I very much liked the oyilattom—a folk dance staged during temple festivals. Of course, in the middle of a crowd, my body would freeze up; no force could loosen it. But it would become elastic once I reached the rock. The little sparrows living amid the millet crops and the big birds in the sky would move away, either in awe or in fear. However, one day, while I was dancing in my haven, a tree-climber scaling a palm tree in the vicinity happened to witness my antics. In no time he spread the word about my dancing. After that, I could not show my face in public. From then on, the rock was abandoned. That is just how bashful I was.

An unbridgeable solitude and the fictional world that I created in my private space together have propelled me towards writing. Apart from my textbooks, the magazine Rani was the only book that I got hold of by chance. ‘Kurangu Kusala’ and the children’s segment were the sections I really enjoyed. I started composing verses in line with those in the children’s segment. I sent those songs—rhyming ‘Little, little cat; beautiful cat’—to a radio station a few years later. Most of them found a place in the programme Manimalar broadcast by the Trichy Radio Station. The station would not announce in advance whose songs would be aired so I could never be sure whether my rhymes would be broadcast. And if they were aired, I had no one to share the news with. I did not reveal any of this to others for fear of being ridiculed. But these broadcasts boosted my confidence and eventually helped kindle my desire to publish.

I also had a habit of writing long stories modelled on the children’s series ‘The Secret of the Magical Mountain’ and ‘The Princess of the Hill Country’ that were published in Rani. Tunnels figured prominently in my stories. I loved the image of a shy, fearful person walking through dark tunnels all alone. I would imagine a variety of tunnels; myriad figures would appear as stumbling blocks on the way; those things were dear to my heart.

This was how I came into the world of writing. Even at a young age I could perceive writing to be a way of expressing myself. Still, I have been known as a writer in public only these twenty-five years. If I were to count my published works, there are ten novels, four collections of short stories and four anthologies of poetry. I have compiled a dictionary on the local dialect. Some collections of essays have been published; some others compiled. If all my essays get compiled, then there might be some more books.

One who journeys through my works may happen to identify certain common features. I think most of these would relate to my childhood attitude. When I take a step back and view my work from a distance, I discern that by presenting an observation that has occurred to me, perhaps I could give readers an idea of my childhood. For instance, references to the house are made here and there in my works. But the reader cannot reconstruct the house out of these references. My works don’t have elaborate descriptions of the house, nor are the house and its parts at the centre of the scheme of things. All that my writings needed was the expansive open space. The house as an entity is not suited to fill in the open space. Rather, the house could be seen as an eyesore troubling that space. This attitude can be seen at its peak in my novel Koolamadhari, where the expanse is all pervasive. My childhood idea of the house was only that of a granary—used to store the grains for a year’s requirements. Cooking and sleeping were done outside the house. Even the stove used to be outside the house. A portable charcoal oven was used for cooking during the rainy season. Sleeping took place either in the yard or in the goat pens and the mangers. Though I have become accustomed to the middle class way of life, to this day, I like the open space the most.

Birds do not inhabit nests. They build nests, out of necessity, during the reproductive season. They require the protection of the nests for laying and hatching their eggs and till the nestlings spread their wings to fly. Then the nests are abandoned—forsaken on the trees, fallen on the stones, empty holes left behind after the chicks have grown up. I feel as though my childhood dispositions lie embedded in me in the form of such deserted nests. And it feels right to say that my works encompass such nests.

Translated by: V. Premkumar

Get copies of Seasons Of the Palm, Current Show, and Pyre here.

25 Must Reads On the 70th Anniversary of Partition

India’s freedom from the British rule was stained by the horrors of its partition. The reverberations of the event over the last seventy years have been encapsulated in several books, plays, and other forms of media.

Here is a list of 25 books that capture one of the most defining moment of our history.

Midnight’s Children

Midnight’s Children by Salman Rushdie is an epic novel that opens up with a child being born at midnight on 15th August 1947, just at a time when India is achieving Independence from centuries of foreign British colonial rule. Highlighting the relation between father and son and a nation yet in its nascent stage, it is an enchanting family adventure with lots of human drama and shocking summoning.

Lifting The Veil

Ismat Chughtai in Lifting the Veil explored female sexuality with unparalleled frankness and examined the political and social mores of her time.

Train to India: Memories of Another Bengal

As a young boy, Maloy Krishna Dhar, made the perilous journey to India from the East Pakistan. The partion in Bengal had its share of tragedy, of lives unmade and lost, but it is relatively less chronicled than events in Punjab. Maloy Krishna Dhar’s Train to India is a graphic and moving account of that turbulent and unforgotten era of Bengal History.

The Shadow Lines

As a young boy, Amitav Ghosh’s narrator in The Shadow Lines travels across time through the tales of those around him, traversing the unreliable planes of memory, unmindful of physical, political and chronological borders. Bits and pieces of stories, both half-remembered and imagined, come together in his mind until he arrives at an intricate, interconnected picture of the world where borders and boundaries mean nothing, mere shadow lines that we draw dividing people and nations.

Midnight’s Furies

Nisid Hajari’s Midnight’s Furies: The Deadly Legacy of India’s Partition shows how Partition, which has created such a wide gulf between two countries whose people have so much in common, has given birth to global terrorism and dangerous proliferation.

On a backdrop India’s struggle for independence, Laila, an orphaned daughter of a distinguished Muslim family, fights for her own independence from the claustrophobia of a traditional life. With its beautiful evocation of India, its political insight and unsentimental understanding of the human heart, Sunlight on a Broken Column, first published in 1961, is a classic of Muslim life.

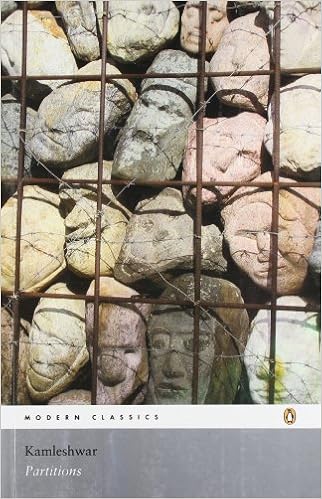

With India’s partition in 1947 as its reference point, the novel presents a limitless canvas against which the most extraordinary trial in the history of mankind runs its course. Kamleshwar’s Kitne Pakistan dared to ask crucial questions about the making and writing of history.

Amritsar to Lahore by Stephen Alter

A sensitive and thoughtful look at the lasting effects of Partition on everyday people, Amritsar to Lahore describes a journey across the contested border between India and Pakistan in 1997, the fiftieth anniversary of Partition. Offering both the perspective of hindsight and a troubling vision of the future, Amritsar to Lahore presents a compelling argument against the impenetrability of boundaries and the tragic legacy of lands divided.

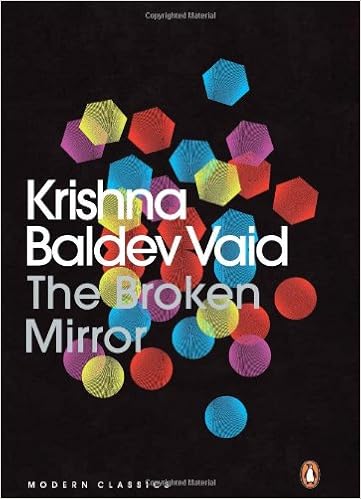

The Broken Mirror by Krishna Baldev Vaid tells the story of Beero and his group of friends against a backdrop of partition of India. Beero’s passage through adolescence is told through a series of eccentric characters. When partition becomes a reality, in a time of terror and carnage, the insane turn out be the only ones sane.

If Partition affected the lives of Sindhi Hindus, it also changed things for the Sindhi Muslims. In Unbordered Memories, Sindhis from India and Pakistan make imaginative entries into each other’s worlds. Many stories in this volume testify to the Sindhi Muslims’ empathy for the world inhabited by the Hindus, and the Indian Sindhis’ solidarity with the turbulence experienced by Pakistani Sindhis.

The Partition of the Indian subcontinent in 1947 left a legacy of hostility and bitterness that has bedevilled relations between India and Pakistan. Reviewing the turbulent history of their past relationship, Radha Kumar analyses the chief obstacles the two countries face in the light of the new opportunities and challenges that the twenty-first century presents.

Bitter Fruit: The Very Best of Saadat Hasan Manto

Manto’s stories were mostly written against the backdrop of the Partition. Bitter Fruit presents the best collection of Manto’s writings, from his short stories, plays and sketches, to portraits of cinema artists, a few pieces on himself. Bitter Fruit includes stories like A Wet Afternoon, The Return, A Believer s Version, Toba Tek Singh, Colder than Ice and many others.

Kingdom’s End: Selected Stories

This collection brings together some of Manto’s finest stories, ranging from his chilling recounting of the horrors of Partition to his portrayal of the underworld. Powerful and deeply moving, these stories remain as relevant today as they were first published.

Mottled Dawn by Saadat Hasan Manto is a collection of stories based on the India-Pakistan partition. The stories written around 1947 put forward the most tragic events in the history of the subcontinent.

Saadat Hasan Manto’s stories are vivid, dangerous and troubling and they slice into the everyday world to reveal its sombre, dark heart. These stories were written from the mid-1930s on, many under the shadow of Partition. No Indian writer since has quite managed to capture the underbelly of Indian life with as much sympathy and colour.

Written by the first President of India, India Divided traces the origins and growth of the Hindu–Muslim conflict, gives the summary of the several schemes for the partition of India which were put forth, and points out the essential ambiguity of the Lahore Resolution. Finally, it concludes that the solution for the Hindu–Muslim issue should be sought in the formation of a secular state, with cultural autonomy for the different groups that make up the nation.

Mr and Mrs Jinnah: The Marriage That Shook India Sheela Reddy in Mr and Mrs Jinnah brings forth the marriage that convulsed the Indian society with a sympathetic, discerning eye. A product of intensive and meticulous research in Delhi, Bombay and Karachi, and based on first-person accounts and sources, Reddy sheds light on how the politics of the time affected the marital life of misunderstood Jinnah and wistful Ruttie.

Sheela Reddy in Mr and Mrs Jinnah brings forth the marriage that convulsed the Indian society with a sympathetic, discerning eye. A product of intensive and meticulous research in Delhi, Bombay and Karachi, and based on first-person accounts and sources, Reddy sheds light on how the politics of the time affected the marital life of misunderstood Jinnah and wistful Ruttie.

A timeless classic about the Partition of India, Tamas is also a chilling reminder of the consequences of religious intolerance and communal prejudice.

Bengal Divided: The Unmaking of a Nation (1905-1971)

In 1905, all of Bengal rose in uproar because the British had partitioned the state. Yet in 1947, the same people insisted on a partition along communal lines. Exploring the roots of alienation of the two communities, Nitish Sengupta peels off the layers of events in this pivotal period in Bengal’s history, casting new light on the roles of figures such as Chittaranjan Das, Subhas Chandra Bose, Nazrul Islam, Fazlul Huq, H.S. Suhrawardy and Shyama Prasad Mukherjee.

In Mukul Kesavan’s Looking Through Glass, a young photographer on a train to Lucknow suddenly finds himself in the deep end of 1942. His hindsight tells him that Partition will destroy this world. And in his desperate struggles to avert the inevitable, we discover, often with an almost unbearable poignancy, how the possibilities in India’s past were squandered, some wantonly, others accidentally.

A collection of two novellas—Regret and Out of Sight, the stories skilfully evoke the long shadow cast by the violence of Partition. While Regret brilliantly recreates a childhood shattered by the Partition of India in 1947, Out of Sight recounts the story of Ismail, who narrowly escaped the carnage of 1947 in his youth. Now, looking back on his life and despairing of the sudden resurgence of sectarian violence in Pakistan.

Memories Of Madness: Stories Of 1947

The tragic legacy of Partition haunts the subcontinent even today. Memories of Madness brings together works by three leading writers who witnessed the insanity of those months—Khushwant Singh, Saadat Hasan Manto, and Bhisham Sahni. As moving as they are disturbing, the stories in this volume are of immense relevance in these times, for they constitute a chilling reminder of the consequences of communal politics.

The Other Side of Silence

Pieced together from oral narratives and testimonies, in many cases from women, children and dalits— marginal voices never heard before— and supplemented by documents, reports, diaries, memoirs and parliamentary records, this is a moving, personal chronicle of Partition that places people, instead of grand politics, at the centre.

The dark legacies of partition have cast a long shadow on the lives of people of India, Pakistan and Bangladesh. The borders that were drawn in 1947, and redrawn in 1971, divided not only nations and histories but also families and friends. The essays in this volume explore new ground in Partition research, looking into areas such as art, literature, migration, and notions of ‘foreignness’ and ‘belonging’.

Remembering Partition: Limited Edition

The Remembering Partition Box Set is a collection of five iconic books which look at the different faces of partition, from the larger political and historical view to the very personal tales of hatred, grief, courage and friendship.

On the 70th anniversary of partition, which book are you picking?